The urban orchards expansion in València

In today’s society, there is a need of looking for new ways to inhabit cities, reinventing time, and modifying spaces that bring us closer to nature. Urban horticulture adds the pleasure of seeing the development and plants’ life cycles, in addition to the diversity of organisms created in an orchard in situ. The biodiversity generated from plants, insects, or birds in these urban ecosystems can significantly modify a city’s environment and raise people’s level of satisfaction. They become an ideal and potential laboratory for different uses, in addition to a great therapy against virtual reality. Now more than ever, we wonder what really matters and we discover that small things do.

The Comunitat Valenciana count on an urban orchards representation thanks its long horticultural tradition. In recent years and especially in València, despite the substantial loss of fields during its urban growth, there has been a growing interest in urban orchards creation within the city and periphery. Coordinated and promoted, in part, by Red de Huertos Urbanos de València’s efforts (Red de Huertos Urbanos de Valencia, 2012), this network was created in 2012 to encourage first of all the community orchards’ installation in disused urban spaces; the knowledge’s transmission about culture, tradition, and local horticultural biodiversity; aside to provide a social interaction space among interested citizens. This orchards’ management is carried out at the municipal or autonomous level. We present several examples below.

Four city’s urban orchards

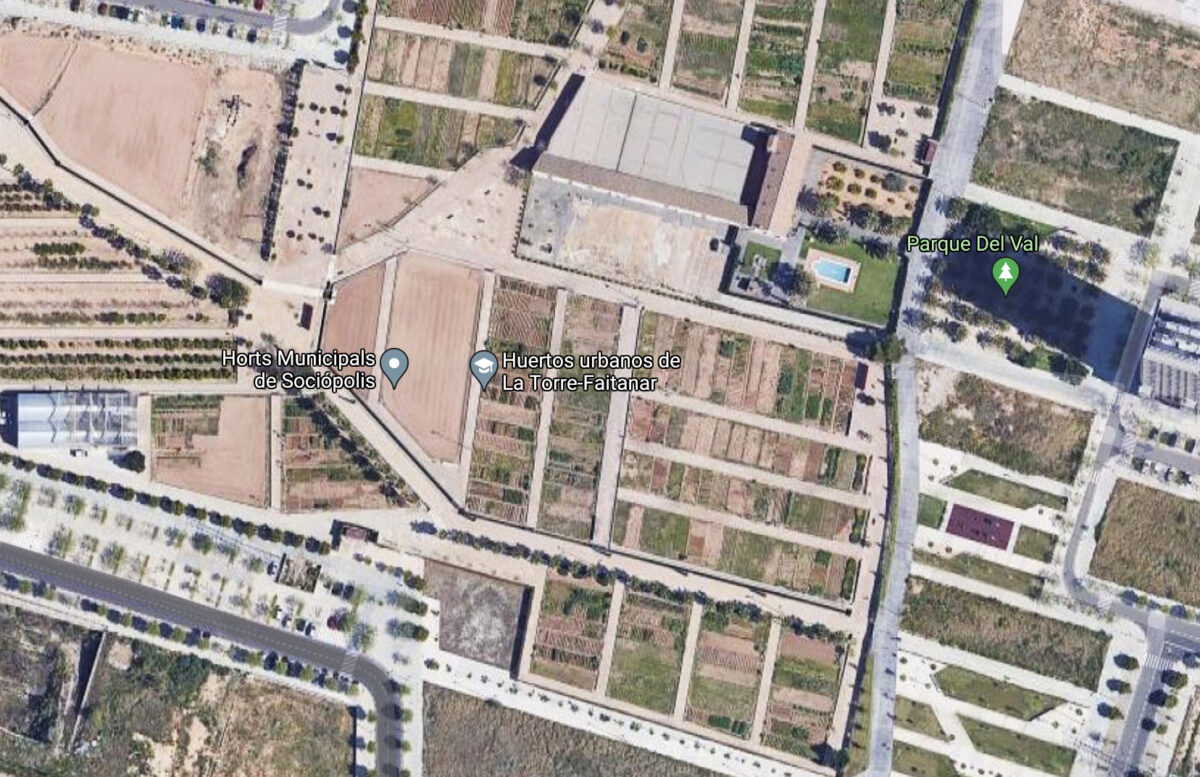

1. Sociòpolis

Located in the south of València, it was initially conceived as an urban project of municipal management that would join housing and green areas generating a neighborhood of sustainable dynamics through parks, gardens, and orchards. Although the economic crisis made it impossible to complete the project, it did not prevent the creation of urban orchards, which is managed by Consell Agrari Municipal since 2012.

As detailed in the Sociòpolis‘ blog (Horts Urbans de la Torre, 2012), during the orchards’ creation, a total of 274 plots were conditioned for agricultural use to protect the rural heritage of the Valencian orchard, promoting citizen participation and contributing to their environmental awareness through various activities, conferences, and courses. These plots, between 40 and 100 meters, are mostly distributed among individuals and associations; all kinds of vegetables, flowers, and aromatic plants are grown in them.

2. Horts de Benimaclet

The Residents’ Association of Benimaclet (Associació de Veïns i Veïnes de Benimaclet, 2014), proposed a recovery initiative for abandoned lands and their conversion into a series of ecological orchards through the Horts veïnals de Benimaclet project. These orchards are managed by the neighbors themselves, according to their specific regulations. The orchards are distributed in 60 plots of between 49 and 70 square meters, in which aromatic plants, fruits, and varied vegetables are grown for household consumption. People involved are committed to following a set of basic rules. In this space of coexistence, neighbors get the chance to better know each other and collaborate in the orchard’s recovery as a key element of their environment, reconnecting with nature and raising awareness about the importance of its protection and conservation.

3. L’Hort de la Botja-Velluters

Located in the València’s heart, Velluters’ district, the Hort de la Botja (Hort de la Botja-Velluters, 2015) was born from the citizen platform Ciutat Vella Batega as a response to educational, therapeutic, and leisure needs, usually identified in the most vulnerable, or at social exclusion risk, groups. In order to address these needs and, at the same time, encourage the urban orchards’ expansion, a diverse group of associations formed by different social groups was brought together to participate in the orchard creation and maintenance (Trip to trip, 2020).

It is a great urban orchard example, despite its recent creation and its limited space, where different techniques of ecological farming have been applied. In this sense, training activities have been planned through workshops supported by other associations with sustainable agriculture’s experience such as Associació del camp a la taula (Del Camp a la taula, 2013) or Sembra en saó (Sembra en saó, 2005). They also carry out in situ composting, supported by Ecologistes en Acció i la Regidoria d’Ecologia Urbana de l’Ajuntament de València. Its environment, surrounded by murals, perfectly combines the art and agriculture tradition rooted in València. It is worth visiting, and we expect the adjacent site to become a horticultural extension as planned.

4. The new Benicalap project

It is currently in a developmental phase. Espai Verd Benicalap (Las Naves, 2020) is managed by several neighborhood associations with the aim of creating a space of cooperation and cohesion in Benicalap. The orchards’ area collects a total of 15 plots of approximately 5 square meters each. The orchards share the land –donated by the Ajuntament de València– with other associations for educational and cultural purposes on the 1,000 square meters plot. Although it is a small dimension enclave, this first initiative can be a shuttle for other projects in this Valencian suburb. Its location is excellent since it poses continuity with the nearby Ronda Norte traditional orchards area of the city.

Spaces to learn how to live in a community

Despite being a booming topic in different parts of the world, there still are just a few research studies on the social and environmental impact, both locally and globally, of urban orchards. At first glance, they are increasingly perceived as a small but manageable tool by the citizenry, really important for fighting against some of the great problems facing today’s society –such as uprooting, isolation, pollution, town planning, and food production management, among others. They are spaces to learn how to live in a community, although managing them can be difficult, it requires communication skills and both group and social coordination.

The urban orchards’ origin is linked to food shortages periods such as the Great Depression or the First and Second World Wars. In recent decades, more than ever, the growth of large cities demands the need for a lifestyle that is more respectful of the environment and human health. Urban orchards are a bet to achieve it. They are small urban spaces where concrete is replaced by green and ground; spaces in which ages are mixed and social roles are diluted. Urban orchards have a number of functions, among them, there is the ecological one, aside from their productive role, since they help to fight air pollution, and climate change, and promote species conservation.

In this way, at the social level, a coexistence and exchange of intergenerational experiences space is created. Its didactic function offers the opportunity to learn through observation, experimentation, and study. It encourages a dynamic, pleasant, and relaxing outdoor leisure, not forgetting its aesthetic function thanks to the natural spaces’ beauty, especially when contrasted in densely populated cities. The changing habits of those who are involved in the orchards’ creations and maintenance tend, indirectly, to reduce their carbon footprint through actions such as local products consumption.

There are studies estimating a net annual average absorption of 1.56 g of carbon dioxide per orchard’s square meter (De la Sota et al. 2018), although more detailed area-based and global studies are needed to assess the urban orchards’ role in addressing climate change. Urban orchards can also become excellent places for different fields of science studies. By focusing on household consumption, they also reduce pollution associated with transport and food waste. Ultimately, participants develop an attitude’s change that, undoubtedly, favors the environment, health, and society, while experiencing that every individual action, however small it may seem, is directed towards a more satisfactory and sustainable world.

Urban agriculture of the world

Little by little, urban orchards have been spreading around the world cities. Some of the internationally best-known ones are the Urban Farm building of Tokyo, with almost 4,000 square meters in the city center; Brooklyn Grange, the largest horticultural space in New York City, where vegetables are produced on a terrace of more than 20,000 square meters; and the DakAkker, the largest urban orchard of Europe, located on an office building’s rood in Rotterdam center, where different varieties of vegetables and melliferous flowers are grown. There also are some underground orchards of plant production, situated in London’s old infrastructure. Ideas for creating green city spaces are constantly emerging.

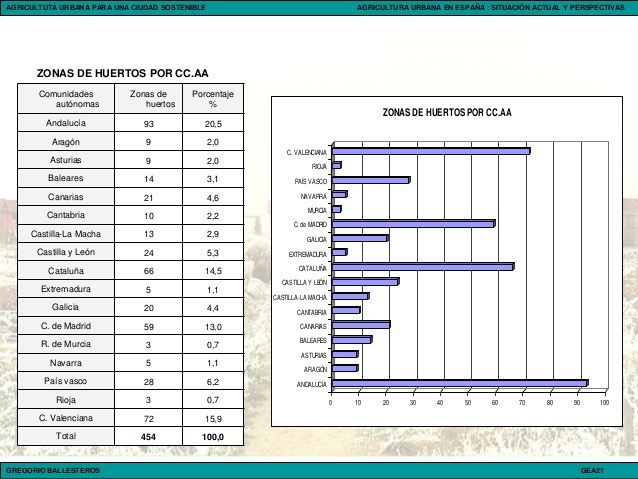

In Spain, due to its long agricultural tradition, more than 900 urban orchards are estimated to be distributed in approximately 25,000 plots in 350 different localities, occupying about 250 hectares, even though there is no official count. There are numerous examples in Madrid, such as Huerto Urbano Comuniatrio de Vicálvaro, 1,000 square meters large, where fruit trees are mainly grown. In Sevilla there is Huerto de Las Moreras, located in Parque de Miraflores, which consists of 175 plots of 150 and 75 meters. In the graph below, it is easily seen that Andalucía’s autonomy is the one holding a greater area of urban orchards, followed by Comunitat Valenciana (Ballesteros, G., 2016).

Bibliografia

De la Sota, C., Puigdueta, I., Álvarez-Gallego, S., Mazorra, J., Cruz, J.L. y Sanz-Cobeña, A. (2018). Huertos urbanos como herramienta para la mitigación del cambio climático. Panel presentado en III Congreso Estatal de Huertos Ecológicos Urbanos y Periurbanos. Valencia. 18-19 de junio.

Pérez, G. y Velázquez, C. (2013). Huerto urbano sostenible. Editorial Mundi-Prensa.

Red de Huertos Urbanos de Valencia. (2012). Información. Facebook. Recuperado de: https://www.facebook.com/reddehuertosurbanosdevalencia/

Simón, M. (2018). Los huertos urbanos a nivel internacional. Comunicación presentada en III Congreso Estatal de Huertos Ecológicos Urbanos y Periurbanos. Valencia. 18-19 de junio.

Vallés, J.M. (2007). El huerto urbano. Manual de cultivo ecológico en balcones y terrazas. Ediciones del Serbal.