Calendar and plants: May, the flowers’ month

Daniel Climent joins Carles Martín in order to start a series dedicated to the relations between the holiday calendar and the ethnobotany. They start with the month of May, when the ancient considered one of the two seasons in which they divided the year began. Accompanying us to discover traditions and celebrations, such as the May Day flower tree, that go hand in hand with the floral explosion of the countryside at this time of the year.

Mayo florido, por las flores es bendecido (May flowery, by flowers is blessed).

Early European cultures only considered two climatic seasons: that of “good weather” (which the Romans called vernum tempus or aestivum tempus) and that of “bad weather” (hibernum tempus). Both began forty days after the solar ephemeris, a time considered transitional as well as communicational between two worlds, the earthly of living nature and the underworld of suspended nature.

The hibernum tempus began on November 1 (samhain, for the Celts), forty days after the autumn equinox; it represented the withdrawal of the protective deities’ support. Therefore, we entered a time of nature’s world death. We have inherited and Christianized it through the consecutive All Saints Day and All Souls Day holidays, nowadays transformed into a Halloween masquerade, with such a light and lay character that destroys the holiday’s sense.

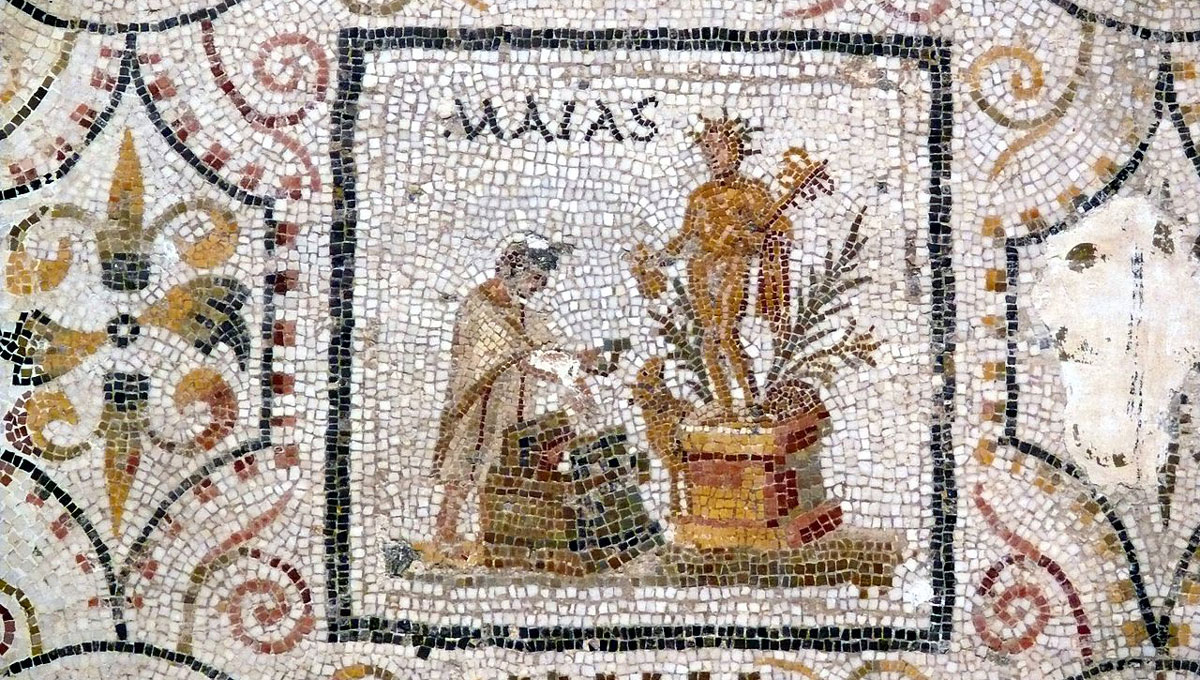

Fragment of a Roman mosaic with an image corresponding to the month of May. Sousse Archaeological Museum, Tunisia. / Ad Meskens – Wikimedia

As for the vernum tempus and aestivum tempus, they were, depending on the latitude, the two possible entrances to the good weather season. One was on February 2, forty days after the winter solstice. The saying goes: “Si per la Candelera flora, l’hivern ja està fora; i si no flora, ni dins ni fora” (If the wavyleaf mullein blooms the winter is out, if it doesn’t the winter is neither in nor out). And the other one was, especially, on May 1, forty days after the spring equinox. A floral and joyful time but also conducive to communication between the worlds of the dead and the living, as we will see.

The start of the good weather season in the northern European world

The night between April 30th and May 1st the Celts celebrated Betlane, the entrance to the good weather season. Equivalent festivities were held in the Germanic world, Walpurgis (Walpurgisnacht), and Scandinavian, Valburg (Valborgsmässoafton). In fact, the special celebrations list for this same reason is so much longer and goes from the northern to the southern Europe in that night’s traffic: in Estonia, the night of Volbriöö is followed by the big festival of Kevadpüha; in Finland Vappu; in northern Italy (ancient Cisalpine Gaul) Calendimaggio; also in northern and Celtic Portugal, and in Galicia, Maias and Hueso Maios, respectively; in Wales, the night of Noes Calan Haf is paired with the feast of Calan Nunca or Calan Haf; and in Greece Πρωτομαγιά (protomàgia in modern Greek). Ending with the English May Day celebration, which we must not confuse with he international emergency code as a demand for help, the triple mayday (which, in fact, comes from the French m’aider, “help me”).

On April 30, the cattle were uncovered and allowed to leave the houses where the bad season had passed, so that it could graze. During the night, bonfires were lit to frighten predators and the next morning, on May 1, floral, dendrolateric cults, and sacred trees veneration rituals were performed. Many of those ancient European peoples, some of whom would move south centuries later, renewed the veneration of certain totemic trees on that day. They adorned the paths’ crosses with flowers and the spouses’ heads with garlands in case of wedding celebrations.

Movie frame from The War Lord, 1965. Where a wedding is celebrated with ancient pagan rituals in 11th century Normandy.

We shouldn’t forget that the Walpurgies night was also a time when the deceased communicated with the earthly world. Times of witches and enchantments, similar to the October 30 to November 1 transit, Samhaim. Floral and vegetable rituals were used as spells against afterlife spirits.

In a similar way, the ancient Romans celebrated the Floralia in late April and early May, about which we will talk in a next article. Nowadays, there still are floral gifts in France, where give away small lily of the valley bouquets (Convallaria majalis) is something traditional the first day of May. The scientific name Convallaria majalis comes to say “lily (lilium convallium) of the valleys (place where it blooms) by may” (the suffix -aria, -ariae indicates relationship in broad sense). It is considered the Sweden (liljekonvalj) and Serbian (Ђурђевак , Đurđevak) national flower, and also the Finland one, where is called kielo, which is also a traditional feminine name.

Despite the dramatic conditions we are living in with the COVID-19, the first of May has been remembered in France with the corresponding floral symbol, the lily of the valley. / www.thegoodgoods.fr

The staggered arrangement of these Maiglöckchen flowers (“small May bells”, in German) made this plant one of the preferred to decorate the Virgin Mary of May altars in the Central European monasteries, as a symbol of the desired ascension related to the Month of Mary prayers.

The plant has become Dior’s house fetish flower (fashion, jewelry, perfumery) and symbolizes the first of May date itself, as can be seen from the Franz Xaver Winterhalter work (1805–1873), chamber painter of the nineteenth-century European courts. In The first of May 1851 painting, Prince Arthur, son of Queen Victoria and Prince Eduard, offer to the Duke of Wellington a lily of the valley flower. Here, the bouquet has a double meaning: it indicates the prince’s first birthday, and also the date on which the London Crystal Palace was inaugurated for the Great Exhibition (in the background, on the left), First Industrial Revolution expository apotheosis. A work designed and directed by a gardener and landscaper, Joseph Paxton (1803-1865), an innovator in the use of laminated glass and iron from easy-to-fit prefabricated modules.

On the left, The first of May 1851 painting by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-1873) showing the prince offering the Duke of Wellington a lily of the valley. / Wikipedia. On the right, more detailed picture of the lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis). / H. Zell – Wikipedia

As an amatory plant, in Germany, the Maiglöckchen was given “to melt girls’ hearts”. As the poet Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) warned, making a pun between metaphor and reality, this flower “bricht das Eis des Winters und der Herzen” (breaks the ice of both the winter and the heart). Despite its beauty, aroma, and symbolic value, we must not underestimate the lily of the valley’s toxic character. The glycosides it contains (convalarine, convalamarine and convalatoxin) can cause cardiac and digestive disorders (nausea and vomiting), although, if appropriate measures are taken in time, poisoning does not necessarily end in death.

And its precisely its toxicity that has given the lily of the valley an exceptional role in two of the most successful television series, Breaking Bad and Outlander, in which the protagonists’ ethnobotanical and toxicological knowledge decisively contribute to the plot.

In the first case, the organic chemist Walter White manages to assassinate his boss and rival Gus Fring using a lily of the valley’s extraction. The idea comes to him relating the poisoning of the son of his friend’s girlfriend Jesse by the lily of the valley’s presence in a garden pot.

A frame of one Breaking Bad series chapter, in which the protagonist realizes that the lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis) can help him to get rid of his enemy. / Breaking Bad Fandom

On the other hand, the fact that the lily of the valley’s leaf is easily confused with that of the edible wild garlic or ramsons (Allium ursinum) can induce eating the bulb. This seems to be the case narrated in the third episode of the British first season series Outlander. The nurse Claire saves a child who has been poisoned by supplying him with another plant as an antidote, belladonna (Atropa belladonna, rich in cardiotonic atropine), apart from fighting the parish rector who attributes the child’s illness to divine punishment.

The tree of May flowers

Some deciduous forest peoples (Celtic, Germanic, Basque, Slavic) included dendrological patterns and decorated road crosses with flower garlands. In the Celts’ case, for whom certain trees were associated with the lunar calendar months, the 1 to 25 of May period corresponded to the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), a little tree also known as one-seed hawthorn, single-seeded hawthorn, and more spectacularly flowery and overflowing with youthful joy at that time of the year.

On the left, hawthorn’s photo (Crataegus monogyna). / Emili Laguna. On the right, detail photo. / Daniel Climent

The phonological relationship between the flowering and the month of May has been recorded in phytonyms such as the French bois de mai, the Dutch meidoorn, or the English may, maytree, maybush, maythorn, mayblossom o mayflower. And not only in phytonyms but also in popular sayings such as the Northern Ireland one: “ne’er cast a clout ‘til May is out”; or the French one: “dejà est passé l’hiver, que l’aubépine fleurit et que la rose s’épanuit” (the winter is over because the hawthorn has blossomed and so has the rose bush).

That bond inspired poems such as Court of Love, in which the English lyric initiator, Geoffrey Chaucer (1340-1400), recommended the entire entourage to go catch flouris fred, and branche and bloome (fresh flowers, branches, and buds) on the first of May.

Amongst the many buds proclaiming May, decking the fields in holiday array, striving who shall surpass in bravery. Mark the fair blooming of the Hawthorn tree, who finely clothed in a robe of white, Feeds full the wanton eye with May’s delight. Extracted from Arboretum et fruticetum britannicum, John Claudius Loudon (1838).

The Catalan phytonym santperemàrtir, in turn, is a metonym associating the plant’s name with the day of its use. In the Cadí pre-Pyrenean mountain range it was customary to go out into the field scattering hawthorn garlands in order to favor the harvests during the May 1 eve (April 30, Sant Pere Mártir’s feast). On the same day, in England, the cobwebs of gardens and stables were cleaned with hawthorn branches and, in northeast France, flowering branches were hung to prevent the access of spiders called sorcières (witches).

That apotropaic power of prevention against malefic influences was already attributed to it in ancient Rome. To the point that the poet Ovidi (43 a. C.-17 d. C.) wrote that “[the Carna nymph] deposited a hawthorn branch […] under the small window that illuminated the room [of the unborn child] and thereafter the birds (witches or vampires) respected the cradle” (Fasti VI, pp. 165-169).

It allows, facilitates, and encourages us to study how humans have not only used plants throughout history, but also how we have projected our emotions, desires, and fears onto them.

In many Spanish peoples, the holidays taking place in the month of May were celebrated with rituals where the tree had a prominent role. In the image, La cucaña painting, by Francisco de Goya (1746-1828). / Wikipedia

Christianity, observing that dendrological and floral cults of the first of May were very difficult to banish –even when people had left the wooded and wild environments– opted to Christianize and absorb them, make them his own. Thus, in the hawthorn case, the so-called Glastonbury thorn, a variety that blooms twice a year (biflora) –once in winter– was venerated in England. In the ad hoc legend, it was considered that this tree located in Somerset (south-west of England) was the regrowth of Joseph of Arimathea’s cane –the one he carried during his escape from persecution to England, unleashed against Christians after Jesus’ resurrection. The legend is told in the Herbari. Viure amb les plantes book, by Daniel Climent and Ferran Zurriaga (Universitat de València publication, 2012).

But, as the inspired novelist Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) would say, this would already be the reason for another story. Don’t suffer, we’ll deal with it in the next chapter.