Botanist of the month: Manuel B. Crespo

He advocates the dissemination of plant values from the earliest stages of education and optimistically predicts that professionals with a good knowledge of the environment, and of plants, will soon be needed again. Manuel B. Crespo, known as Benito (his middle name) in the botanical world, is a professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resources at the University of Alicante and director of the Botany and Plant Conservation research group at the same university. An enthusiast, in equal parts, of field work, the laboratory and the classroom

What attracted you to Botany?

Like almost all the students who trained in the 1980s, we were attracted to biology thanks to the popularisation work carried out through television programmes such as Blue Planet and Man and the Earth, by Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente. As part of my degree, I became interested in botany. For me it was not something new, because in my family there were always people dedicated to agriculture. And perhaps because of this, plants soon captured my attention… The practice in identifying species, the excursions to collect them and study them in their habitats… Everything contributed to forge in me a growing interest in botany, which eventually became my passion and, in the end, my profession.

Could you summarise your professional career?

I studied Biology at the University of Valencia (class of 1979-1984). I defended my degree thesis in 1985 and obtained my PhD at the same university in 1989, with a study on the flora and vegetation of the Mountain range of Calderona. In 1990 I obtained a position as Assistant in the area of Botany in the Dept. of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resources (dCARN) at the University of Alicante (UA), to later obtain by competitive examination a position as University Professor (1993) and, finally, as University Professor (2002) at the University of Alicante. Over the last thirty years, I have had the good fortune to participate in the training of numerous researchers, who are currently spread across research centres in Europe and America, and I have been involved in training programmes for researchers at the Institute of Biodiversity (CIBIO) of the University of Alicante, of which I was a member until 2018.

My lines of research have always focused on the taxonomy and phylogeny of vascular plants and on the study of vegetation, initially in the Valencian territory and later on in the Mediterranean and elsewhere in the world. I soon realised that an important way of transferring my research to society was to carry out studies on the conservation biology of endemic, rare or endangered flora, for which it was important to know and apply modern and cutting-edge study techniques. I have been principal researcher of numerous projects on the Iberian flora and certain taxonomic groups of the Mediterranean basin. I have had the satisfaction of being the author or co-author of almost 400 research papers published in scientific journals, both in leading international publications and in popular journals.

Are you proud to have been involved in a particular project?

The truth is that I have had the opportunity and the privilege of participating in numerous projects that have modestly led to important advances in the knowledge of the biodiversity of many Mediterranean plant groups; and that is something I am proud of. In particular, I would like to highlight Flora Iberica (the first modern complete flora of the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands), of whose editorial committee I have been a member since 2009, and in which I have been revising and editing genera since 1990. We also participated in Flora endémica, rara o amenazada de la Comunidad Valenciana (“Endemic, rare or threatened flora of the Valencian Community”) (1994); in the Atlas y libro rojo de la flora amenazada de España (“Atlas and red book of the threatened flora o Spain”) (2000-2010), in which we made the records of numerous species with different degrees of threat, almost all of them from the Iberian Mediterranean area, and the Maps and Atlas of the natural and semi-natural habitats of Spain (1994-2004), which was the first inventory and mapping of the types of vegetation in Spain, as part of a European-wide mapping project. But, perhaps because of what it meant at the time, the project I hold most dear is Flora Valentina, dedicated to the vascular flora of the Valencian Community, which began to be published in 2011. I hope it will be revitalised in the coming months. Our flora has a great richness and diversity in the Iberian Peninsula and it is very worthwhile for this study, the first of its kind on our flora, to be completed as soon as possible.

How has your work changed over the years?

The work of a botanist tends to be associated with a romantic ideal of someone who enjoys collecting plants, like someone who takes care of a stamp or coin collection. Nothing could be further from the truth. Today, the botanical researcher is a scientist who focuses his or her activity on the knowledge and conservation of plant diversity, applying the same methodological bases as the botanists of the Enlightenment, but who is also capable of applying the most advanced instrumental techniques and methodologies to understand the evolutionary relationships and genetic variation of plant populations, whether they are the most endangered or the most common in our ecosystems. I myself was confronted with this methodological “transformation” – which, in a way, was also a change of attitude and mentality – in the early 1990s. And, frankly, I do not regret having entered a world that at the time seemed risky and impassable; but which now any student in our classrooms knows and deals with on a daily basis on a regular basis.

What does your professional day-to-day life consist of?

The main task of a university lecturer is divided into two basic tasks. On the one hand, as a teacher, I am responsible for ensuring that my students achieve the training objectives established in each of the subjects I teach (Botany and Conservation Biology) in an optimal way, both through classroom activities (theory classes, seminars, tutorials, etc.) and laboratory and field practices. On the other hand, as head researcher and coordinator of the Botany and Plant Conservation research group at the University of Alicante, my objective is to carry out the research commitments and projects and contracts to which our group has access, as these are the basis for the continuity of the research staff in training in the group. And, finally, there is the outreach of the results through scientific publications, courses, conferences, etc.

Tell us what are you are working on now in your research group

We are currently working on taxonomic diversity and phylogeny of several plant groups worldwide. We have just finished a study on the annual species of blinkers (Biscutella ser. Biscutella) in the Mediterranean basin and the Near East. We are completing new comparative studies on African and European halophytes. We continue to make progress on a revised phylogeny of carnivorous plant species (Pinguicula) in the western Mediterranean… But, perhaps most notably, we are well advanced in an integrated phylogenetic study of bulbous Hyancinthaceae, mainly in southern Africa and the Mediterranean. The truth is that in the last five years we have had the immense good fortune to be able to cover large areas of South Africa, Namibia and Leshoto, describing new genera and species from this surprising and little explored part of the world.

What impact do these types of studies have?

The part of botany that we develop in our research group is what is known as “basic science”. Our discoveries are usually related to the discovery and description of new plants or plant communities, so they rarely have a great media impact. However, the dissemination of our results is the main task of the Botany and Plant Conservation Group at the University of Alicante, which I coordinate. A clear example of the interest in our science is the fact that one of the last species we have described in the Valencian flora, the carnivorous plant Pinguicula saetabensis, has had enormous media coverage, with several radio and television stations (nationally) asking us to report on it. So much so, that this small plant was among the three species that deserved to be included in the programme that Spanish Radio Television (RTVE) annually dedicates to the most relevant species discoveries of 2018. Which is no mean feat! With all this, the importance of our biological diversity is made known and the public gets to know it better and to value its importance.

Outreach is important for you

Outreach, as an intrinsic part of knowledge transfer, is essential nowadays. The outreach of plant values must be part of education plans, from the earliest stages of education. It is no secret that a large part of the planet’s biodiversity is under excessive pressure, which may end up wiping it out forever. But this is not only happening in the so-called “megadiverse areas” of the planet; it is a global process occurring in our everyday environment. Every time a transformation is made that changes land use forever, the genetic diversity of some species is eroded. And when the process is done without proper control and on a large scale, what were once common plants and ecosystems can become, without us realising it, seriously threatened with extinction. We cannot tire of repeating the need for the responsible use and conservation of biological resources in all circumstances. Scientists cannot stand idly by and watch the deterioration of the natural environment. We have a responsibility to collaborate with the different administrations both in carrying out our scientific work and in outreaching our knowledge and making it applicable to the day-to-day life of citizens. Society, through the budgets that the universities receive, partly finances our work, so we are morally obliged to account for what we spend the money we receive. For many years, our group has collaborated with the media (radio, television, audiovisual production companies, etc.) in order to make our flora and landscape known, trying to contribute to the maxim that says: “we must know better, in order to conserve better”.

You are also director of the Herbarium of the University of Alicante (ABH). What is unique about this herbarium?

The official herbarium of the University of Alicante is known internationally by the acronym ABH. It is a collection that was born in the early 1990s, when we joined the University of Alicante, so we can say that it is a young herbarium, if we compare it with other Valencian, Iberian or European herbariums. For this reason, it is not very extensive (it has around 80,000 samples of vascular plants), but we have specialised mainly in halophilic plants (which live in environments with the presence of large quantities of salt), and bulbous plants from all over the world, without forgetting the Mediterranean flora of our immediate surroundings. Despite its youth, we already have a good number of nomenclatural types of plants from several continents, which shows that there is an active plant taxonomy research group associated with the ABH herbarium.

You are part of the Mediterranean Island Specialist Group of the UICN, of the project Flora Iberica, as you told us before, You have been president of the Association of Ibero-Macaronesian Herbaria… What entities would you highlight as indispensable?

I have the utmost respect for all those entities and organisations that are sensitive to the advancement of knowledge through serious and efficient scientific research. Of course, public bodies (ministries, departments, city councils, etc.) are an essential source of support and funding for public universities, such as the one I work for, but we must not forget that private initiative, when it acts with the main objective of promoting development through innovation and knowledge, deserves to be taken into account. The research staff and our groups are the ones who have to offer attractive and internationally competitive lines of work – in our case, the knowledge and conservation of plant diversity -, providing results of interest that satisfy the interests of all parties, but above all the well-being and common interest of society.

Which is the skill you consider as basic to dedicate yourself to Botany?

In Botany, as in other biological disciplines, it is very important to observe carefully and study the data in detail, which, together with a large dose of patience and hard work, will allow us to make deductions as close as possible to the reality we are investigating… Above all, it is necessary not to succumb to discouragement and to continually rethink the initial hypotheses if our results so advise. Nature is stubborn and we must learn to interpret it, based on repeated observations; we must never pretend that what we see – or what we think we see – must conform to what we want to happen or what we think should happen. That is not science.

Do you like working alone or as part of a team?

Because of the way I understand our science, I cannot conceive of working alone. It is true that the latest technological advances – especially the Internet – allow us to have, in a matter of milliseconds, a huge amount of information that is even difficult to process, but which gives us a great deal of autonomy. However, I have always liked to share my knowledge with others, both with my colleagues and with my collaborators; to work side by side. That Iberian aphorism that says “four eyes see more than two”, applied to our discipline, leads us to reflect on something fundamental in any discipline of knowledge: the discussion of results, if shared, ends up offering more solid conclusions, more difficult to refute. My experience allows me to state this categorically. Teamwork requires full trust and loyalty among the members of the group, which makes it possible to distribute tasks of responsibility and makes each member (within the scope of their responsibilities) feel that the results are their own, shared by everyone. Sometimes, the heads of research teams are not able to discharge this responsibility adequately and this can lead to tensions or work overload, causing the results to be less than optimal and the teams to suffer.

What tools do you need for your work?

Since I joined the University of Alicante, I have tried to ensure that our team combines classical botanical work (collecting material and taking data in the field, studying herbarium samples, drawing up inventories, etc.) with modern laboratory techniques (DNA sequencing, molecular phylogenies, studies of population genetic variation, etc.). This means that we need enough budgets to cover both the cost of herborisation campaigns to expand the ABH collection and visits to the major herbaria in Europe, as well as the expenses of a molecular biology laboratory. So far we are being efficient in these aspects and we cannot complain, because the many works we have underway – or in the pipeline – are coming along satisfactorily and we are covering our budgetary needs. However, we must continue to remind public administrations that it is time to devote the necessary resources to science so that our country and our society are not dependent on technological advances and knowledge generated by third countries. Otherwise, the scientific potential we have in our universities will slip through our fingers and we will lose all the effort dedicated to training young researchers. For our part, we work every day to maintain the prestige of Spanish botanical science at the highest possible level.

Do you think your work allows you to learn about topics unrelated to Botany?

Fortunately, I am not only a botanist, but also a biologist, and I am passionate about all things related to this science. In recent years, we have collaborated closely with entomologist colleagues within the European project FlyHigh of the Marie Skłodowska Curie (MSCA) – Horizon 2020 programme on innovation and researcher mobility (RISE), funded by the European Commission. This recently completed project involved researchers and companies from Finland, Serbia, South Africa and Spain. One of the objectives was to study the feasibility of using larval stages of certain insects (mainly diptera and syrphids) as a source of protein for animal consumption. Although our task was basically focused on identifying the plants in whose bulbs the larvae of some of these insects grow, the experience of observing the species in their natural environment in southern Africa and learning about their relationships with insects that, depending on the phases of their life cycle, act as predators or pollinators, has been very positive… I would even say surprisingly enriching.

What is your relationship with the Jardí Botànic of the University of Valencia?

For many years I have had a strong personal bond with the Jardí Botànic, especially since the time it was remodelled by Prof. Manuel Costa. I have always felt at home here, like one of the family. For many academic years, our students from the University of Alicante have come to visit its facilities to learn about the study and conservation of endangered Valencian flora that is carried out here. On the other hand, I maintain friendship and professional ties with many of its members, who were once my teachers or classmates who I shared a desk in class with during our student days. This is the case of the current director of the Jardí Botànic, Prof. Jaime Güemes, who I have always maintained a very special relationship with and have had the good fortune to share many far-reaching research projects.

Do you consider yourself a disciple of any particular botanist?

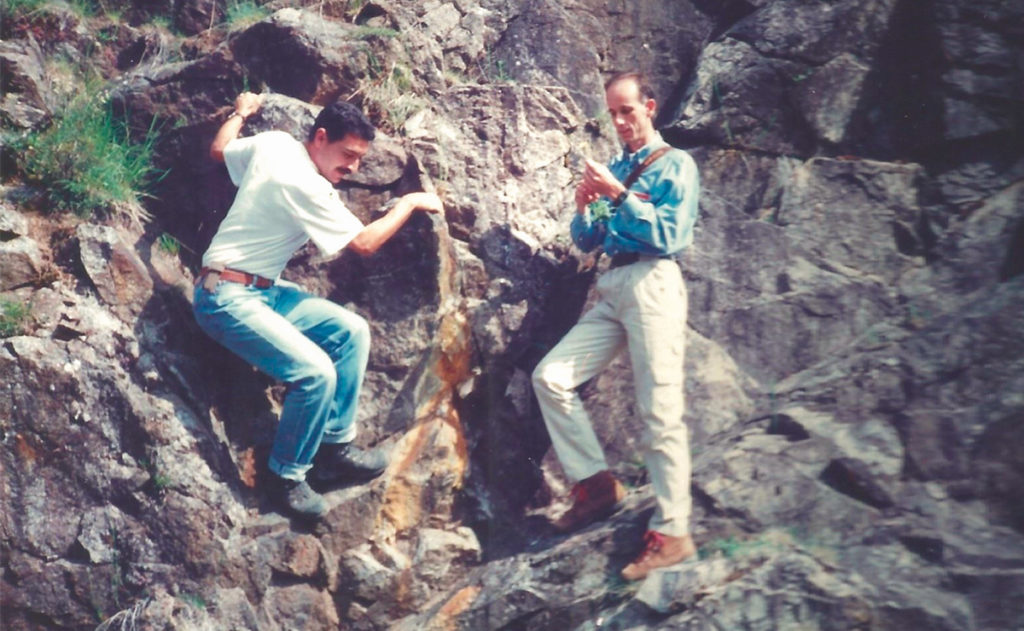

Many people have been involved in my training, both directly and indirectly, through their teachings and writings. But two botanists from the University of Valencia are what I consider to be my true teachers, from whom I have learned much of what I know today and whose influence has been decisive in my professional development. On the one hand, Prof. Gonzalo Mateo Sanz was the one who introduced me to Botany when I was a Biology student in the early 1980s and, from the very beginning, he guided my career until I reached my PhD degree. And we are still working together. On the other hand, Prof. Manuel Costa Talens reached out to me and helped me learn more about the science of vegetation and landscape when I was finishing my doctoral thesis in the late 1980s. He always offered me selflessly his help when I asked for it and today I can proudly say that he considered me one of his disciples. Both trusted me at different times in my professional life and I have great admiration and respect for them and their work. We maintain a sincere friendship, to which I add a deep sense of gratitude.

Which era of Botany would you have liked to live in and why?

The truth is that I am glad to be a product of my time and to have seen first-hand the enormous advances and deep transformation that Botany as a science has undergone in recent decades. I feel privileged for this and I would not change these experiences. But if I had to choose an earlier period, I think I would definitely go back to the Enlightenment: the period between the 18th and 19th centuries. A turbulent but exciting time, it is for me the period in which the most important advances took place in Europe, both in the social and scientific spheres, which led Botany to become the modern science that has survived to the present day. France and its immediate surroundings were, at that time, the nerve centre of knowledge. The great milestones in the study of plants, in their description, their systematic approach and even the first solid ideas that nothing was immutable arose in those prodigious decades for knowledge. Figures like Lamarck, so unjustly reviled by some, or De Candolle, authors of monumental botanical works that changed the state of things on a global scale… Or in our country Cavanilles or Lagasca, who had to face the incomprehension of their contemporaries… All of them great botanists who, without needing great material means (if we compare it to our current technology), wrote works of such magnitude and impact that will last forever. It was a time that I really would not have minded living through… And, for sure, I would have lived through it intensely.

What future awaits Botany?

I am an optimistic person by nature, so I cannot – and, moreover, I refuse to – predict a bleak future for our science. When I was a biology student, nobody believed in our science; now biologists are a necessary part of public administrations, they are professionals who study the environment, who run biological analysis laboratories, who are integrated into multidisciplinary teams in hospitals, research centres, etc. This means that, in a society as swinging as ours, there will soon be a demand for good professionals with a good knowledge of the environment and its components. And this must once again lead us to rethink the focus of our degrees and the training of our graduates in order to satisfy social demands, which are increasingly aware of growing environmental problems… Moreover, as strange as it may seem, there is still a lot to be studied before we know our plants well. And, without any doubt, there is still much more to be done in large areas of the world that are not necessarily the great tropical rainforests. Experience teaches us that we should not be gate-keepers and that our projects must be ambitious in their objectives and scope.