Botanist of the month: Belén Albertos

The plant world's great diversity awakened the vocation of our botanist of the month, Belén Albertos. Instability and perseverance define the career of this bryophytes specialist, who works for its conservation. A rather complex task, given that due to their small size and lack of funding, –although playing a crucial role in ecosystems– mosses are generally little known to the public and science. Travels, gardens, and art are other passions of this researcher and professor at the Universitat de València. She considers curiosity to be the teaching cornerstone.

What attracted you to botany?

I guess what fascinated me about plants was realizing how close they are. They are surprisingly so affordable when you give them a little attention. I did a field trip to Doñana during high school, under the impression that I had never learned so much in such a short time and with so much pleasure. Although we saw many animals, we saw many more plants, in such a diversity that seemed infinite. And plants were always there, without the need to be waited or wait for them. The first scientific names I discovered were plants’ names, a revealing experience. At the university (Autónoma de Madrid) I was lucky because –although I lost all of the second quarter of my second year due to several strikes– I did the first half of the course with Vicente Mazimpaka. It has been more than enough to decide my vocation. I started to collaborate with him and Paco Lara the following year, and I ended up doing my bryology doctoral thesis with them.

Could you summarize your career path?

My trajectory is a little heterodox, not because I have done very strange things, but because it has not followed a clearly ascending path. It rather seems to have been sinuous and full of setbacks. From my current perspective, I can say it has always been an advance. As it happens to the planets, it just may seem a strange and retrograde movement from a certain point of view.

I started with a very dense and complete doctoral thesis at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, through which I developed as a bryologist. I learned about bryophytes (especially epiphytic bryophytes), biogeography, and ecology. A phase carried out under not advantageous conditions because of grant lack. After about fifteen years devoted to science, with very dark perspectives, I came to a personal and emotional fatigue point that did not let me continue the path. I left botany for a while when arrived in Valencia and, when I got better, I hooked up with it again –but with a technical professional perspective. I needed to feel that all my formative baggage was useful to make a living. It seems obvious, but I can assure you that it is not. I’ve been working with contracts and commissions for many years, and I was turning my line of work towards general plant conservation –to the bryophytes conservation only when has been possible. Finally, against all odds (or at least against mine), I obtained a position as PhD assistant for two academic years at the Universidad de Valencia. It has brought me back into academic and scientific life.

I can say I ended up at the point I ran away from but with an enriched perspective –thanks to the contact I had with other worlds–, with a little more poise, and a lot of desire to do things. At the time, I experienced the changes I have gone through as failures. Now, I really start to appreciate what brought me to walk along secondary paths for much of the way.

What does your job consist of?

Well, that depends on which part of my trajectory you look at. My job routines have undergone dizzying changes over time. From intense identification work, with a magnifying glass and microscope, many field samples in different places and with different objectives, to computer work analyzing data or writing reports or articles. I have also had enough of organizing work teams and project management and brutally different things like organizing exhibitions, workshops, and outreach activities in the Jardí Botànic de la Universitat de València. I now add teaching in class, in the laboratory, and, on top, in both face-to-face and virtual format. I have to admit I enjoy changing routines a lot.

I’m sure that of all the projects you’ve worked on, there is a special one you are proud of, isn’t it?

Two projects left a big mark on me. ABrA (Atlas y Libro Rojo de los Briófitos Amenazados de España) was a very important leap for me. I entered the world of plant conservation with this project, which allowed me the professional development I needed and marked my current line of research. It is a field needing attention within botany and I am proud to contribute a little. Having been able to work in Antarctica is also a privilege I am very grateful for and I would like to repeat. There, my conservation interests –concerning human impacts on vegetation in this case – converge with a very special human and scientific experience.

Photoshoot in Antarctica. Photo: R. Jijón

What project are you developing at the moment?

I’m developing a conservation project, BRYOS, –supported by the Fundació Biodiversitat del Ministeri per a la Transició Ecològica i el Repte Demogràfico– which, I hope, will give a new impetus to the bryophytes protection in the country. It is being very interesting from the beginning. Spain has serious difficulties with bryophytes conservation commitments –protected by European conventions– due to the information gaps we want to cover. Furthermore, the project aims to increase the protected species list, which in the case of bryophytes is currently anecdotal. It is a vicious circle that prevents us from improving our knowledge. The funds are restricted to listed species and without funds, the necessary knowledge in order to properly evaluate them is not generated. It is a very varied project, as I like. There are many fronts needing to be covered. It is the most stimulating aspect of conservation and its major difficulty at the same time. It takes a lot of diverse knowledge to make the right decisions. Bryology is having a very remarkable development in Spain, but not in every area. We need to learn more.

El Atlas de los Briófitos Amenazados de España, coordinated by Ricardo Garilleti and I in 2012, and the BRYOS project are the conservation line’s past and present I develop.

I also participate in mosses family taxonomy projects (Orthotrichaceae) within the team I trained in, which is now larger and more powerful. It is mainly distributed between Madrid (UAM) and Valencia (UV). In the Ministeri de Ciència i Innovació project just awarded to us (OTHOCRYPT), we will explore the cryptic diversity of the family, which is proving to be extraordinary. Having the team’s support has been fundamental in order to be able to relaunch my scientific and professional activity. Collaborating with one of the most internationally recognized teams in bryophyte taxonomy is also a joy and privilege.

How are you related to the Jardí Botànic UV?

I worked there, in the Culture department, two times and it was a revealing experience. It gave me the opportunity to develop new skills, work in a completely different way, and collaborate with many valuable and charming people. I particularly value the opportunity to enter the scientific outreach world, to which I would like to devote more time.

Since botany suffers the easier perception of animals over plants by the public as a handicap, one could imagine that bryology –where we deal with very small plants– suffers this Plant Blindness to the full. It is urgent and necessary to vindicate these organisms’ importance, both former and current, which play a crucial role in the ecosystems as much as in the planet’s biogeochemical cycles.

Have you met interesting people thanks to your job?

Many, yes. Aside from my colleagues, and companions of more or less long adventures, much of my social circle is directly or indirectly related to my job. Sometimes, I have met people in scientific contexts and then consolidated our friendship around other kinds of things having nothing to do with it –but that unite us even more. I have a group of friends, for example, formed around science joined by other friends dispersed in four provinces. We get together to catch up as much as possible. We are a somewhat peculiar group, a wonderful support network that would be good for a film script, really.

And there is, of course, my husband Ricardo Gariletti. We met in the UAM bryology laboratory and we have shared life more intensely than most couples since then. If I had been told all of this when I was 20, I would have run away. But I have never really felt the burden of the hours we spent together (almost all day every day). He’s the best partner in my life, in all facets.

And as a botanist, what is the most curious or amusing situation you can tell you have found yourself in over the years?

Among the funniest anecdotes, there are several from Japan. There, we spent almost a month in rural areas, where English is not widespread at all. Every communication attempt, through automatic translators and my rudiments of Japanese, was quite an adventure. We went to a post office to send some samples on one occasion, and the official asked us about the package contents. There were mosses, I explained, and even if he was surprised seemed to understand (koke, koke!). He checked his checklist and asked undeterred, “bateries?” I kept my composure and replied very seriously that they did not have batteries. We still argue about what that man could think we were sending.

Also Galicia, the territory I studied for my doctoral thesis, has given birth to a lot of stories. It was normal to get lost every two days in that world of scattered villages, councils, hamlets, and repeated place names, without any GPS. When that happened, there was always a villager leaning on his crock, watching us come and go, without saying a word. When we finally decided to ask (something we avoided because we knew how it would end) there were two possible answers: “why do you want to go there?” or “there is nothing there!”. But the Oscar to the best answer goes to the man who, without separating his chin from the stick, simply told us “you are going wrong”.

During all these trips, there has also been some unpleasant encounter, fortunately never so dramatic as not to end up in the anecdotes’ sack and laugh about it. In Morocco, we suffered the police arrogance and desire to exercise authority, which caused us the loss of very valuable time –it has also been quite vexatious for the women of the team. Fortunately, it was nothing serious and these kinds of experiences usually end up strengthening ties in the team.

Do you think your job allows you to learn about not related to botany topics?

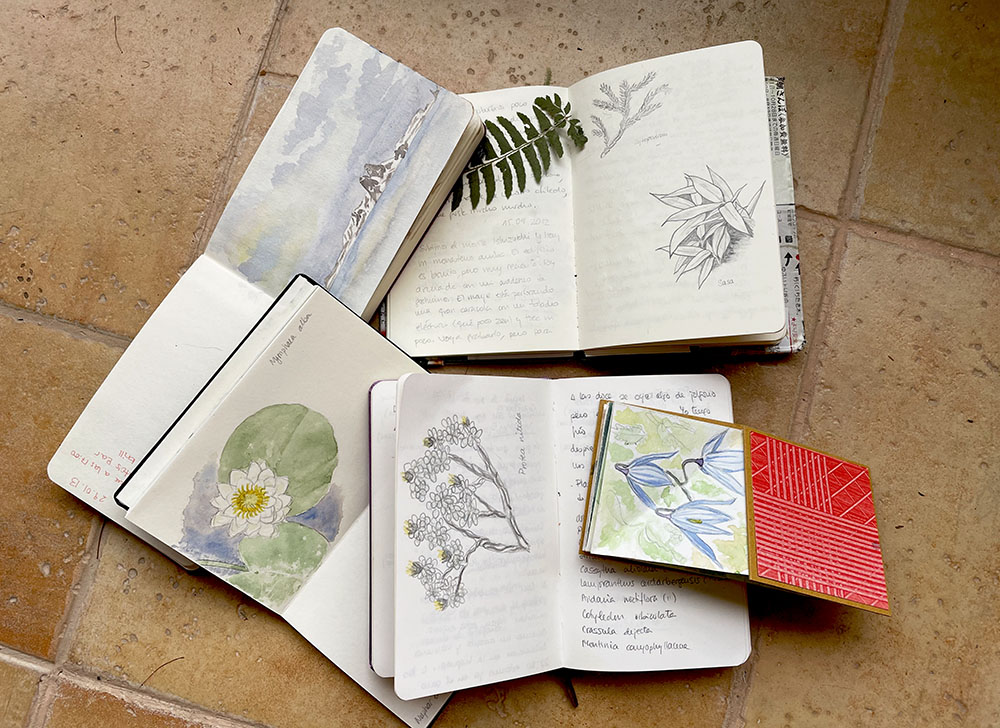

Traveling has given me a lot of perspectives. Not just about how life in other places is, how other biomes are, or how things are done in other countries. The view of your everyday things environment changes a lot once you come back home. My art appreciation, especially, has a lot to do with what my eyes have seen around the world. But I guess my passion for gardens is the most obvious one, nature knowledge really conditions my vision.

The first time I visited Japan, for example, was on a sightseeing trip and I visited many gardens. I was fascinated, like everyone else. I thought they were very beautiful and full of symbolism, but I also saw them as very formal, somewhat unreal. They have a different concept from the British ones, for example, which are more scenic, an English countryside mimicry.

On another visit to Japan, that of the mosses with batteries, we hardly set foot in the cities, focusing on the country’s natural landscapes. Experience that completely changed my view of the gardens. It is true that some of them are very formal, especially the dry zen gardens. But I found out many of the things I considered symbolic in the Kyoto gardens –like that perfect Ginkakuji sand flan– to be a reproduction of what you can find in the field. These things really exist! Japanese too imitate the landscape in their gardens, I just didn’t know about these landscapes.

What do you consider important in today’s teaching?

I started teaching very soon, right after graduation, in a garden design school. Many of my students were gardening professionals or architects. I also taught at the university after my thesis. But it’s been a long time ago, and now that I’m back to this activity my perspective has changed a lot. I’m still convinced that stimulating the natural students’ enthusiasm is the most necessary thing to do. Fortunately, in the degrees where I teach, there is a significant proportion of vocational people, which is a blessing for a teacher. The teaching’s cornerstone is curiosity today and always.

What has really changed is the fact that today teachers are no longer needed to transmit knowledge –since information is reachable within one click. Our function should be that one of a compass in the middle of an over-information sea. I would like to focus on stimulating students’ curiosity and judgment, rather than funneling information as if they were geese –which is the usual practice. We usually saturated them from high school on, doing nothing but seeing that something fails, since the next year they remember almost nothing. But getting what I’m looking for is not as easy as saying it. I think I’m just getting started and I hope to get closer to my goal every year a little more.

What future awaits botany, in your opinion?

The entry of molecular studies into botany has been a mind-boggling change. We are living a revolution that makes us consider many fundamental things, from the concept of species to the botanists’ formation, and work. We will probably be caught in the fog for a while (more than desirable), but I trust we will end up recovering some old botany things. Without them, the methodological advances will not take us as far as we would like to. The biggest problem is that old botany needs long training and we live in a world where there is a general hurry.

In the species conservation field, what concerns me the most is the bureaucratization of the efforts. Resources are scarce and only invested where there is a legal obligation. It is limiting, especially when talking about insufficient and inadequate protected species lists. On the other hand, we have more and more scientific and technical potential, which is obviously positive, but we don’t know many things yet –we know almost nothing about most of the species. Our point of view is partial and is dangerous to believe that we will be able to repair the damage we caused. We probably don’t –and won’t– even see that damage.

Do you work by yourself or as a team? Do you like working like this?

There is much talk about scientific collaboration and it is true that it is very important. But it is also essential to have a good capacity for self-employment in this world. Nobody would get a thesis without it. There is more and more collaboration because there are bigger and more specialties segmented teams. Furthermore, the fieldwork is usually done as a team since the more eyes and legs the better. But there is also a lot of lonely work in science, which I recognize is not what I enjoy the most. I feel more comfortable working with other people, in order to discuss details and possibilities. But in order to make run the team, every component has to be able to work on its own. I have had to coordinate groups of people and, getting consensus or making it properly run, is not that easy. But when it does work, it is one of the most satisfactory things.