Conserving the Little Dragon of the Sierra de Gádor

Exploring nearby caves, searching for new populations and assessing its reproductive capacity and genetic diversity are the main topics of the latest research project conducted by the Botanical Garden of the University of València in order to save this endangered rupicolous species. This Mediterranean endemism only grows in a specific area in the Sierra de Gádor. What are their main threats and what can be done to prevent its extinction? Jaime Güemes, director of the Botanical Garden, and Anna Nebot, botanists, will tell us everything about it in this article.

Gadoria falukei, one of the most endangered plants in Europe, grows in some balms located in the lower part of the Sierra de Gádor, close to the greenhouses covering the Campo de Dalías area. This “sea of plastic” shocked the astronauts aboard the International Space Station because it was the only human built structure visible from the station, orbiting 249 miles from Earth, without using any observation devices. But our plant grows far from the greenhouses and the influence of human activity. On the contrary, you can only find it in the first rocky walls of the South face of the Sierra. There are no nearby paths, so that is why the plant had been under the radar for the scientific community until the last decade. Only shepherds and their cattle used to go up there to sleep, protected by the balm’s walls and the dry stone walls of the sheepfolds. They slept close to the plants that were actually growing over their heads.

This endemic species from the mountains of Almería was discovered just four years ago by Francisco Rodríguez (also known as “Faluke”), a member of the Almería Naturalist Group. It was officially described in 2017 by Jaime Güemes, who at the time was the curator of the Botanical Garden, and Juan Mota, professor at the University of Almería. During the last few years, researchers have conducted a huge taxonomic and phylogenetic study allowing them to include this new species in an also new genus. They have also concluded that the closest species is the Asarina procumbens Mill., located in the Pyrenees, and that the new species could be 7 million years old.

Nowadays, thanks to the Let’s save Gadoria falukei, a Critically Endangered and very singular plant species recently discovered in southern Europe project, funded by the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, we can keep researching to find out more about the plants’ situation of endangerment, genetic diversity and reproductive biology. There is only one known population of Gadoria falukei in the world, with only a hundred individuals.

Gadoria falukei. Picture by Anna Nebot.

The main goal of the project is to set the bases to achieve the conservation of what may be the most endangered European floral species. That is why we have visited the town and the Sierra de Gádor four times. We wanted to count the alive individuals and search for new populations in the caves and balms to reduce the level of endangerment. We also wanted to know more about its reproductive capacity and genetic diversity.

Field work

Since 2013, we have been creating an annual census of the known population, so right now we have data from the last 10 years that help us see their evolution and calculate their survival or extinction rates. Monitoring populations allows us to know the species demographic evolution and foresee changes in the number of individuals. That is why this is an essential value to design any conservation strategy. The rupicolous habitat of the little dragon of the Sierra de Gádor, a plant that grows on cracks located on vertical walls and high protruding rocks, makes the data collection for the census quite difficult. That is why we have used telescopes, binoculars, cameras and drones. We have detail and panoramic pictures of the balms and walls where we found the plant. Year after year, we take new pictures in order to determine whether or not there are new individuals, identify the plants that have died and observe the evolution of the ones we have previously registered in the census (changes in size, blooming, fructification…).

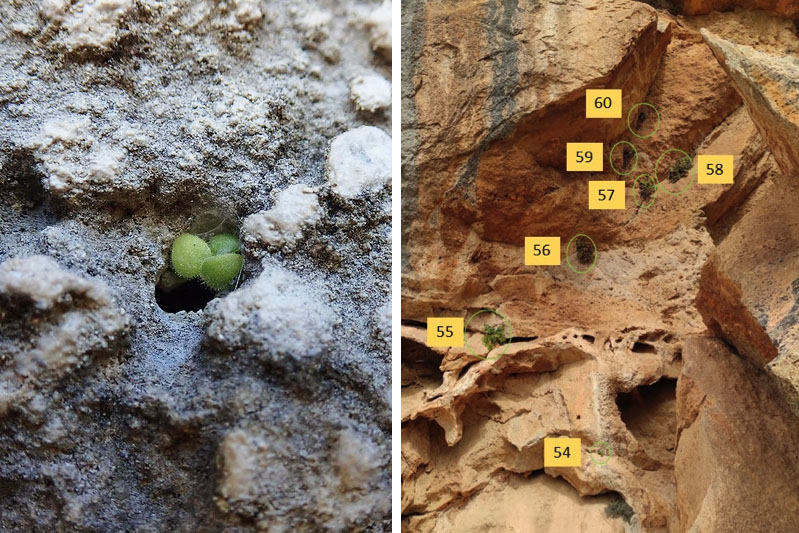

On the left, a new individual growing between the cracks of a rocky wall. On the right, detail of a wall with the distribution of Gadoria falukei individuals. Pictures by Anna Nebot.

We collect data for the census during the blooming period (from April to June), because the yellow flowers stand out in the walls and the plants are easier to identify. It is also easier to set them apart from other species living in the same area that have similar habit and leaf morphology. That is the case of the Lafuentea rotundifolia, another endemism from the south-east of the peninsula, but even rarer and distributed from Málaga until Alicante, that grows next to the known population of Gadoria falukei.

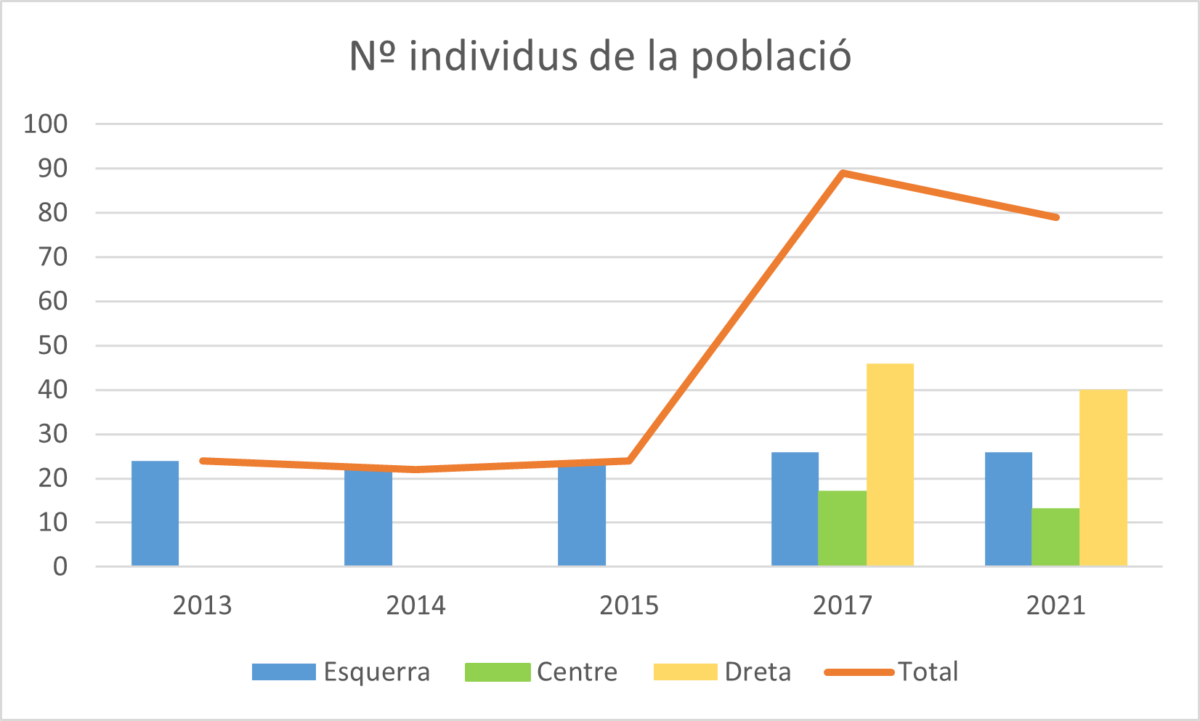

The observations from the last 9 years have allowed us to discover, in 2017, two new subpopulations growing close to the original one, with no apparent reproductive isolation. This was a substantial increase of the total number of individuals. Nevertheless, a deep analysis of the evolution of the census shows the existence of a certain population dynamic (dead individuals are replaced by new ones) and certain demographic stability.

Bar chart showing the distribution of Gadoria falukei individuals in the 3 subpopulations that have been identified through the years. The orange line shows the total number of individuals

The original subpopulation has 25 plants (since 2013, we have always counted between 22 and 26 individuals), while the subpopulations found in 2017 have around 55 individuals. Based on our observations, in 2021, the species’ world population was put at 79 individuals, 35 of them were adults capable of blooming and producing seeds.

During the making of the census, we also collected leaves from all the plants that were accessible to conduct a molecular study in order to gather data about the species’ genetic diversity. We also wanted to find out if there was a genetic difference between subpopulations. Genetic impoverishment may be responsible for the species’ lack of endurance and risk of endangerment. Preliminary studies confirmed the expected genetic homogeneity among all the individuals, something typical of small populations with a limited distribution. Perhaps, in the future, with the use of more specific molecular markers, we will be able to find some genetic diversity in the species and some difference between the known subpopulations.

Individual of Gadoria falukei during the reproductive biology experiments. Picture by Anna Nebot.

Knowing a species’ reproductive capacity is key to assess the threat level and to design any conservation programme. For this reason, during our visits this year, we also conducted different trials to provide us with data on the behavior and reproductive success of the adult specimens. We isolated flowers inside very fine gauze bags to prevent access by pollinators and to estimate the autogamy capacity (existence of effective self-pollination) of the flowers. Other flowers were manually pollinated, depositing on their stigma, with the help of tweezers and brushes, pollen from distant flowers, thus reducing inbreeding. Finally, the fruit and seed production of these experiments was compared with that of unmanipulated flowers. We also estimated their quality (weight) and viability (germination capacity).

With all these data in hand, we have found that Gadoria falukei is able to produce seeds without pollen exchange between flowers, that there is no lack of pollinators in the population, that there is no inbreeding depression (loss of quality or viability of seeds produced by autogamy) and that the seeds have a high germination capacity. Therefore, the reproductive process is not jeopardising the survival of the species.

Ex situ conservation

The difficulty of working in the natural habitat with a plant like this, the opportunity to establish a seed orchard (to produce and collect large quantities of seeds) and the need to obtain specimens to be able to propose in the future actions to reinforce the population with new individuals led us to cultivate hundreds of plants outside their habitat, in the Botanical Garden of the University of Valencia. We collected seeds from all accessible plants in the natural population, approximately 20% of those observed, and planted a portion to produce new plants in the Garden’s nursery.

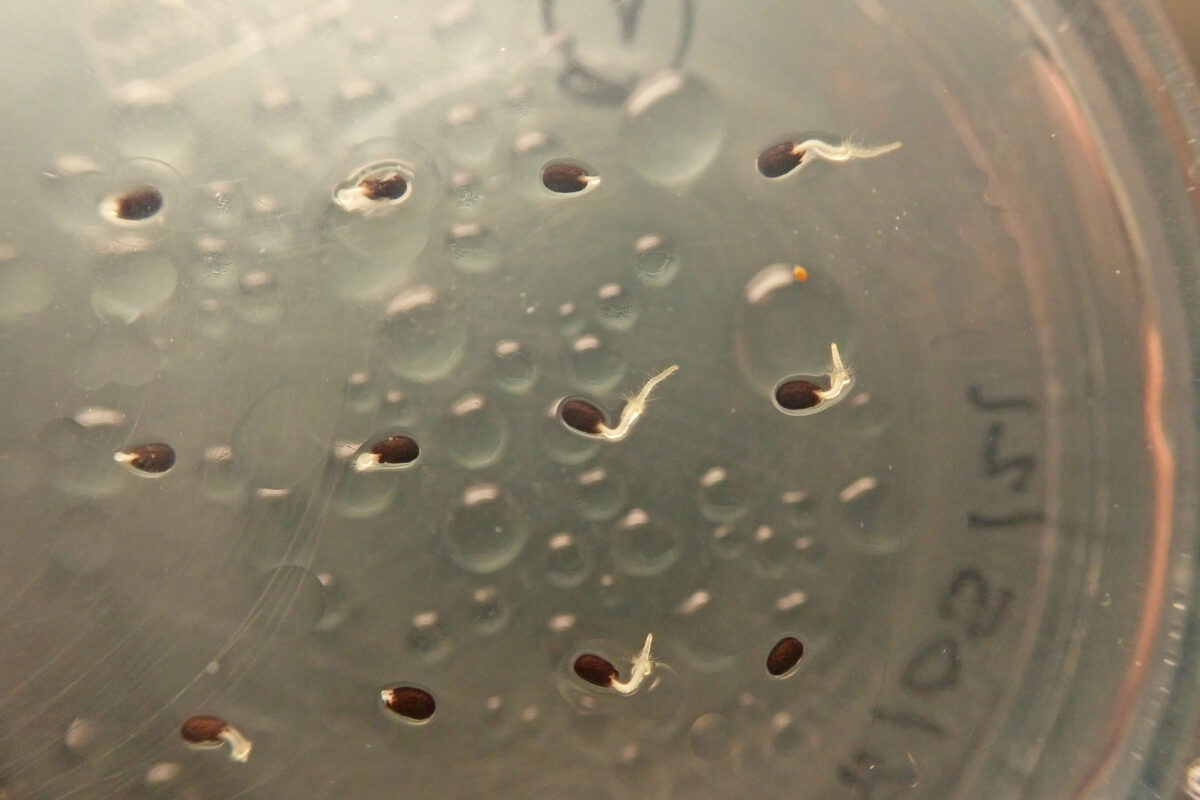

Thanks to these plants, which bloomed 5-6 months after sowing, we have been able to increase the number of reproductive trials, repeating ex situ the same ones we did in the field, as well as others that increased our knowledge of the reproductive biology of the plant. We have obtained thousands of viable seeds, with a germination capacity over 90%, both in laboratory conditions) in a germination chamber at a temperature of 20° C and alternating 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness) and in the nursery seedbed, with temperatures and light typical of January and February.

Both the seeds collected from the natural population, during the reproductive studies, and those produced in the Botanical’s nursery were conserved in the Garden’s Germplasm Bank. Always keeping the seeds separated by individuals, in case material from a specific plant is needed in the future, they were placed in hermetically sealed capsules at a temperature of -20° C, after previous dehydration and cleaning treatments. This way, Gadoria falukei has been conserved ex situ and we have abundant reproductive material to carry out new trials and to propose new conservation actions in the natural environment, such as the reinforcement of the known population or the creation of new populations in suitable places in the Sierra de Gádor.

New technologies to help with the conservation of the species

Back in the field, we used an analysis with predictive models of species distribution to try to locate new populations. These models are based on statistical procedures of climatic, edaphic, geological, geographic and cartographic data analysis. Thus, the environmental variables of the known populations are compared with those occurring at each location in the Sierra. The model suggests towns or areas of high environmental similarity to the areas where we found the original populations and where new populations of the species under study can potentially be found. This type of model has greatly helped in recent years to find new populations of endangered and sparsely distributed species, contributing to the reevaluation of their level of threat.

The Sierra de Gádor is a large mountainous massif with a surface area of more than 203,600 acres and thousands of caves and grottoes similar to those where the plant lives. The application of the predictive model to the case of the little dragon of Gádor pointed out more than one hundred potential points in the Sierra where there are caves with similar characteristics to those where the known population grows. During 2021, we visited more than 30 of the pointed sites, travelled more than 124 miles on forest tracks and walked for many hours on the steep slopes of the Sierra, crossing dense thickets and observing with binoculars the indicated caves and walls. Unfortunately, we have not been able to find any new population so far.

In the spring of 2022, we will go back to the Sierra with the model updated, it will include all the new information about the absence of Gadoria falukei in the visited sites. We hope this will improve its predictions and increase the probability of getting the automatically chosen towns right. We also want to go back to the Sierra with drones that will facilitate the visual approach to the rocks and the access to the high and hidden parts of the walls. In addition, they will allow us to capture panoramic images that we will later treat with image analysis systems to detect the presence of the species among the plants that live in the cracks of the walls.

What do we know by now about the little dragon of the Sierra de Gádor?

After having conducted these studies, we have obtained really important information. We have confirmed that Gadoria falukei is a very rare species and is critically endangered. There are only 80 individuals in an area of about 21,530 sq. ft. In addition, the species may be genetically impoverished because it shows very low genetic diversity and, so far, we have no evidence of any other existing population.

Seeds of Gadoria falukei germinating during the viability tests. Picture by Anna Nebot.

We also know that the species is capable of producing viable seeds without the need of pollinators and that the walls where it grows have few crevices in which to establish new plants. But, thanks to the large number of seeds produced each year by adult individuals (about 3,000 seeds per individual) and the high germination rate, we have been able to observe seedlings and new young plants, which shows that it has some population dynamics.

Their main threat is the action of herbivores on accessible plants, which limits the expansion of the species in the lower part of the caves, and the effect of trampling on the seeds that, without having found a crack in the stone, fall to a ground frequented by goats and sheep. This could be corrected in the short term by limiting the access of livestock to the shelters. In general, the reduction of livestock activity in the area could have a positive impact on the population of the little dragon of Gádor. What we do not know, for the moment, is how climate change (i.e. reduced rainfall and higher temperatures) will affect a species that lives in one of the sub-desert areas of Europe and has a very low genetic diversity, which could make it difficult to adapt to future environmental changes.

Conservation measures

Although the conservation of the seeds of Gadoria falukei in the germplasm banks of different Spanish institutions reduces the risk of extinction, its survival in the wild is still in danger. Therefore, it is necessary and urgent to implement different in situ conservation measures that should include, in the first place, its legal protection. Consequently, it should be included in the Catalogues of Threatened Species of the National and Andalusian Autonomous Government. Also, the area of protection of the Special Area of Conservation of the Sierras de Gádor and Enix should be extended to the Peñón de Bernal, a site of great botanical, geological and landscape interest, where the population of Gadoria falukei is found. In addition, herbivores should have limited access to the points of the cave with the highest density of plants to see the real effect of the absence of herbivory and livestock presence.

Finally, it is still necessary to monitor the evolution of the population, maintaining the annual census and the search for new populations with predictive models that are increasingly accurate thanks to the help of drones. We will continue to work on this task in the following years to know the real risk of extinction of the species due to its own evolutionary characteristics.

Research team

This research work has been made possible thanks to the support of the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and the collaboration of research teams from the Andalusian Network of Botanical Gardens (Vicky Hedwig), the University of Almería (Juan Mota, Esteban Salmerón, Fabián Martínez Hernández, Antonio Mendoza), the Polytechnic University of Madrid (Elena Carrió) and the University of Valencia (Anna Nebot, Isabel Martínez Nieto, Javier Fabado, Elena Estrelles, Jaime Güemes).

Enllaços

- Casas, A. (2017) Entrevista a Jaime Güemes. Mètode - Güemes, J. & Mota, J. (2017) Gadoria (Antirrhineae, Plantaginaceae): A new genus, endemic from Sierra de Gádor, Almería, Spain. Phytotaxa 298: 201-221. - Nebot, A., Hedwig V. & Güemes, J. (2021) Estudios in situ y ex situ de Gadoria falukei Güemes & Mota, especie en Peligro Crítico, endémica de la Sierra de Gádor (Almería, España). I Congreso Español de Botánica, Toledo (España). - Nebot, A., Martínez-Nieto, MI., Fabado, J. & Güemes, J. (2021) In situ and ex situ studies to improve the conservation status of critically endangered endemic plants. 3rd Mediterranean Plant Conservation Week, Chania (Crete). - Sen Nag, O. (2020) The Miracle Bloom of a Rare Mountain Flower Brings Hope in Challenging Times. - YouTube HDL Investigadores botánicos descubren en Almería un nuevo género de plantas: la Gadoria falukei.