Botanist of the month: Isabel Martínez-Nieto

She is a person with an insatiable curiosity and this is evident when she talks about all the facets she develops, both in the field of botany and in other areas. She says that the fact that she comes from a family dedicated to agriculture surely influenced her vocation. She likes the opportunity that science offers her to be constantly learning. She considers it necessary to disseminate and communicate with society on a permanent basis, and we at Espores can attest to this. Isabel Martínez-Nieto is our Botanist of the month.

What attracted you to Botany?

I suppose that I have been in contact with nature and, especially, with the world of plants since I was a child, as I come from a family involved in agriculture, and this may have influenced my interests. During my degree, although there were no specific pathways, I was always more interested in subjects that dealt with botany, vegetation and various aspects of plants in general. After all, they are the organisms that structure terrestrial ecosystems and define them, and they are at the base of food chains.

What has your professional career been like so far?

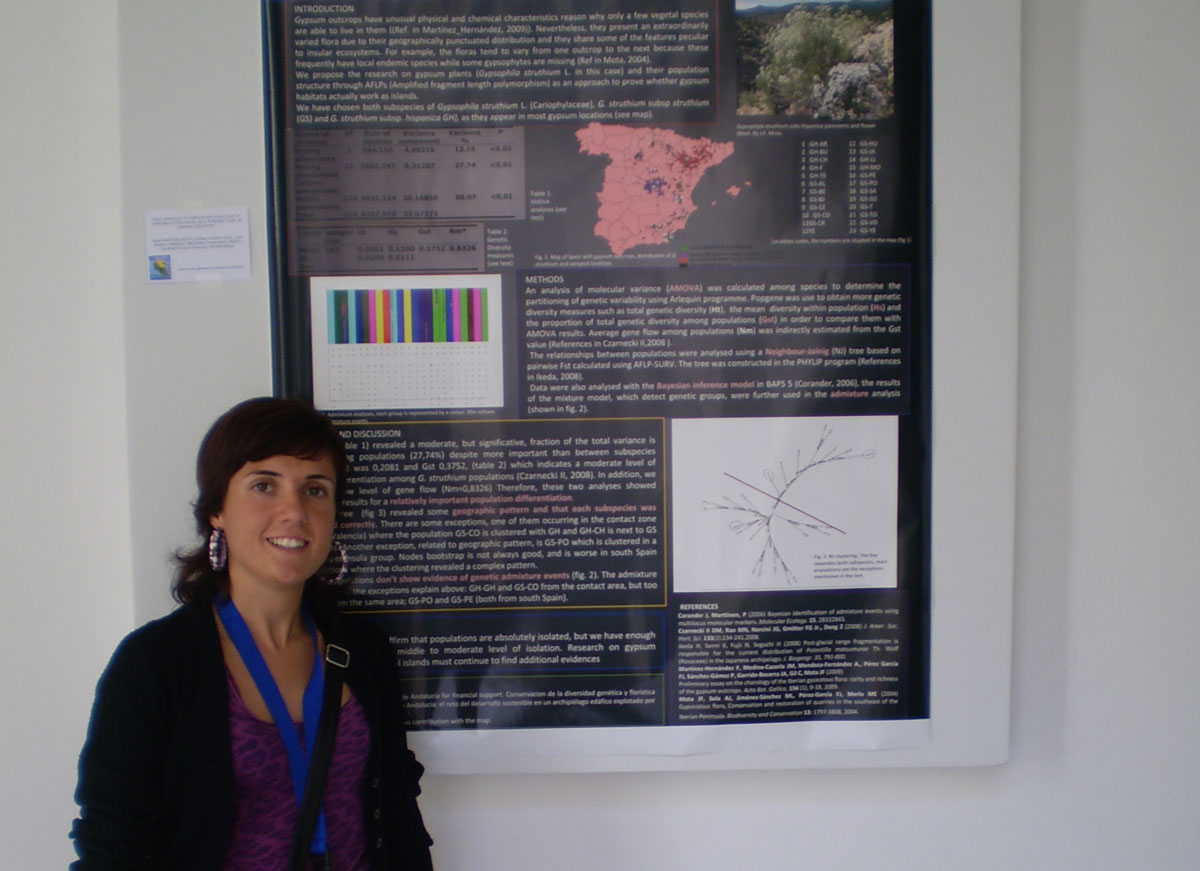

I started collaborating, on a semi-professional basis, in the laboratory of Isabel Mateu – who had been my professor at T.A.C.O. (Automated Classification and Organisation Techniques) and had just been awarded a project on phylogeography of Mediterranean plants -, and I found the field of research that I am most passionate about. Later I did my PhD at the University of Almeria with Juan Mota’s magnificent team, also in phylogeography and other topics related to plant conservation, but in this case those that grow in soils rich in gypsum. There I was able to continue working on these subjects for a while. Then I returned to the University of Valencia, again under the guidance of Isabel Mateu and together with the botanist and researcher Eva Barreno, on a project related to the strawberry tree in which I learned a lot about techniques that I had not mastered. In recent years I have continued in Eva Barreno’s group and I have started my career at the Jardí Botànic, initially in the Germplasm Bank, although now I do not only carry out tasks for this unit. I would love to be able to continue here for a long period. On the other hand, the precariousness that characterises a scientific career has led me to do all kinds of things between contracts, always in the field of education, and also to reinvent myself and become the versatile botanist that I believe I am today.

So what is your current job about?

As I mentioned, I currently collaborate with two research groups with which I carry out a wide range of activities, from purely microbiological work related to the symbionts of lichen systems, to updating plant biodiversity databases, to work related to phylogeography and other molecular techniques dedicated to the study of plants.

Your speciality is phylogeography, what interested you in this field of study?

I am involved in many branches of plant biology. However, it is phylogeography that is the field I know most deeply and, without doubt, the one that excites me the most. It is a relatively new field, emerging from the development of molecular techniques at the end of the 20th century. Phylogeographical studies try to unravel the historical processes that might be responsible for the current distribution of different organisms, based on different evidence, but mainly on the study of molecular marker genealogies. I find it a lot of fun, it could be compared to detective work in which we use the same molecular techniques as forensic scientists, but we also go out into the field to get first-hand knowledge of the distribution of the species and use other climatic or fossil-related data. Finally, we carry out exhaustive bionformatics work that makes it possible to solve the case. I love the fact that we break the trichotomy of belonging to the sector of “boot”, “lab coat” or “key” biologists… we do it all and this diversity makes it very entertaining.

Tell us what project you are working on at the moment.

I am currently involved in several projects. On the one hand, I have been working for a couple of years at the Jardí Botànic where I collaborate with different aspects of the maintenance of the Germplasm Bank and implement molecular analyses, phylogeographic or phylogenetic type, in some of the projects that are being developed. On the other hand, I also collaborate with the Symbioliquen research group, directed by Eva Barreno, in which I am currently involved in the isolation of microorganisms associated with lichen complexes…

Are you proud to have been involved in a particular project?

I am very excited to be part of a project related to the Cartagena Rockrose, which is considered the most endangered plant species in Spain, to the point that there is a national working group, as there is for the lynx or the bearded vulture.

I currently spend a large part of my professional career in the Jardí. However, it is a space that has always fascinated me and even more so since I started collaborating in the Botany Department of the University of Valencia, which is why I feel so proud to belong to the family of the Botànic.

Has your work changed over the years?

My career is not yet too long, but I have experienced first-hand the exponential development of molecular techniques. When I started, sequencing a fragment was relatively expensive and we were mostly working with other types of molecular markers. Today, with the implementation of massive sequencing techniques, whole organisms can be sequenced in just a few hours for a very competitive price.

How would you encourage current biology students to pursue the same career as you?

I am not so sure if I would encourage them to do what I do, it is a tough field that involves many periods of job insecurity. However, it is a fully vocational job, which is lived and enjoyed. So I would only encourage students to live it that way, to feel that biology is their great hobby, otherwise it is impossible to follow this career for long.

Have you met interesting people through your work?

Yes, a great many. Starting with a whole network of Spanish botanists with whom I have had the good fortune to collaborate on some occasion or coincide with them in some way. I was delighted to meet Jesús Izco, author of the main book in which we studied botany during my degree, at a congress we organised when I was at the University of Almería; or Gabriel Blanca, who was the president of my thesis tribunal. I think both meetings were very enriching, because they highlighted a couple of great figures in national botany.

Internationally, mostly thanks to scientific congresses, I have met scientists of the stature of the Grants -Rosemary and Peter grant, heirs to Darwin’s work- and extremely important biologists from my field such as Frederic Medail for phylogeography or Michael Moore, who studies gypsum plants at the Coahuila dessert in Mexico. It is truly fascinating, being able to have a conversation with people whose work guides your own research day by day.

Does your work allow you to learn about non-botanical subjects?

In my case, I learn about a wide range of scientific knowledge because of the diversity of work I do. But I think that being in science above all helps you to see life from an analytical and calm perspective.

How important do you think scientific outreach is?

There is no point in doing science in a cave, aimed only at experts. Our work depends on how useful we are to society, and we must convey this message to them. On the other hand, we live in the age of communications, surrounded by information of all kinds, by post-truths that are nothing but falsehoods. I believe that scientists have an important role to play here, at least with the information that concerns our fields of knowledge. We cannot all be experts in everything, but a little didactics on the part of the experts in each area can help us to gain judgement in the face of so much information interference.

You have talked about the difficulty of making a career in science. How do you assess the employment situation in the sector?

In general, a career in research has always been very complicated and, specifically in Spain, it involves many periods of job insecurity. However, I believe that at the moment, training in some branches of biology, such as biotechnology, molecular biology or bioinformatics, offers a promising career opportunity in private companies. A good example is the large number of personnel with biological training that is being needed to manage the pandemic we are experiencing due to SARS-COV-2: basic research on the virus, on its evolution, work applied to the development of treatments and vaccines, even for the implementation of the various techniques to detect those who are or have been infected.

Whose disciple do you consider yourself to be?

Perhaps not exactly a disciple, but there are some botanists to whom I have a lot to thank. I think the main one is Isabel Mateu, whom I consider my greatest mentor, as she opened the doors of the Botany department and introduced me to the field of phylogeography. She is a person who has always been there. But there is also Juan Mota, my thesis supervisor and one of the most integral people I know. I must also mention the multidisciplinary Eva Barreno, with whom I learn every day. And in recent years I could not be more grateful to the Botànic team with Elena Estrelles, Pilar Soriano, Jaime Güemes… a team in which I think I have integrated very well and with which I would like to continue working for a long time.

What era of Botany would you have liked to live in and why?

From a somewhat romantic point of view, I would have loved to have lived through the era of the great voyages with Humboldt, Darwin… surely there were many hardships, but before them a whole exciting world was opening up to be discovered.

Which botanist would you have liked to meet in person?

The scientist I would have most liked to meet is not a botanist, but rather an evolutionary biologist who revolutionised the theories of evolution in its most profound aspects in the last century, and whose work influenced, has influenced and continues to influence all branches of biology. This scientist is Lynn Margulis, whom I had the opportunity to listen to live at what was her last conference in Valencia. Without a doubt, I would have liked to talk to her and meet her personally, not only because of her findings but also because of her combative, rebellious and enthusiastic character.

In all these years as a botanist, what is the most curious situation you have come across?

It is especially on field trips that most anecdotes happen. I always remember that, after collecting samples for my thesis, one afternoon in July in the Monegros desert, when I returned to the car feeling dizzy and drinking water, I discovered how easy and dangerous it can be to become dehydrated. Another memorable moment was when, also with the group from Almería, we had to spend the whole day at the top of Gúdar, where there was no coverage, and a colleague’s wife was about to give birth. Sampling alone, I also met an unpresentable person who made me feel a bit uncomfortable. And collecting seeds for the bank, I remember a moment when there was a cloud of flies similar to fruit flies trying to get into my eyes, I don’t know if it was because it was the most humid area exposed, but it was really unpleasant.

Do you work alone or as part of a team?

I work in a team, which I find very enriching and I love it. I think that nowadays, in order to develop a competitive project, multidisciplinary teams are essential, as there are so many flanks to approach botany that it is impossible to be an expert in all of them.

What is the worst part of your job, and the most rewarding?

They say that patience is the mother of science, and so it is, you need a lot of perseverance to get results, and the precariousness that makes you jump from contract to contract often truncates a line that you had put a lot of hope into. However, when you are in a project, you start to get results and analysis after analysis the pieces start to fit together, it is a really gratifying feeling.