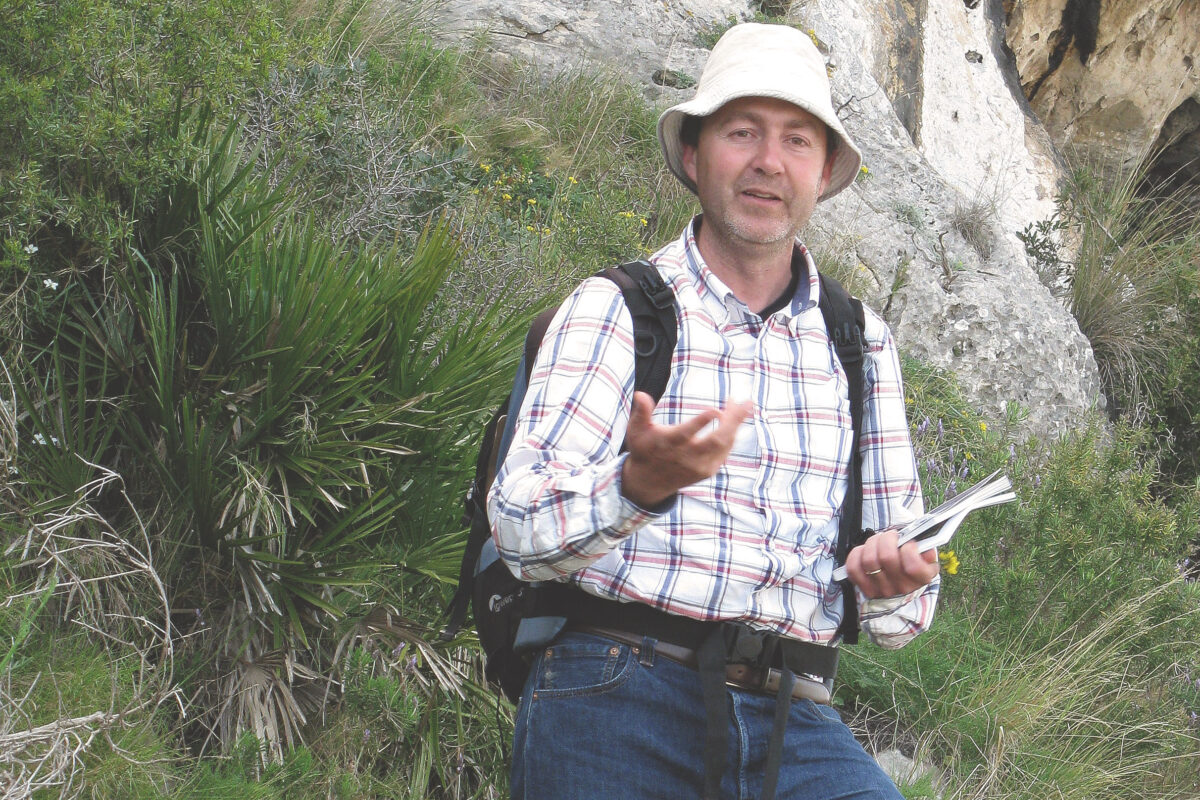

Botanist of the month: Jaume X. Soler

Our land, its landscape and plants seduced botanist Jaume X. Soler, born in the Marina Alta region, from a very young age. This passion soon turned into a vocational profession. He has worked in many different fields such as agriculture, forest management, environmental restoration, preservation, cartography or scientific dissemination. Quite an eclectic career marked by his experience in viticultural research and production. This kind of knowledge allows him to spend his time doing what he likes the most: floristics, taxonomy and sharing his expertise with other citizens.

What attracted you to Botany?

From a very young age, I remember being interested in discovering my surroundings. I guess it was just this curiosity we all have when we are children. But I actually started finding out more and more about plants and getting in touch with nature because my dad and his friends used to take me hunting. I was roughly ten years old and my dad had a friend called Juan “Platero” who knew a lot about plants. So, everyday, he taught me something: “this plant helps the kidney, this one is good for your tummy”. This experience with my dad, my first contact with nature, made me want to learn more about plants. I figure those were the first steps of my journey as a botanist.

I also got a very special present on my 13th birthday: a guide of plants by Félix Muñoz-Garmendia, who I got the pleasure to meet during my first visit to the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid in 1992. Actually, when I was 14, I remember being asked “What do you want to be when you grow up?” and I answered: “A botanist”.

From those days on, my life has been dedicated to learn about the plants that surround me. I wanted to understand why some species grow and others don’t, how did this landscape we are looking at got to be the way it is and how can we use all this knowledge to help our society. I can’t understand why, nowadays, we turn our backs on plants and their diversity, when we are surrounded by them, in gardens, farms or mountains. Not very long ago, everybody knew the names and properties of some basic plants, because they were used in daily life. But that has changed. It is also important to say that, as I grew older, I got to love Botany even more when I discovered the wide array of plants growing in the Iberian Peninsula, both native and farmed. And lately, the plants used in gardening.

Could you tell us a little bit about you professional career?

My youth was riddled of family problems that defined my personality, but I managed to graduate and I eventually got a degree in Biology, with a specialisation in Botany, from the University of Valencia. I remember we were only eleven students in that field, something that was clearly a sign of “decadence”.But sometimes there is a silver lining: I was lucky enough to be one of the last students of the only doctorate programme in Spain exclusively dedicated to Botany.

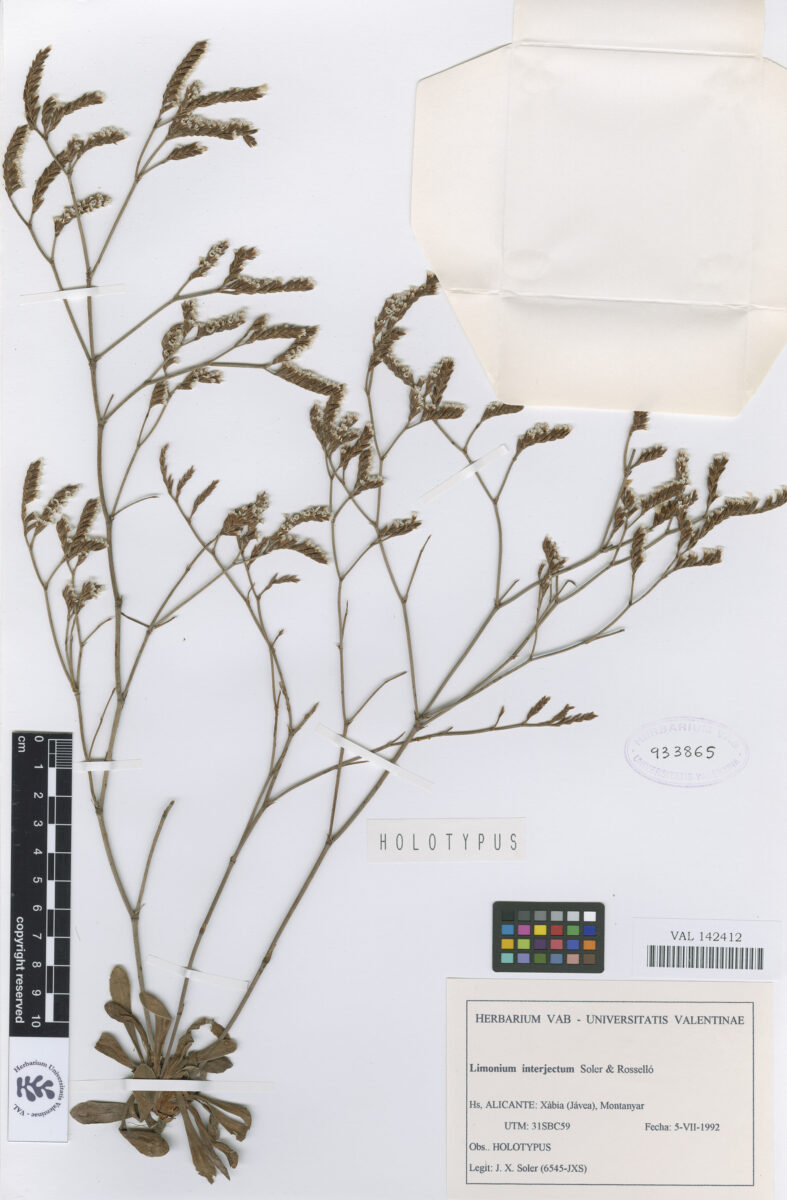

In 2000, I finished my PhD in Botany in the Department of Natural Products, Plant Biology and Edaphology at the Faculty of Pharmacy of the University of Barcelona, although I still have to defend my thesis. I think I was lucky, because I am an “old school” floristic botanist who can understand most of the current biosystematic, and I am very proud of it. I have worked in different botanical and agricultural research fields and I have managed to publish 32 scientific articles. Personally, I think my highest achievement has been the identification of three new plants: Limonium ejulabilis, Roselló, Mus & Soler, Limonium interjectum Soler & Roselló, Ophrys x castroviejoi Serra & J.X. Soler.

Holotypus of Limonium interjectum. Picture: Herbarium of the Botanical Garden of the University of Valencia.

In 2005, I founded my own company (Serveis Agroambientals Marina Alta S.L.) focused on environmental and agricultural management. We do all kinds of work connected with the territory, specially in the agriculture, forest management, and scientific dissemination fields. In 2011, due to bureaucracy, I founded my second company (Botanica Mediterranea S.L.) also dedicated to research activities and the world of plants, but also to publishing scientific dissemination books. To this day, and always in collaboration with my colleague and friend Lluís Serra, I have published six books (El paisatge vegetal de Teulada; Guía botànica del Parc Natural del Montgó; Plantas de Interés de Teulada. Una herramienta para la ordenación del territorio; Flora del Parc Natural de la Font Roja; Patrimoni vegetal a Xàbia; Manual d’identificació dels hàbitats protegits a la Comunitat Valenciana) and I have collaborated in at least ten more.

Publication of ‘Plantas de Interés de Teulada. Una herramienta para la ordenación del territorio‘ by Jaume X. Soler, Lluís Serra, Antonio Hurtado and Marisa Bertomeu.

Finally, I would like to point out that, in the last years (2009/2019), I have been working on and off in the habitat cartography of the Valencian Autonomous Region for the Valencian government, together with my good friend Carles Fabregat.

What exactly do you do at work?

My main job is quite diverse, because I have two companies fully dedicated to mostly everything that has to do with plants, agriculture, forest management, environmental restoration, scientific dissemination, scientific studies, conservation, etc. Nowadays, I invest a lot of time on viticulture. In order to produce quality wines, we do research, give advice and generally work for different wineries and projects located in the Marina Alta region, so they can make wines adapted to our natural conditions. I think viticulture can be very attractive for a “non public worker” botanist. You could be in charge of many acres, but your work will only last 6 to 8 months. More land, more workers, but always the same amount of months, so you are left, at least, with four months you can devote exclusively to botany.

Over the last few years, I have spent my free time doing different botany works that I wanted, especially all kinds of scientific dissemination, usually together with my good friend and colleague Lluís Serra. I completed some forest restoration projects as well as others on habitat maintenance that meant a lot to me and, I hope, to society. But lately I’ve been spending more time doing floristics and taxonomy, just for the love of it. I study many groups of plants from the Iberian Peninsula just because I enjoy it, not because I have a goal or a project or I want to extend my CV. And, from time to time, I get to publish something.

In the centre, Oprhys x castroviejoi between its parentals O. speculum and O. scolopax. Picture by Jaume X. Soler.

I have to admit these botany works are the most relaxing and calming moments I have in my life, and it is totally worth it. The results are great when you don’t feel the pressure of having to get immediate and required results.

Are you proud of any project in particular?

During my career, I have been part of at least 70 different projects. It is extremely difficult for me to pick my favourite, the one that has had a bigger impact on society or the one that has affected my future the most. Although, I want to name some works and some of the people that were involved in them: Cartography of habitats in the Valencian Autonomous Community, with Carles Fabregat, Joan Casabó and Javier Fabado; Recovery of “Les Bassetes” public space (Benissa, Alacant); Research and collection of wild grown cereals and legumes for the Plant Genetic Resources Centre of the INIA, with Lucia de La Rosa and Alberto; Experimental winery “Les freses”, with Mara Bañó; Environmental restoration after the 2014 fire in the Montgó mountain, with Ignasi Astor; Study of the minority varieties of grape in Valencian territory, with Carmina Gisbert, Carles Giménez and Julio García.

Do you think these kinds of results have a notorious impact, even for the general public?

Many of the projects I have been involved in have had great impact. Actually, I have even received some awards and special mentions. I have done many things that have lasted over time: planting vineyards to make renowned wines, environmental restorations that are used nowadays, published works you can find on the internet and are sometimes consulted, books that have been sold, publications that are usually quoted… but I always feel that the things that have lived on until these days do not have the impact that they should. We live so fast, the only thing people want is to have short-term results, and that is impossible when it comes to plants. Great results are only possible after years of research. Plants need to grow and publications and research works must be revised and selected by science.

To sum up, the corporate world where I work values quick results: a finished plantation, a full finished garden, an environmental restoration completed on time, a book or a publication to achieve the project’s goals, and in the following years we will see if it was a work well done or not. I think this is not a good dynamic, especially when it comes to plants. Interventions and research are not only there to expand your CV, they must last through time.

How do you think your work has changed through the years?

For me, and I’m pretty sure for many “provincial botanists” as I call them, the change has been huge. I have around 4,000 books and documents about plants at home. “Why so many?” will younger people wonder. Well, in the past, in order to learn about plants you needed all kinds of books (determination keys, photo guides, flower guides, etc.) or just living next to the Library of the Botanical Garden of Madrid. Nowadays. You only need a computer or a cell phone and a good internet connection to find all the information you want. Furthermore, you can translate the texts and consult, even measure, herbarium material located miles away from you.

This was inconceivable to me. Just 20 years ago, I had to catch a train to Madrid or Barcelona, all excited and full of curiosity and expectations that I could never fully fulfill, because there was never enough time. I also have to say that, in the past five years, the improvement has been even better for botanists. I have witnessed all these changes and I feel lucky for it, I hope it can last through time.

What is the worst part about your job? And the best?

I have already mentioned some bad things about my job. Probably, one of the worst is the lack of judgement by the institutions and people who hire our services. Lately, there are fewer and fewer business owners, technicians and public managers with enough experience in the plant world. Consequently, they don’t really know what they want, and they don’t appreciate a job well done and with a future prospect.

Having good agricultural engineers, naturalists, natural science researchers and managers is becoming increasingly difficult. Nowadays, full dedication, permanent observation and acquiring the needed experience to become a professional in these fields have no recognition. It is very difficult in this urban and technological world. However, it’s very fulfilling to see your work can be more influential and reach more people thanks to the internet. So, we have to stay positive!

What is your relationship with the Botanical Garden of the University of València?

I consider the Botanical Garden to be my “scientific home”, I’ve been going there for a long time. A lot has happened in my life since the very beginning, when I used to talk to Jaume Güemes (the current director) in the old building about a Sub-Saharan plant I had found in Teulada, until the present, with all the new labs, new staff, the library or the herbarium. I collaborate with many people: Eva Pastor and Eli Caballer on botanical dissemination, visits and courses, among other things; with Xuso Riera and Javier Fabado, collecting Valencian flora material for the herbarium; and with the “alive” part of the garden, I help with the maintenance of the collection of minority vines from the Valencian Community.

What role does science dissemination play in society?

I think science dissemination is extremely important. We must pass to society all this knowledge we have acquired during our careers. It is simply fair because, in the end, all our neighbours have contributed financing infrastructures, universities, etc., so we could acquire this knowledge. Documenting my work, so it can be useful to future generations, is a must.

I spend most of my time taking pictures, writing, researching and checking my daily work, that is generally long term. So, I think it could only be assessed after some years. That is why, whenever I can and with the help of many friends like Lluís Serra, Antonio Hurtado, Carles Fabregat, Enric Martínez, Toni Santonja, Tonet Pérez, Carmina Gisbert and many more, I try to transfer all my knowledge through books, scientific dissemination articles published in all kinds of magazines, foundations, talks, guided tours…

In all these years as a botanist, have you been in any weird or funny situation?

I went to Madrid to get Félix Muñoz Garmendia’s personal books, probably one of the most important personal collections in the history of Spanish science and botany. It was 2015, I will never forget that day. I loaded the van with more than 1,000 books and boxes full of documents. After many hours selecting and loading documents into the van, I left the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid around eight at night. It was almost 1 AM when I was stopped by police, carrying machine guns, and asked what was in the van. I told them there was a library. They couldn’t believe it, so they searched the van. In the end, they thanked me for saving part of the botanical history of our country.

Do you consider yourself a pupil of any botanist in particular?

Professors Gonzalo Mateo and Isabel Mateu shaped my career as a botanist when I was still in uni. Later, Carlos Aedo, Ginés Lopez and Félix Muñoz Garmendia from the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid helped me at the beginning of my career, and we have been good friends since.

And, of course, I need to thank Pep Toni Roselló and Carles Benedi for helping me understand such important sciences as Biosystematics and Nomenclature.

In what era of Botany would you have loved to live?

During the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. It was the golden era of Botany, when studies about diversity were well recognized. Nonetheless, as I have previously said, the last few years have offered us the possibility of sharing and consulting information about flowers globally. Despite the lack of social repercussions of floral studies, I think this is a milestone for the world of Botany.

What botanist would you have loved to meet?

Pierre Edmon Boissier (1810-1875), a botanist, mathematician, and explorer from Geneva. I would have loved to travel with him around the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean Basin. Among the Spanish botanists, definitely Carlos Pau. Botanizing side by side with him would have been a dream.

In case of a fire, what would you save from your office?

As I have said before, I own tons of books, documents, slides and, above all, more than 15,000 herbarium sheets. I would be devastated if I were to lose the work of a lifetime. Fortunately, I can save it all in a small disk, so I would definitely save my hard drive.

n addition, I’m proud to say I have invested a lot of time in my herbarium and I have sent many sheets (more than 6,000) to the most important public herbariums: Madrid, Barcelona, València, and even Washington and Geneva.