Modern Ikebana: the nageire style

Victoria Encinas brings us a new article on ikebana, an aesthetic creation, originally from Japan, which manages to transmit the essence of what is alive to those who contemplate it. The author, with a long career in the practice of this artistic discipline, describes the singularities of the nageire style, a form of ikebana made in cylindrical, simple, ceramic vessels, which gather beautiful textures, finishes and nuanced colours and which evokes nature, its past, present and future.

Nageire is a very popular style of ikebana, not only in Japan, as it is practised by amateurs all over the world. Although its origin is ancient, the updated form of nageire is one of the first lessons that students in international ikebana schools usually learn because of its relative simplicity.

The term nageireru, alludes to the idea of “freely disposing” and could be translated in this way. The nageire style updates the classic asymmetrical order, whose canon is shoka, interpreting it in a less strict, more flexible and relaxed way. However, even if its spirit is rather naturalistic… it has its rules! Even in the most fluid and informal compositions, ikebana never renounces the underlying morphological scheme, trying to understand and express the natural order. This aesthetic interest, in the emotionality of traditional Japanese culture, is the union of philosophical concepts and artistic precepts.

(Before going on, I would like to say, in parenthesis, that the pronunciation in Spanish and Valencian is “nagueire”, with the soft “g” sound, not the “j” sound).

The uniqueness of the Nageire style

This form of ikebana is made on upright, usually cylindrical, plain, ceramic vessels. They often contain beautifully nuanced textures, finishes and colours, but do not usually have figurative or curvilinear forms.

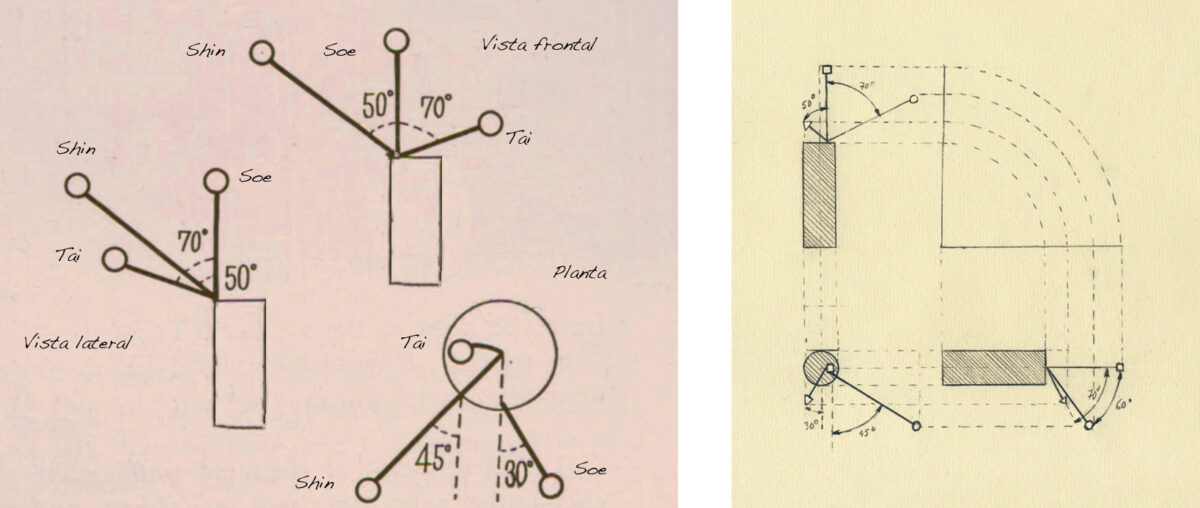

Like moribana, a style discussed in the chapter “Ikebana: the natural canon”, it is based on the structure of three main branches, or yakueda: shin, soe, tai, which form a scalene triangle. This asymmetry suggests the evolution of plant growth and evokes life in its dynamics. The two strongest leading branches (shin and soe) generally come from shrubs or trees and the third (tai) is shorter but showy, usually one or more flowers. A few smaller twigs or small flowers make up the ashirai, a complement that is sometimes used to add nuances, detracting from the dryness of the structure, providing a contrast in colour or shape, making the arrangement more enjoyable.

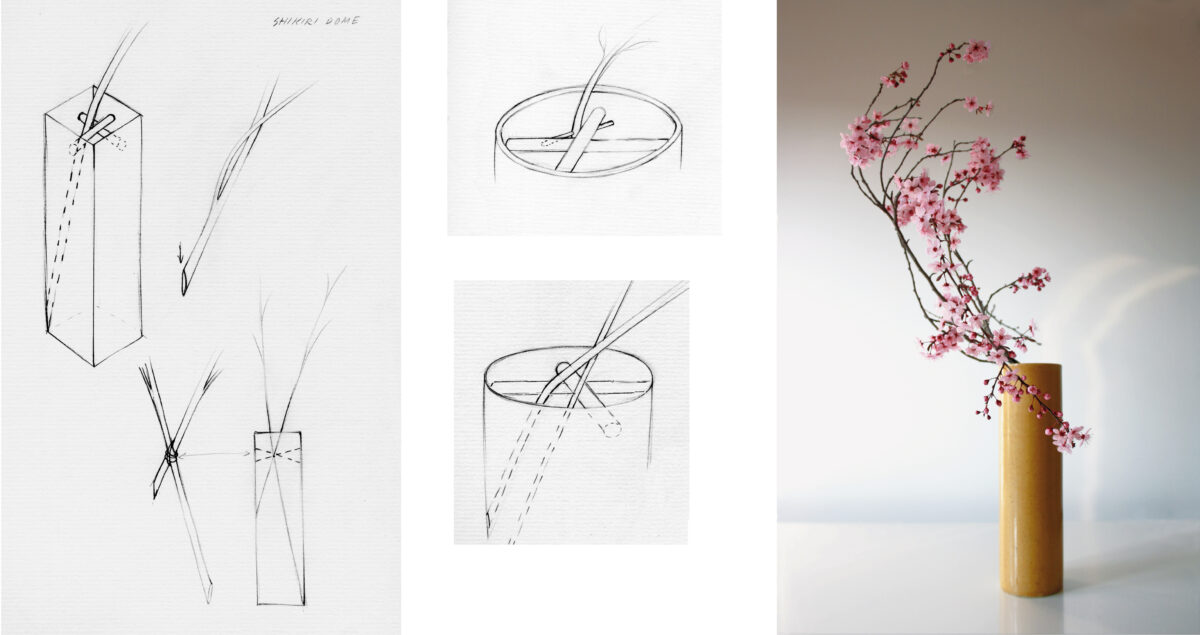

A peculiarity of nageire-style arrangements is that the plants seem to emerge from the side of the lip of the vessel, as if from the surface of the water. They do not rise vigorously from the centre of the vessel, as in the formal styles (shoka, rikka), but are held more gently, with a certain ‘carelessness’. The tall ceramic vessels in which it is composed are usually about eight or ten centimetres in diameter by about twenty-five or thirty centimetres in height, and the arrangement is born a few centimetres inside the mouth of the vessel, always in one quadrant of the vessel, leaving the other three free.

A nageire arrangement does not resemble a Western “flower vase”, although both are the desire for the presence of flowers in human life… In the formal aspect, the flowers and branches of a Western bouquet are introduced more or less homogeneously occupying the whole opening and generally reaching to touch the bottom of the vessel, on which they rest; or else gathered by the inner walls of the vessel and creating a mass in which the flowers proliferate in all directions compacting into dense areas of colour. But in a nageire-style ikebana the arrangement is almost empty; it is suspended, like an Alexander Calder mobile, somehow floating; very aerial. The branches draw this emptiness, like lines, defining the space that inhabits this asymmetrical triangle: few materials and a lot of space for a simple drawing.

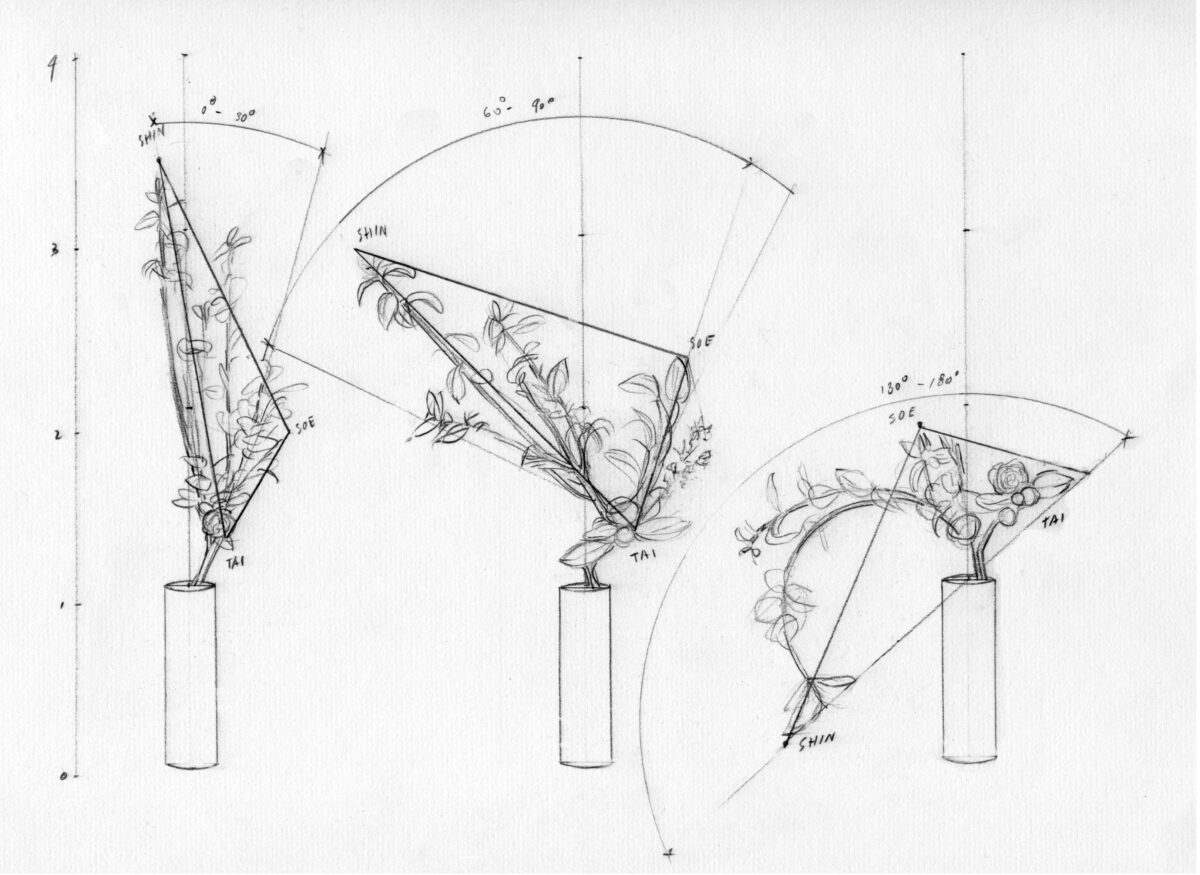

Compositions and angles

a) Vertical typology, whose branches, seen frontally, are hardly separated from the perpendicular axis with respect to the surface of the water; the complete arrangement then develops in an approximate vector from 0° to 30°. It is called Choku–tai or Sugu-tai by some schools.

b) Oblique typology, when the branches are concentrated approximately between 60° and 90°. The arrangement is in the form of a slanting composition, either on one side only or opening out to both sides. It is also called Sha-tai by some schools.

c) Descending typology, or ‘cascading’, is the arrangement that rises slightly at its base to exceed the horizontal and then falls downwards from the mouth of the vessel. The branches take on a curved arrangement, drooping down from their source, at very open angles. Some schools call it Sui-tai.

In the example of the three camellia arrangements (above, photographs) it was possible to make all three arrangements with the same plant, because the adaptability of the camellia stems is very great, which makes it a highly valued species for the versatility of its branches, as well as for the splendid early flowers and the resistance of its leaves.

The names may vary and diversify into sub-genres, but the schools of ikebana all agree on the essentials. And what is essential, by the way, is not so much the technique, but learning to look at nature from an aesthetic and respectful point of view. In Western ikebana associations, teachers from different schools have no difficulty in combining their knowledge and techniques.

The composition of the branches should be supported in the way they would be found in nature, offering their leaf bundles to the sunlight, emerging and unfolding as they would by their natural growth. The arrangement can be oriented to the right or to the left (hongatte and gyakugatte), always facing towards the source of light where it is to be placed, and also towards the observer’s point of view. Although nageire is now performed and arranged in contemporary spaces, it still retains its original appearance.

The original place where the arrangements were placed in the traditional Japanese house as well as in the sukiya (teahouse) was the tokonoma, a very empty space with a wooden platform-base and side lighting. Depending on which side of the tokonoma the light came in, the arrangement had to “face” towards that area.

The nageire technique

For the training of the students, abstract diagrams are used; and of course, the irreplaceable presence of the teacher, who often carries out the proposed arrangement live in each class.

The simplified drawings, which vary little according to the different schools, generally show three dimensions: 1) the lines in space from a bird’s eye or plan view, 2) the front elevation of the arrangement, and 3) the side view, representing the angles at which it is to be laid out. It is a spatial tour in the three directions of space: height, width and depth.

These diagrams are indicative and serve to guide the composition. Depending on the character of the branches, the most suitable inclination of the arrangement is taken into account. Finally, it is the shape of the branch itself that draws in the space.

Technically speaking, to make these arrangements, a curious and effective fastening system is used, which consists of inserting two small pieces of woody twigs, intertwined and arranged horizontally, under pressure, forming a cross between the inner walls of the vessel a few centimetres from the mouth of the vessel. They must be firmly fastened, and they do so thanks to their own tension and strength. The solidity of the support is tested by lifting the water-filled vessel, holding it only by this Greek cross of twigs, and grasping it with the fingers. Any flowers or stems that are subsequently placed – being accumulated in only one of the four sections – will be firmly supported and their position will not oscillate.

In this way, the source of each branch or flower appears to rise from the surface of the water and this gives lightness to the arrangement. It is important to insist that the birth of the whole arrangement is inserted in only one of the quadrants, thus achieving a sensation of autonomy of the plants, which seem to be born or sprout as if by their own vital force emerging from a zone of origin. This concept is key to the aesthetics of ikebana: the flowers and branches are alive. The arrangements must be able to transmit this vigorous force of nature.

The base, or the birth of the plants, is a very important part of the arrangement. It defines the way the branches develop in space, their expansive evolution. This base of the arrangement is called mizugiwa.

Just as the mizugiwa of shoka and rikka is very firm, upright and meticulously aligned, the mizugiwa of nagueire and moribana is relaxed and organic. At the birth of the nageire and moribana arrangements, branches can cross each other, lean against each other, accumulate without a strict order, even be hidden by smaller leaves, spontaneously… something that does not happen in the formalist arrangements, shoka and rikka, whose cleanliness and neatness is perfect.

Expression and creation

Returning to the beginning of this article, the term Negeireru alludes, as we have already noted, to the idea of “free disposal”. The vegetables emerge from the pot without implements or accessories to correct or fix their shape. Nevertheless… so many indications, aren’t they? This is how it is; the exercise of entering into any style or school of ikebana, even the most modern and uninhibited, entails studying and practising strenuous attempts to decode and recode, from the plastic values, the organic order implicit in the form of the plants.

It is common for the arts to achieve a natural and sensitive appearance by quite mental or artificial means. This tendency towards regulation in ikebana, which discourages some Western students, should be interpreted as a guide, an openness to observation. As in learning to dance or sing, etc., discipline in rehearsal is the necessary support for the moment of inspiration, the moment when, in ikebana, we find that particularly expressive and moving branch with which we make an arrangement. With time and practice, what we learn as an abstract order becomes a habit of the eye, almost a built-in and internalised instinct that guides us in the correct assessment of natural proportions, and which will make our arrangements “naturally” beautiful. And our walks in nature something even more meaningful.

Bibliografia

«Ikebana. A new Illustrated Guide to Mastery» Wafu Teshigahara. Kodansha International, Tokyo, New York, 1988

«Ikebana. A practical & philosophical guide to japanese flower arrangement» Estella Coe. Edited by Mary L. Stewart. Octopus, 1984

The most didactic literature on ikebana in Western languages was published between the 1960s and 1980s. Nowadays, schools publish their own manuals; the popular publishers are more focused on the striking visual image than on teaching.