Botanist of the month: Anna Nebot

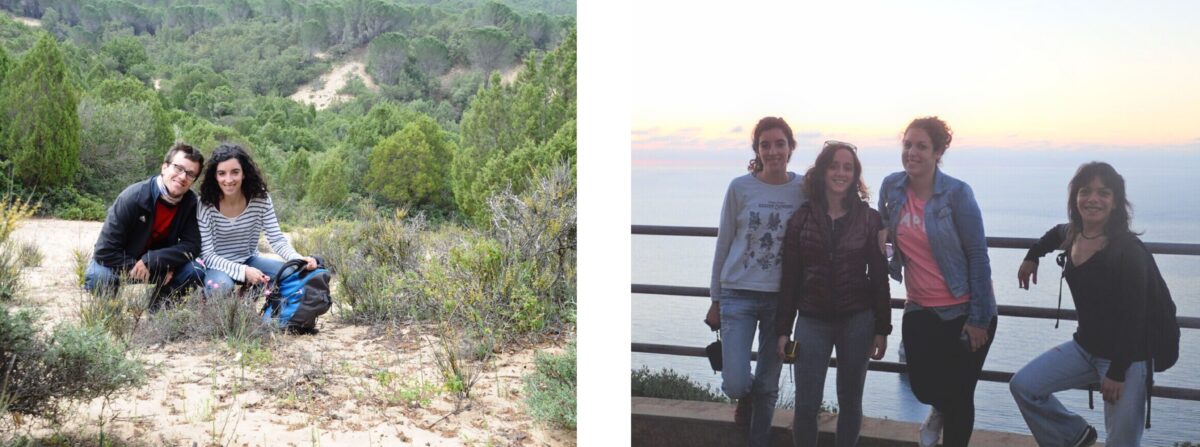

This July we are going with a young botanist full of enthusiasm to continue learning and making her way among plants. Anna is a good example of how a positive contact with botany during her studies and subsequent enriching experiences in different centres can turn curiosity and interest into dedication and a professional path. She focuses her work on the satisfaction of collaborating in the conservation of species, but also on the good fortune of being able to be in the midst of nature while working. We went out into the field with her and talked a bit about challenges, illusions and a lot of patience.

What attracted you to Botany?

Since I was very young I have had a link with the mountains thanks to my family, and perhaps this was the trigger that made me decide to study biology. For the first few years I didn’t know where I wanted to go with my studies, but while I was taking the botany course and going on the field trips to do the herbarium, it changed the way I observed the environment. Every week I repeated the same itinerary, but every week I observed new species at different phenological stages.

During the last years of my degree, I chose subjects that focused on botany, but the definitive moment came during the last year of my degree, when I did my external internship at the CIEF (Centre for Forestry Research and Experimentation) and my Final Degree Project (TFG) at the JardÍ Botànicof the University of Valencia. These two experiences and the people who trained me were the turning point for me to want to continue training in botany and especially in the field of plant conservation.

Could you summarise your professional career?

The first research work was carried out during the last year of my degree for the TFG. I studied the reproductive biology of Silene hifacensis, a species endemic to Alicante and Ibiza. When I finished my degree at the UV I got a Leonardo da Vinci grant that allowed me to spend 6 months at the CCB (Centro Conservazione della Biodiversità), located in the Orto Botanico of the University of Cagliari (Sardinia, Italy), where I was able to continue studying reproductive biology with endemic species of the island. After this stay, I started a PhD in applied botany at the same university and in 2017 I obtained my PhD.

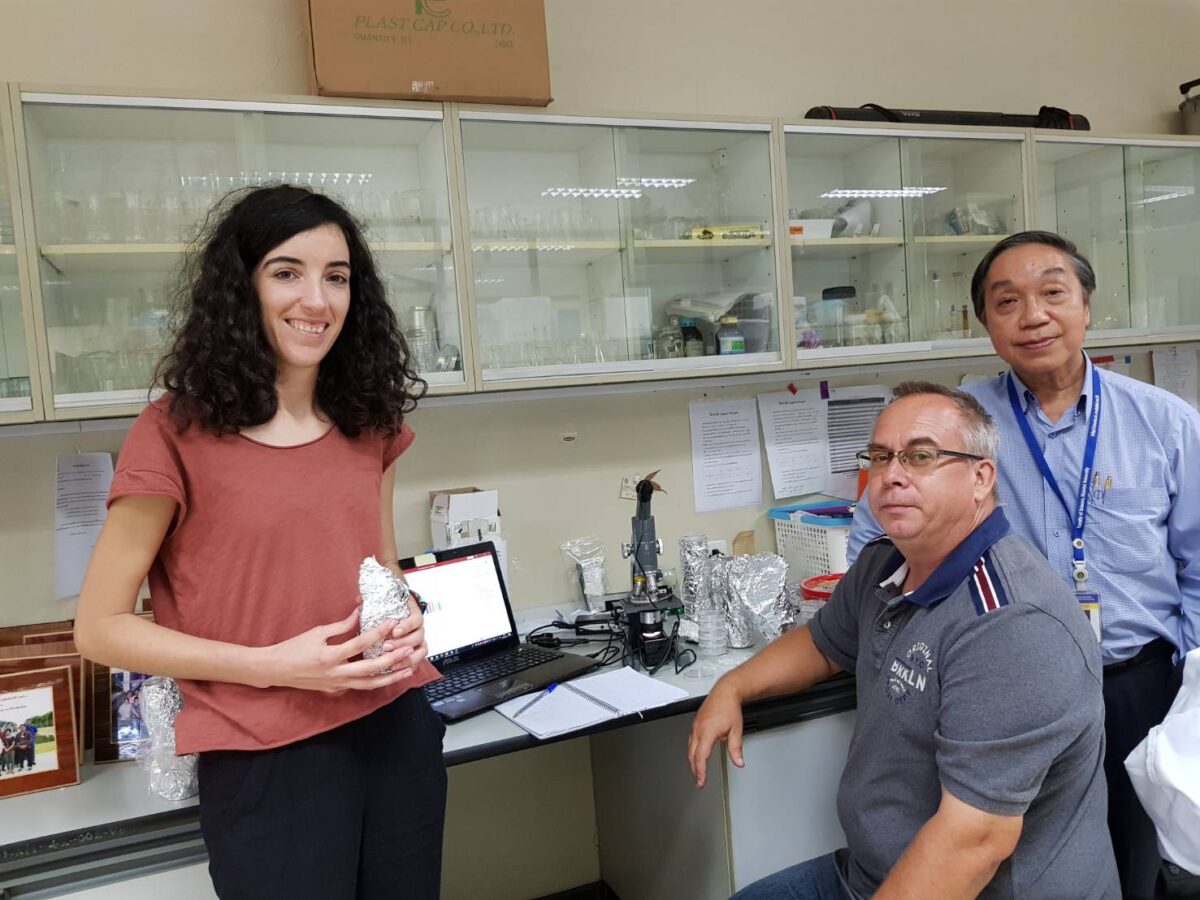

A few months after returning home, I had the opportunity to spend 6 months at the Department of Comparative Plant and Fungal Biology at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (UK) where I was able to acquire new skills in pollen conservation, developing short and long-term protocols. This knowledge led me to participate in a project to study the cycad pollen collection at the Nong Nooch Tropical Botanical Garden (Thailand), one of the most complete in the world.

As for the present, since 2020 I have been working at the JardÍ Botànicof the University of Valencia and I am in charge of carrying out studies to improve the conservation of endemic and endangered species of the Iberian Peninsula.

What does your work consist of?

I am currently in charge of studying the reproductive biology of two of the most endangered endemic flora species of the Iberian Peninsula, the Cartagena Rockrose (Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis) and Conejito in the mountain range of Gador(Gadoria falukei). In addition, I am also in charge of the rest of the field work related to these species, such as population censuses, research on new populations… Knowing how plants reproduce, their pollinators, the germination capacity of seeds and the habitat where they live can help us to understand the causes of their threat, and is very useful to be able to develop appropriate conservation measures.

Your speciality is the reproductive biology of endemic and endangered plants. What interested you in this field of study?

There are currently many threatened or endangered plants around the world. In order to conserve them, we need to know the species, so that we can develop effective conservation mechanisms both in situ (in their natural environment) and ex situ. Sometimes we find species that year after year are losing individuals due to biological or anthropological factors, and others, as is the case of one of the species I am currently working with, have only recently been discovered and there is still a lot of unknown information about them. These are unique species with very few representatives in the world and being able to contribute my studies and knowledge to improve their conservation is very satisfying. In addition, most of these experiments are carried out in the field, surrounded by nature and tranquillity, and I like that even more.

Are you proud to have been involved in any project in particular?

All the projects I have been involved in have been linked to highly endangered species, so I was very happy to have been able to contribute to improving their conservation. Of all the projects I would highlight two: the project carried out between England and Thailand, where I was able to develop protocols for the conservation of the pollen of numerous species, especially cycads (the most endangered group of plants in the world) and which can be applied by the numerous groups working with these plants all over the world.

The other project I am very proud of is about Gadoria falukei, a species that was described in 2017 in the mountain range of Gádor (Almería) and of which only 79 individuals are currently known in a single population. We already have seeds conserved in different germplasm banks and we are cultivating it in the JardÍ Botànic, where we are focusing on molecular and field studies, to locate new populations and be able to make introductions in the natural environment and thus increase the number of plants in the field.

What project are you working on at the moment?

I am currently participating in two projects and each of the species requires different approaches to the studies. The first project deals with the conservation of the Cartagena Rockrose (Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis) in Valencia, where only one individual was known in the natural population and currently numerous individuals have been introduced throughout numerous populations. Most of the researchers of the JardÍ Botànicof the University of Valencia are involved and I am in charge of monitoring the reintroductions and testing the reproductive capacity of the plants once they are established in the field.

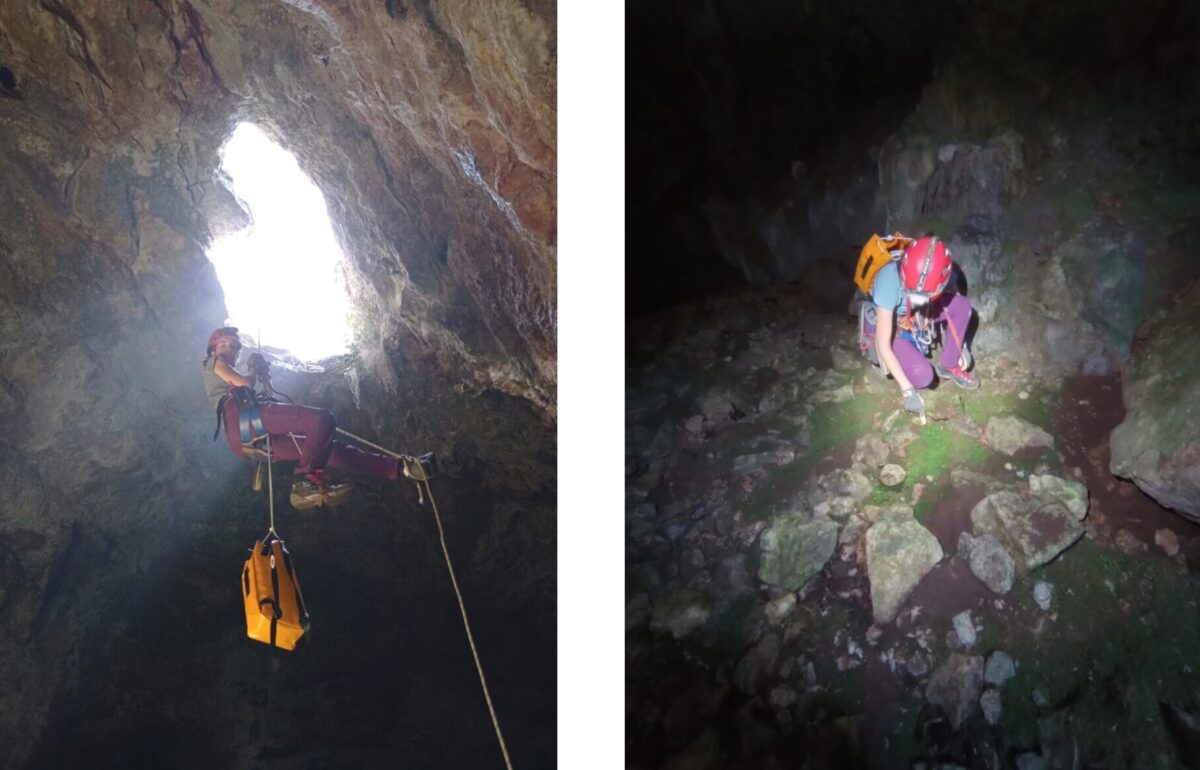

The second one is devoted to the studies of Gadoria falukei, with more field work, since it has only recently been discovered. This plant grows in a rock face and the vertical walls where it grows with high overhanging rocks do not facilitate the surveys. For each census, we photograph the different areas of the rock face to be able to determine more precisely the presence of new individuals, to see the evolution of known plants and to identify plants that have died. With the field data we are obtaining we will be able to estimate the evolution of the population. In addition, we continue to search for individuals in areas with the same climatic conditions.

What is your relationship with the JardÍ Botànicof the University of Valencia?

I did my first research work at the JardÍ Botànicunder the direction of Jaime Güemes. These experiments opened up a new field of study for me and were the start of my research career. And in 2020, after training in different laboratories, I returned to the JardÍ Botànic, where I am currently working as a research doctor.

How do you assess the employment situation in the sector?

Research in general in Spain does not receive as much funding as it should, and if we focus on botany even less. From the first moment I was warned that “biology had no opportunities”, that I should choose another career, but for me it is more important to study what I like regardless of the job opportunities, and there is always time to work in something else. Nowadays, it is very difficult to get a stable job as a botanist because contracts are usually temporary and there is a lot of competition for projects. What is clear is that it is a very vocational job and that is what makes us keep trying to work in the world of botany.

Does your work allow you to learn about non-botanical subjects?

Of course, in nature there are many factors that influence the plants we study. In my case, for example, it is important to know which pollinators are involved in the reproduction of the species I study, or what environmental conditions we have to recreate to be able to grow the plants we study outside their habitat. The sciences are interrelated and this means that we often contact specialists from other fields in order to be able to continue our studies, so that in each project we learn new skills in other fields.

Have you met interesting people through your work?

Throughout these years as a researcher I have worked in different international laboratories, some of them of recognised prestige, which has allowed me to work and meet many people from all over the world. I have met students and research staff who were just starting their research career like me, but also very important people in the world of plant conservation. National and international congresses, workshops and project meetings have also allowed me to meet people I had only known before as authors of research related to my field of study. On some occasions I have even been invited as a speaker at the conferences they organised. Of all these people, some have been so interesting that they have marked the path of my research career.

What is important to you in teaching?

This year I have had the opportunity to teach both in secondary school with secondary school students and at university with first-year students. I have realised that many of them are far from nature and therefore the first thing we have to do is to bring them closer to it, captivate them, awaken their curiosity for nature in general and for botany in particular, in order to reach them and provide them with the necessary knowledge. They have to understand the applicability of what we teach them in the classroom, so I think that if we could have more field trips it would be easier to attract students to our fields of study. Over the last few years I have had internship students, and for me the most important thing is to teach them different fields and types of studies, and to let them experiment to discover new skills and start defining where they want to go.

What is the role of outreach for you?

Today, a large part of society is more isolated from nature than in previous decades. I think it is very important to bring research and knowledge closer to society, so that they understand the importance of these studies, since the effort of all of us is needed to conserve nature. There is a lack of awareness about biodiversity and to reverse this we must first bring the studies that are being done about it closer to society. We all do not have the capacity to spread the word to the masses, but we can contribute to each of the visits that students make to us, to the visits to the JardÍ Botànicor in the day-to-day life of the people around us.

How would you encourage people who are currently studying biology to go into the same field as you? What do they need?

This job is very vocational and requires a lot of effort. It is not an easy career path, but if you really like it, it is very worthwhile. What attracted me to botany was the field work, observing, photographing, touching and enjoying plants and nature in general. It is clear that I have always been linked to nature, which is why once I was in my degree I knew I was a “bootstrap” biologist and little by little I discovered my affinity for plants. So I recommend that you go out into the field and try to apply your classroom knowledge to explore your environment and continue learning. Over the last few decades, field trips have become less and less common, which makes learning more difficult, but I am sure that once you return to the field on your own after having taken the different subjects in your degree, your perception of the environment will change.

In all these years as a botanist, what is the most curious or amusing situation you have come across?

Thinking about it now years later, I see it differently, but in the first year of my doctorate, when I had already done all the treatments on the plants and only had to wait for the fruits to ripen before harvesting them and analysing the results, one day I arrived and found a large part of the plants eaten, although the goats had been kind enough to leave me the nibbled sachets next to the plants. Field work is linked to inclement weather, plant phenology and the presence of animals in the study habitat, so when this happens there is no choice but to try to repeat the experiments before the end of the period or, if it is too late, wait until the following year and think of something to avoid losing the results of the experiments again.

What is the essential skill for your job?

I guess, as with many others, patience. Our experiments are linked to the phenology of the plants and therefore we work at their pace. Normally reproductive biology work is concentrated in 1-2 months of the year and you have to do it before the end of the flowering period, as you can’t do it again until the next flowering period. In addition, the weather also affects some of the experiments, so we cannot always carry them out on the right day. It is also very important to know how to move around the field. Each species grows in a different environment and to get to them we sometimes have to climb, abseil, climb cross-country, walk for a while, or all together as in the case of Gadoria falukei.

Do you work alone or as part of a team? What is it like to work like this?

The studies are always carried out as a team, as each person is in charge of his or her own specialisation and contributes his or her knowledge to achieve more complete results. Some of the laboratory experiments are carried out individually. As far as field work is concerned, nowadays I always go with someone else, as it is much easier to carry out pollinator censuses, population censuses and research into new populations in a group. During my PhD, many days I went alone to carry out the studies, so whenever possible I left the field trips that required little time for the weekend, so that I could be accompanied by colleagues or friends.