Botanist of the month: Raquel Herreros

This week in Espores we have had the pleasure of talking to Raquel Herreros, a passionate botanist with a professional career marked by her dedication to biodiversity conservation. Since childhood, Raquel has shown a great interest in biology, but it was during her university studies that she discovered her passion for botany. Her fascination for flora and her determination to understand and protect the environment have led her to work at the Seed Bank-CIEF, where she develops strategies for the conservation of forest species, and to participate in the AFA project (Atlas and Red Book of Threatened Vascular Flora of Spain).

What attracted you to Botany?

My love for any field related to biology goes back to my childhood. But botany came to occupy a special place when in my second year of my degree I had to make a herbarium for my botany course. I really enjoyed this activity, the whole process was very satisfying: herbalising, pressing, drying, making up the sheets, and so on, and it was especially exciting when I finally got to know the name of the plant I had collected. From the moment I began to recognise more and more plants, the usual landscapes changed, elements that had previously gone unnoticed appeared, adding an extra dose of beauty.

Could you summarise your professional career?

I did an internship at the Jardí Botànic of Valencia in the last year of my degree. Afterwards, I also started my research project there, related to the reproductive biology of plants, with a view to writing my PhD degree. I obtained some grants and financial aid, and so I was initiated into the field of conservation biology of endemic, rare and endangered plants. I then went on to work at the Seed-Bank-CIEF, in a European project related to networked germplasm banks for the first few years, and later in the development of strategies for the conservation of forest species. Eventually, I joined the arboreal heritage team, where I am still working today.

What does your professional day-to-day life consist of?

My day-to-day life is a mixture of field work and office work. We usually go out into the field to inspect protected trees, either as a matter of routine (periodic monitoring is required), or because an alert has been received, or because someone (a local council, a landowner, an interested entity, etc.) requests technical support in relation to a tree specimen. We take measurements, photograph them, inspect their vital, health and structural state, analyse the affections and threats, and finally establish the conservation proposals that we consider most appropriate for the case. In the office, we file and organise all the information gathered, which is essential to know the history of a tree over time. We manage a database with more than 5,000 inventoried trees, some 30,000 photographs and more than 1,500 file folders, among other documents: it is an important volume of information. We also prepare reports, provide advice on tree protection and participate in communication, dissemination and awareness-raising activities.

Are you proud to have been involved in a particular project or discovery?

Yes, I am particularly proud to have participated in the AFA project (Atlas and Red Book of Threatened Vascular Flora of Spain). At the time, almost recently graduated, I did not appreciate its magnitude, but with time I realised that it was a pioneering, ambitious project, in which more than 500 researchers participated, all working systematically with the same rigorous methodology, which would allow for the first time to collect many data related to the geographical distribution of plants and their conditions or threats, which to date were known in broad strokes, and thus reliably assign the category of threat to each plant and thus establish priorities and needs for action. This way of working has served me as a reference in many moments of my professional life.

How important are such projects for society at large?

I believe they are valuable tools for educating society about the importance of biodiversity conservation and the negative impacts of natural habitat loss. They help to raise public awareness of the need to take action to protect the environment and can promote public participation in conservation activities.

Tell us what project you are working on right now

Together with my colleague Ricardo Barberá, I am working on the drafting of a methodological manual for the application of the coefficient of monumentality, an index that estimates the value of a tree specimen by weighting its characteristics according to the different factors that may make it worthy of protection and conservation: age, size or other types of historical, cultural, scientific, recreational or environmental events. This index makes it possible to distinguish specimens of exceptional value from those of notable value and from those of lesser value, and its importance lies in the fact that Valencian legislation allows the former to be declared as “Monumental Trees” and the latter as “Singular Trees”. The aim of writing this manual is to reduce subjectivity, so that consistent results are achieved by different assessors.

Have you met interesting people through your work?

Yes, many, and of very different nationalities: most of them I have met thanks to their participation in various European or trans-Mediterranean projects. I find the confluence between the approach or vision of the work and the different cultures particularly interesting. All these people had one thing in common: an enormous passion for their work.

What is your relationship with the Jardí Botànic and its staff?

The Jardí Botànic is a very special place for me. It was the place where I had my first contact with the professional world, everything seemed exciting, it was a pleasure to be there: I had an exceptional tutor, Jaime Güemes and an excellent colleague, Elena Carrió; there was a great working atmosphere, everyone was willing to help and teach: Elena Estrelles, Xuso Riera, Ana Ibars and Pep Roselló, among others. I had the opportunity to learn a lot. The good atmosphere was completed by other colleagues who, like me, were starting their professional careers with enthusiasm.

How do you think your work has changed over the years?

I often remember the first GPS I got my hands on. As well as being a rather bulky instrument, there was only one for all the staff at the Jardí Botànic, so you had to ask for a turn to use it. Finding a plant in the field, from a bibliographic reference, could be hard work at times; now the locations of plants can be obtained quite accurately even with mobile phones, there is free access to orthophotographs (before, they were a very coveted material to which few had access) and software, all this is easier. Likewise, searching for and accessing scientific articles or other bibliography has become much easier. I think there has been a real explosion of information and resources available.

How would you encourage current biology students to pursue the same career as you? What do they lack?

I think biology students, when they choose to study biology, already know that they will face difficulties in finding a job; I knew that too, and I still chose it. What I want to say is that it is a career where vocation plays a very important role; and that – enthusiasm, motivation – will be fundamental to reach your goals. The road may be long, but it will be worth it.

What does the future hold for botany?

I believe it will be basic in addressing environmental challenges, especially in the current context of climate change and biodiversity loss. Botany will play a crucial role in the conservation of endangered species and the restoration of degraded ecosystems.

Imagine you have as much budget as you want. What would your work be like? What things would you improve?

I would enlarge the work team in order to increase the frequency of visits to the protected trees, and to be able to carry out a greater number of actions for the conservation of the arboreal heritage. With an unlimited budget, it would even be possible to buy the land on which some trees are located, which sometimes are not in the best conditions, and their environment could be significantly improved, allowing for adequate root development or ensuring their water needs. Sometimes it is difficult to reconcile conservation and land use.

Which era of Botany would you have liked to live in and why?

At the time of the great botanical expeditions, around the 18th and 19th centuries. It fascinates me to imagine these intrepid botanists and naturalists, exploring and cataloguing the diversity of plants all over the world, recording detailed information about their habitats, their distribution, their uses… These expeditions played a fundamental role in the exchange of botanical knowledge between different regions; it was a time of discovery, adventure and scientific collaboration that left a huge impact on the understanding of the natural world.

In all these years as a botanist, what is the funniest or most curious situation you have found yourself in?

Once, on the way back from a field trip in the Sierra de Aitana (Mountain range of Aitana), my eyes began to sting and water, and after a while I could hardly see at all. The trainee I had been out with had to take the car to take me to a health centre where I had my eyes washed. I saw blurry for a couple of days, I got quite a shock. I suppose I touched some irritating plant, or it was the fumes of a fixing liquid that I had in the car that day.

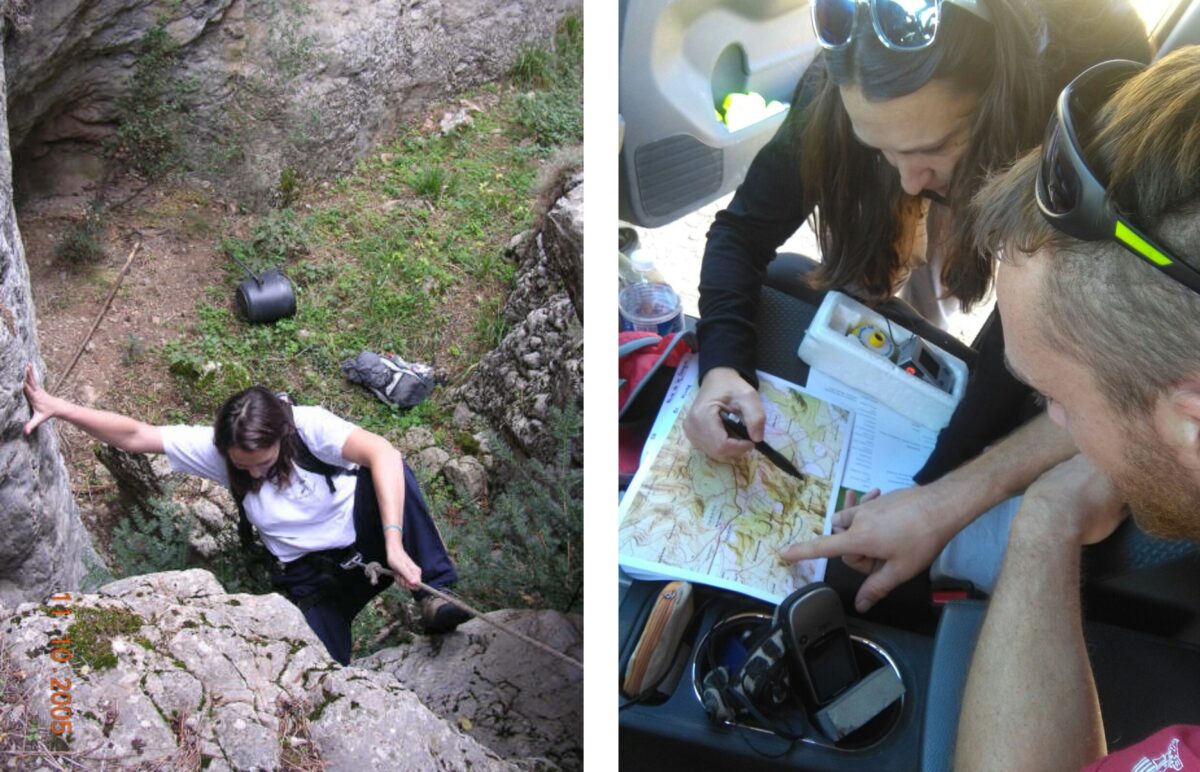

Visit to the Carrasca (holm oak) of Culla during an excursion organised for the Tree of the Year in Spain competition.

Do you work alone or in a team? How does it work like this?

I have always worked in a team; I can’t imagine any other situation. It is enriching to share knowledge and points of view or to be able to discuss doubts, it allows you to learn more and reach solutions more quickly. And then there is the affective part: the mutual support I have had over the years with my colleagues has meant that we have finally become friends.

What tools do you need for your work?

Few and simple: a GPS, a tape measure, a hypsometer and a camera. And the everlasting field notebook where everything is written down; I have not yet found technology that surpasses it.

Do you have a favourite plant or landscape?

Yes, the forests of the Tilio-Acerion forests of ravines, a habitat that is very rare in our territory, and which I got to know late, when I started working at the Seed-Bank-CIEF. I like the freshness they transmit, and the lime trees, mountain elms and hazelnut trees that we can find there, with their bright green colours, seem very beautiful to me. I have been lucky enough to be able to spend a lot of time visiting localities with this type of habitat: first by studying the populations of the most vulnerable species and then, because it was the cornerstone of the LIFE RENAIX EL BOSC project, in which I participated.