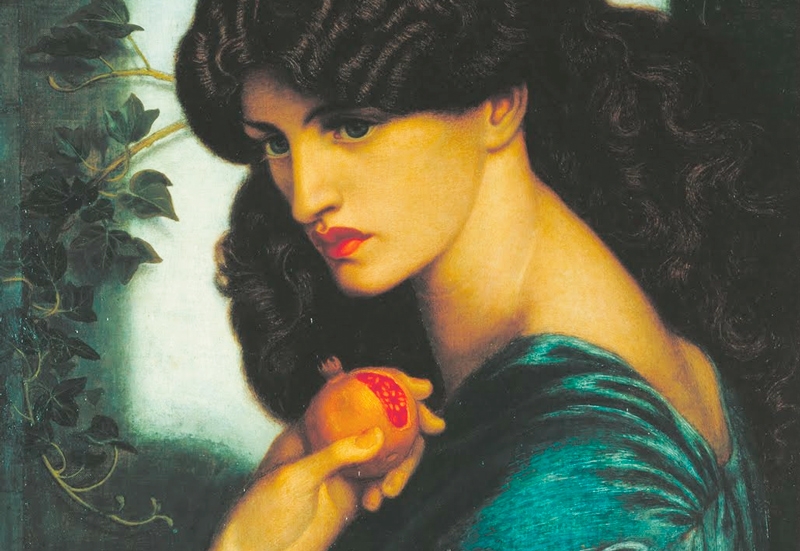

Proserpina or the botanical symbology of Dante Rossetti’s work

In order to understand the Pre-Raphaelite’s works, Dante Rossetti, it is necessary to know the meaning of the plants appearing or being mentioned in them. This is what happens with the sonnets and paintings dedicated to Proserpina, the Greek Persephone, the classical goddess of the dead's world. A works’ set in which the artist recorded the details of his complex relationships with Jane Morris in a plant key.

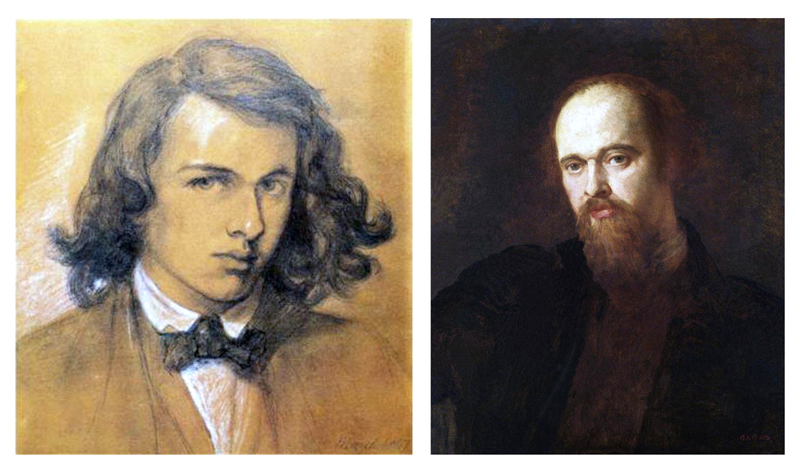

A British of Italian origin, the poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) was the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s leader. An artistic movement that was characterized, among other things, by using botanical elements to intuitively represent concepts.

On the left, Rossetti’s self-portrait dated 1847. / WikiArt. On the right, Rossetti according to a portrait painted by George Frederick Watts (c. 1871). / WikiArt

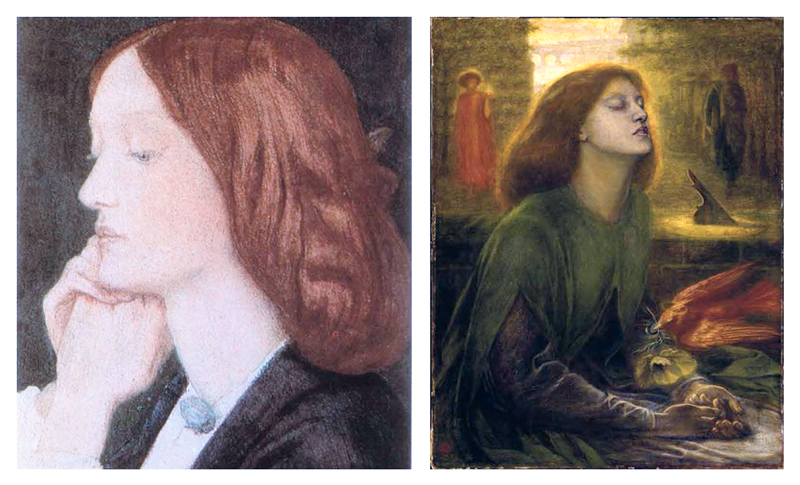

Famous for his youth appeal, Rossetti was a passionate man who seduced many of his models. Starting with the unfortunate Elizabeth Siddal, delicate beauty of reddish hair which he would end up marrying, and ending with Jane Burden, his colleague William Morris’s wife.

On the left, Elizabeth Siddal («Lizzie» for friends) portrayed in 1854 by her husband. / WikiArt. In poor health and with depressive tendencies, Elizabeth died of a laudanum overdose in 1862 (apparently intentional). Feeling guilty about his wife’s death, and shortly after losing her, Rossetti began painting his masterpiece, the haunting Beata Beatrix (1880), (above, on the right). A painting where he depicted a poppy white flower in order to immortalize Lizzie (Papaver somniferum L., Papaveraceae), symbolizing the preparation she used to commit suicide. / WikiArt

In the picture, Papaver somniferum (var. blanca). / Philmarin – Wikimedia

In the picture, Papaver somniferum (var. blanca). / Philmarin – Wikimedia

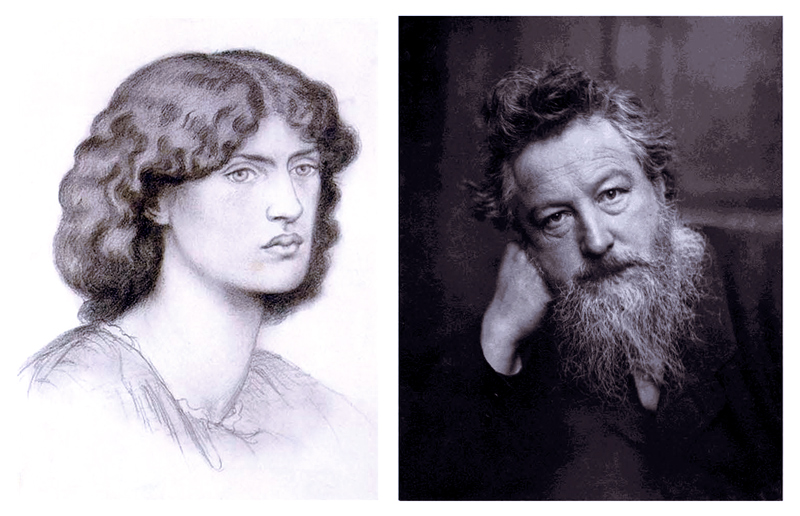

Apparently, Jane became Rossetti’s lover due to her marital unhappiness. Whit him, she would maintain a relationship that began in 1869 and lasted for several decades. During this time, Mrs. Morris would not only help the artist cope with the severe depression that tortured him from his wife’s death to the end of his days, but she also became his favorite muse and model, posing for many of his paintings. Among them, Proserpina.

In the photo on the left, Jane Morris (Rossetti, 1869-1870). / WikiArt. On the right, a portrait of the architect, designer, and writer William Morris (Frederick Hollyer, c. 1887). / Wikimedia Commons

In the photo on the left, Jane Morris (Rossetti, 1869-1870). / WikiArt. On the right, a portrait of the architect, designer, and writer William Morris (Frederick Hollyer, c. 1887). / Wikimedia Commons

The Proserpina myth and the seasons’ birth

Named Persephone by the Greeks, Proserpina is the protagonist of the classic myth explaining the seasons’ birth. According to it, while collecting flowers in Enna’s meadows, in Sicily, the goddess was kidnapped by Pluto, the underworld and dead’s god, who took her to his kingdom in order to marry her. Captive and longing for her life on earth, Proserpina ate a few grains of a pomegranate while in Hades, unaware that tasting the underworld food meant getting chained there forever. However, thanks to Jupiter’s intervention, Pluto allowed his recent wife to spend part of the year in the living world along with Ceres, her mother and cereal and agriculture goddess, who, happy to see her daughter, makes the plants bloom and bear the fruits.

Belonging to the litráceae family, the pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) is a shrub or tree, with numerous and normally thorny branches and deciduous leaves, shiny by the bundle and somewhat hard. Its striking flowers are red. Cultivated since ancient times for ornamental, food, and medicinal purposes, pomegranate is native to western Asia, extending from Turkey to Afghanistan; and was introduced into the Mediterranean account by the Carthaginians. / PDO Granada Mollar de Elcha – Wikimedia

Belonging to the litráceae family, the pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) is a shrub or tree, with numerous and normally thorny branches and deciduous leaves, shiny by the bundle and somewhat hard. Its striking flowers are red. Cultivated since ancient times for ornamental, food, and medicinal purposes, pomegranate is native to western Asia, extending from Turkey to Afghanistan; and was introduced into the Mediterranean account by the Carthaginians. / PDO Granada Mollar de Elcha – Wikimedia

The scientific name of this plant, deriving from the Latin words punicus, -a, -um = cartaginés, púnic and granatus, -a, -um = magraner, abundant in grains or seeds, is in allusion to the grains that form its fruit. / Adrian Cerón – Wikimedia  Besides being Proserpina’s mother, Ceres (Demeter for the Greeks) was the Roman goddess of crops and cereals. The Poaceae family plants are sown because of their fruit (grain), whose name derives from that of this divinity. In the image, Ceres (Osmar Schindler, 1900-1903). / Wikimedia Commons

Besides being Proserpina’s mother, Ceres (Demeter for the Greeks) was the Roman goddess of crops and cereals. The Poaceae family plants are sown because of their fruit (grain), whose name derives from that of this divinity. In the image, Ceres (Osmar Schindler, 1900-1903). / Wikimedia Commons

Rossetti’s Proserpinas

Rossetti, a great connoisseur of Greco-Latin mythology, took the Proserpina story as the basis for his homonymous painting. A work described by Rossetti himself in the 1878 text, collected by Sharp in his 1882 study, that we translate below:

“The figure represents Proserpina as Empress of Hades. . . The goddess stands in a shady corridor of her palace, with the fatal fruit in her hand. On the wall behind it is reflected the light coming from an entrance that, suddenly open, communicates for a moment the underworld with the higher world. Immersed in his thoughts, Proserpina takes a sneaky look at it. The incense burner that appears [in the lower-left corner of the picture] is a divine attribute. The ivy branch of the background [a decorative addition to the sonnet written on the bracket] can be taken as a symbol of lasting memory”.

Above, on the left, pomegranate and fruits illustration in the Gottorfer Codex (Hans-Simon Holtzbecker, 1649-1659). / Wikimedia. On the right, ivy illustration in Flora Londinensis (William Curtis, 1777). / BHL

Ivy (Hedera spp., from the classical Latin edera, -ae = ivy, a word that comes from the Indo-Germanic ghed- = to catch, to grasp), typical of shady and often cultivated places, are climbing plants of aralyaceae family and can be found in Europe, Asia, and North Africa. They have perennial, bright, and rather hard leaves. Those leaves that sprout from the branches with flowers (green color) can be oval or round; the others have a palmate shape. The ivy fruit has the approximate size of a pea, is fleshy, black once ripe, and toxic as the rest of the plant. / Alexphoto – Freepik

Ivy (Hedera spp., from the classical Latin edera, -ae = ivy, a word that comes from the Indo-Germanic ghed- = to catch, to grasp), typical of shady and often cultivated places, are climbing plants of aralyaceae family and can be found in Europe, Asia, and North Africa. They have perennial, bright, and rather hard leaves. Those leaves that sprout from the branches with flowers (green color) can be oval or round; the others have a palmate shape. The ivy fruit has the approximate size of a pea, is fleshy, black once ripe, and toxic as the rest of the plant. / Alexphoto – Freepik  Jane Morris is also the model of La Pia de’ Tolomei painted by Rossetti between 1868 and 1880. / Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas – Wikimedia

Jane Morris is also the model of La Pia de’ Tolomei painted by Rossetti between 1868 and 1880. / Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas – Wikimedia

The sonnet to which Rossetti refers, composed in Italian and of which he is also the author, is entitled Proserpina. The first version, 1872 dated, is as follows:

Lungi la luce che in su questo muro

Mi giunge appena, un breve istante scorta

Del mio palazzo alla lontana porta.

Lungi quei fiori d’Enna, o lido oscuro,

Dal frutto tuo fatal per cui snaturo.

Lungi quel cielo dal tartareo manto

Che qui mi cuopre: e lungi ahi lungi ahi quanto

Le notti che saran dai dì che furo!.

Lungi da me mi sento; e ognor sognando

Cerco e ricerco, e resto ascoltatrice;

E qualche cuore a qualche anima dice,

(Di cui mi giunge il suon di quando in quando,

Continuamente insieme sospirando)—

“Oime per te, Proserpina infelice!”.

Rossetti (1970)

Some time after writing the quoted poem, Rossetti would compose another mourning sonnet with the same title and theme, but in English:

Afar away the light that brings cold cheer

Unto this wall, – one instant and no more

Admitted at my distant palacedoor.

Afar the flowers of Enna from this drear

Dire fruit, which, tasted once, must thrall me here.

Afar those skies from this Tartarean grey

That chills me: and afar, how far away,

The nights that shall be from the days that were.

Afar from mine own self I seem, and wing

Strange ways in thought, and listen for a sign:

And still some heart unto some soul doth pine,

(Whose sounds mine inner sense in fain to bring,

Continually together murmuring,) –

“Woe’s me for thee, unhappy Proserpine!”.

Marillier (1899)

Up to eight Proserpina versions

There are at least eight oil versions of Proserpina, although just a few of them are complete. It’s something that allows us to get an idea of Rossetti’s interest in this pictorial composition, which had great emotional importance for him. In it, the painter codified the details of the complicated triangular relationship he was involved in. In fact, he used Jane as a model because identified her with the underworld goddess. Like Proserpina, she was an unhappy wife condemned to a dark existence with a husband she did not love. Hence, the divinity’s sad expression and the open grenade, which is a botanical symbol referring, in this context, to the captivity she was condemned to by an unhappy marriage forcing her to remain in a dark world. From where she could escape only during the short periods of freedom lived with her lover.

Bibliografia

Curtis, W. (1777). Flora Londinensis. Vol. 1. Printed for and sold by the autor. London.

García, C. (2008). De Circe a Psyque: mujer y mitología en los pintores prerrafaelitas. Materiales de Apoyo a la Acción Educativa. Centro del Profesorado y de Recursos de Gijón, Consejería de Educación y Ciencia. Gobierno del Principado de Asturias.

Marillier, H.C. (1899). Dante Gabriel Rossetti: an illustrated memorial of his art and life. George Bell & Sons. London.

Rossetti, W.M. (1970). Dante Gabriel Rossetti: his family-letters with a memoir. Vol. II. AMS Press. New York.

Sharp, W. (1882). Dante Gabriel Rossetti: a record and study. MacMillan & Co. London.

Altra bibliografia consultada

Álvarez, B.T. (2013). “Beata Beatrix”: un fascinante ejemplo de simbolismo floral en el arte. UAM Gazette.

Doughty, O. (1949). A victorian romantic: Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Frederick Muller Ltd. London.

López, G. (2002) Guía de los árboles y arbustos de la Península Ibérica y Baleares: especies silvestres y las cultivadas más comunes. Mundi-Prensa. Madrid.

Marecki, M. (2004). Proserpine and Jane Morris: women trapped in unhappy relationships. The Victorian Web.

Nahum, P. & S. Burgess (2006). Proserpine. The Victorian Web.

Ringel, M. (2004). Longing and connection in D.G. Rossetti’s “Proserpine”. The Victorian Web.

Zurriaga, F. (2008). El granado: la tradición perdida. Mètode, 59.

Articles d'Espores

Climent, D. (2012). Perséfone, del narciso a la granada. Revista Espores, la veu del Botànic.

Redacción de Espores (2013). Los dioses de la agricultura: mitos y leyendas. Revista Espores, la veu del Botànic.