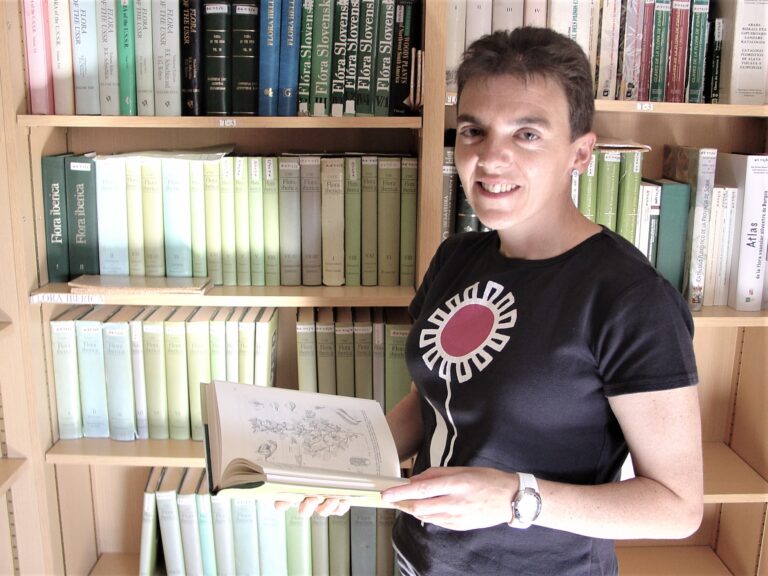

Botanist of the month: Montserrat Martínez

This week we offer an in-depth interview with Montserrat Martínez, researcher and professor at the University of Salamanca, an institution which hosts the researching group on Biodiversity, systematics and vascular plants and fungi preservation which Montserrat leads. Scientist and technical director of the Herbarium and vegetal DNA Biobank Service, her professional career is marked by commitment, teamwork and persistence. Today she will share her career path, travels and other stories with us. Meet our botanist of the month.

What drew you towards Botany?

Ever since I was a little kid I used to walk through the countryside with my parents, especially around mi native Burgos, and during these long walks by foot or bike they would teach me to pay attention to the different forms of life that we could see there, many of them small -ants, butterflies, flowers, goldfinches, etc.- and they would teach me mostly bird and plant names. Little by little, I managed to save enough money to buy binoculars, my first plant guide and a small magnifying glass with which I loved to observe living beings. On the summer I turned 15, after a trip to The Pyrenees, I was so impressed by the meadows where edelweiss grew -which I only knew from ‘Heidi’, ha ha- that I decided to start my own herbarium. That is when my passion for learning to identify and name different types of organisms began. I was always determined about wanting to study Biology -I was given nicknames like ‘bugologist’ for being a ‘bug weirdo’ during high school- and, although I was very interested in birds and reptiles at the beginning of my degree, several teachers helped me discover the many charms of flowering plants: their non-centralised organisation and modular design, their cooperation possibilities with other organisms, their much more flexible ways of multiplication of reproduction than most animals and, given all of this, their huge adaptability in the challenge that it is to endure the difficulties of a static life. Funny enough, I have ended up with mobility problems myself and have also learned to overcome many challenges. When you can’t move, you have to change your way of organisation completely and solve your problems while taking this into account, this sort of… limitation? Or rather couldn’t we see it as an opportunity to force ourselves to think imaginatively about our way of functioning? How could I not find myself constantly pulled towards such a world’s exploration!

How would you summarise your professional career?

I studied Biology at the University of Salamanca and wrote my undergraduate thesis on Botany, more specifically about Pteridophytes in Extremadura. While studying a Masters Degree in Environmental Policy and Management at University Charles III of Madrid, I started developing my doctorate at the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid (Madrid’s Botanical Garden) with a predoctoral scholarship within the project Flora iberica, which was a biosystematics study about the genus Veronica. I feel lucky that I could take part in different research stays at international research centres. During my two stays at Kew Gardens (UK) I could see for myself how the Jodrell laboratory held very interesting seminars on molecular systemics and evolution (Mark W. Chase, one of the main promoters of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group and of the currently well-known phylogenetic classification of Angiospermae, had just joined the laboratory). At the time I was making use of different methodologies for the study of traditional taxonomical characters (pollen, chromosomes, organ morphology, etc.) and I could imagine how big a difficulty it was to establish hypotheses on phylogenetic relationships between comparable species. That being so, I made the most of my stays at Kew and my 3-year-postdoctoral period at University of Viena (Austria) to learn as much as I could about what are known as molecular characters, as well as the different methodologies for phylogenetic reconstruction based on taking into account ‘total evidence’, that is, taking into consideration the information found in DNA sequences, but also traditional characters.

I had already earned my position as an assistant professor at the University of Salamanca shortly before travelling to Viena, and I gathered the requirements for the then known as the new position of Associate Professor before coming back to Spain. And so after the postdoc period back in Salamanca I was able to promote this new position. At the time a research incentive contract allowed me to establish a molecular systematics laboratory, first in a reduced space at the Botany Department, and later within the National DNA Bank’s facilities, and it is in this way that we started with the University of Salamanca’s DNA Biobank, which is centred around wild vegetal species. A path full of work, hope and dedication, the proud tutoring of 10 doctorate theses by greatly competent students, of which I am not only proud but also thankful, since we overcame difficulties and learned together, but yet most of the everyday workload falls on these persevering doctorates and obviously on the not enough recognised technical staff. Almost nobody walks alone in the scientific world, this is about teamwork, looking for complementary skills and promoting synergies that make us grow. And, on top of this, one needs to be brave to a certain degree; in my case this was the case when applying for projects and when obtaining my position as a Full Professor, which I did after sitting for a national qualification exam. This system didn’t last for long and it was lacking here and there, but it offered real promotion prospects to those who were at universities with almost fully-covered public servant positions. Later on, precisely 21 years after I signed that first contract as an assistant professor, I obtained my professorship. Since 2018 I lead the research group on Biodiversity, systematics and vascular plants and fungi preservation at University of Salamanca and I am the technical director of the Herbarium and vegetal DNA Biobank Service.

How is your day-to-day professional life?

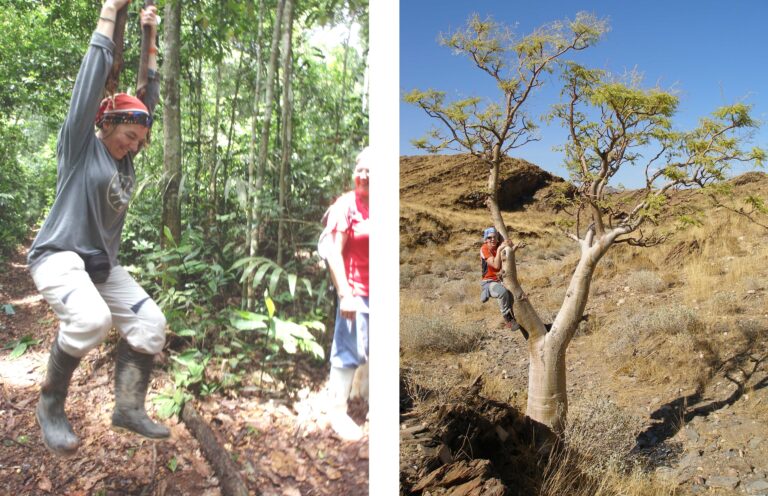

I would say that Botany and Biology are, to put it in a way, part of my constitution. I AM a botanist to the bone, I don’t simply HAVE botany in my life. What I mean by this is that there is no day-to-day professional life for me which is clearly differentiated from some other time when I don’t think and act as a botanist, as a biologist. Some days ago a doctorate said to me «since you’re always thinking, even at the shower, I’ll give you something to think about». And I find it funny that I’m remembering these words now, because that’s just how my day to day is. I could be riding my bike back home from work while thinking about ideas for my next project, watching my nephews and nieces swim while I sketch a way to explain a certain topic to my students in my head, I just can’t close my eyes to plants, even if I’m going for a walk in my free time or visiting, let’s say, Lugo! My day to day is extremely unpredictable and not subdued to a fixed schedule, I’m simply at it all the time. Some parts of it I consider as my real job, most of them having to do with management or bureaucracy and which I try to deal with in a specific time period so that I can have them quickly done. Other parts are a total pleasure to me, and these range from preparing and giving lectures -when it’s a motivating module- to thinking about how to methodologically approach matters related to the development of projects and theses or samplings and botanising campaigns. This last activity is definitely my favourite.

Are you particularly proud about having participated in any special project and/or discovery?

I’m particularly proud about having contributed to the big collective work Flora iberica, which attempts at summarising knowledge on Pteridophytes, Gymnospermae and Angiospermae, which have representation in Peninsular Spain and The Balearic Islands. The project started in 1980 and I joined it in 1994 as I began my doctoral thesis.

How relevant are this kind of projects for society as a whole?

As you can imagine, Flora iberica is a commonly used work by countless professionals and enthusiasts, ranging from agricultural engineers to biologists and environmental science specialists or preservation and garden technicians. Flora iberica is also a tool used in class, in the scientific field for any taxonomic doubt that may arise… with almost 7000 taxa it doesn’t seem unlikely that classifications may blur out a bit in memory, isn’t it? Now, the work is available for online consultation at the Digital Library of the Real Jardín Botánico in Madrid. Although there may be specific taxonomical discussions that only concern certain species, and also in spite of some volumes being maybe a bit outdated, I believe that Flora iberica will remain a reference work for a long time. Its wide range of users and permanence and validity will be the traits that will best show, with time, its relevance for society.

Tell us about your current projects

An ecophysiologist colleague and I are currently leading a project funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation about hybridisation in the Quercus genus. We are particularly interested in the possible adaptative meaning behind hybridisation and introgression in the Quercus faginea × Q. pyrenaica system. We are trying to understand why these evolutionary phenomena take place so frequently in this group and why hybrids aren’t quickly eliminated and rather persist in wide contact areas. Could such processes endow them with genomic and functional flexibility and, perhaps, entail adaptative advantages in contexts of environmental change? Or could it be that hybrids are, with time, selectively eliminated?

At the same time, a colleague from the research institute Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología (Pyrenean Ecology Institute) and I are working on a project with public foundation Fundación Biodiversidad (Biodiversity Foundation) about the endemic genus Petrocoptis. We make use in this case of phylogenomic tools to try to draw clear limits between species, a subject on which there is, at the moment, no consensus and which is relevant for the appropriate categorisation of these species –since many are threatened– and the relationships between them. But we are also interested in other matters that are more explicitly related to preservation, as it is the case with the establishment of germination protocols or the acknowledgement of various parameters such as population’s genetic variability and singularity, among others.

I am also part of a European project, a COST Action (European Cooperation in Science and Technology): “Conserve plants in Europe”, with the aim of establishing connections between scientists and other participants interested in appropriately approaching plant preservation in Europe, as at the moment each country deals with it on their own while plants obviously don’t respond to administrative frontiers.

Apart from those, there are other long-term projects that I keep in mind and are slowly in progress, but which can’t currently count on specific fundings. With limited time, not everything can be dealt with.

How do you think your profession has changed with time?

I was telling you before about how I went from making measurements at first with a binocular magnifying glass, studying chromosomes with an optical microscope or pollen with an electron microscope and so on, to learning about technologies for the study of certain DNA areas. We are now compelled to move from genetics to genomics to try to lay out phylogenetic hypotheses, which means that we have gone from having to deal with reduced data to carrying out massive DNA and environmental data analyses. Now it’s time to learn how to make a model of the different parameter’s evolution through time, of species’ niches, etc. And so, the importance of Bioinformatics in this area is progressively increasing.

In addition to this, on a more personal note, as I have moved further in my professional career, I have experienced a change to my initial interests, first more centred around organisms, then expanded to an interest in processes which produce variation and are of vital importance in evolution, such as hybridisation (with or without polyploidisation). This widening of my interests has led to important changes to my research activity.

How would you assess the field’s current employment situation?

It’s not easy, to be honest. You struggle to get into the university system or the Spanish National Research Council, the scientific career is generally long and strict and, what is worse, not well defined. Moreover, success isn’t always dependant on merits. On the other hand, I find particularly striking how little appreciation the system, to my knowledge at least, shows towards technical staff members, who are key to the development of projects. I don’t really understand either why we the science and technology system makes us waste our time, absurdly most of the times, with administrative difficulties, short deadlines for projects, etc. Such situations drain your excitement for research out little by little, at least at University where we may have other tasks. Obstacle after obstacle, many are the times you may lose (or invest, however you want to see it) your own money on research so that it can be carried out. When you’re very passionate about it, this doesn’t stop you, but some people eventually abandon… and I’m not in favour of it, since researching is among our responsibilities as university professionals. These are known issues, suffered and talked about among all scientists, it’s no discovery of mine.

What’s an essential skill in your profession?

Observation skills, curiosity and clear reasoning are a must, as in any other scientific field.

Would you consider yourself a disciple of any botanist in particular?

Enrique Rico and Ximena Giráldez are definitely botanists I look up to. Both retired now, they used to lecture at University of Salamanca. Apart from my teachers, I consider them as friends, since they didn’t only teach me much of what I know about Botany, but I also see them as extremely generous and humane people, with a passion for this discipline. I still have a blast every time we meet for anything related to the field or in other circumstances. These traits of them are what makes a good teacher, as they were and will always be to me. They may get a bit “angry” with me if they happen to read this, because I know they don’t really like acknowledgment. But I want to stay true to the saying that “gratitude is the sign of noble souls” and, as I owe them much of who I am, both as a botanist and as a person, I can only but publicly acknowledge them, they may as well forgive me about it.

In all your years as a botanist, what is the funniest or most interesting situation you have experienced and may want to share?

We had mixed feelings about having to collect Veronica rosea in Argelia with a bulletproof vest on and surrounded by militaries carrying anti-personnel mine detectors. Up until that point (and others at the Balkans) I hadn’t thought of mine as a risky profession… save my mother from reading this part! It still puzzles me how is it that these militaries let us access such an isolated area at northern Sahara… maybe they pitied us, having reached that far. Their disappointed faces when they saw that what we were looking for was that tiny and almost dried out plant were absolutely priceless and made us laugh.

Are you allergic to any plants? Pollen?

I actually am allergic to Gramineae pollen. In fact, I’ve been admitted to the hospital a couple times as a child, where I would need monitoring and an oxygen supply. Not even that could interfere between my vocation and me haha, although, quite frankly, I’m not particularly keen on Gramineae and I struggle with recognising their species, so this allergy is the perfect excuse to not pay much attention to them! Haha.