The botja orchard, one more step towards a green Valencia

Changes and new ways of understanding urban customs are the key to the sustainable development of large cities and, in the case of our city, the agricultural spirit of the citizens has been making a strong comeback in recent years. Thus, urban orchards are positioned as an alternative to asphalt that, thanks to citizen mobilisation, is being consolidated in the different neighbourhoods of Valencia, even in the historic centre of the city, as is the case of the botja orchard, which has become a new green space in which to build community and connect with our culture and our land.

The botja orchard and its neighbourhood network

On Friday 10 February, the JardÍ Botànichosted the screening of the short documentary De pies en tierra, directed by Bebé Pérez and Malena Sessano, which tells the story of the botja garden. An abandoned space in the heart of the Velluters neighbourhood, just 500 metres from the JardÍ Botànic, which has become one more step in the green fabric of the city of Valencia.

As time goes by, society’s preferences evolve and, fortunately, we always find certain pioneers who are at the forefront of these changes. This is the case of this urban orchard, another success of the neighbourhood of Velluters through the “Ciutat Vella Batega” platform, by now the main social and cultural engine of a very central area, altered and invaded by tourism and real estate speculation.

Despite the fact that this neighbourhood has a large number of pedestrian streets, where the mobility of cars is very limited, it is asphalt and not nature that often permeates these spaces, resulting in a significant lack of green areas. Areas in which to connect with nature, the land and what we eat, which also become meeting places, where we can create a neighbourhood identity and generate a neighbourhood network.

Motivated by the hope for change, other associations joined the platform, such as the Velluters Day Centre for the Physically Disabled, the Itaka Escolapios-Amaltea Foundation and the Juana María Residence, among others. Thus, together, they demanded the management of this space through mobilisations and lobbying, achieving that the Valencia City Council invested an amount of 45,000 € to enable the site to be used for cultivation, as a new green spot in the neighbourhood and also with the aim of supplying educational, social and cultural needs of its neighbours.

The objective of these platforms will increase in the coming years, as they intend to ask for a second concession of a plot of land near the orchard, which they want to use for social and sporting activities. But this time with a pretext and security given by the results obtained in recent years in the Hort project, which has generated what they call “the Loca’s revolt”.

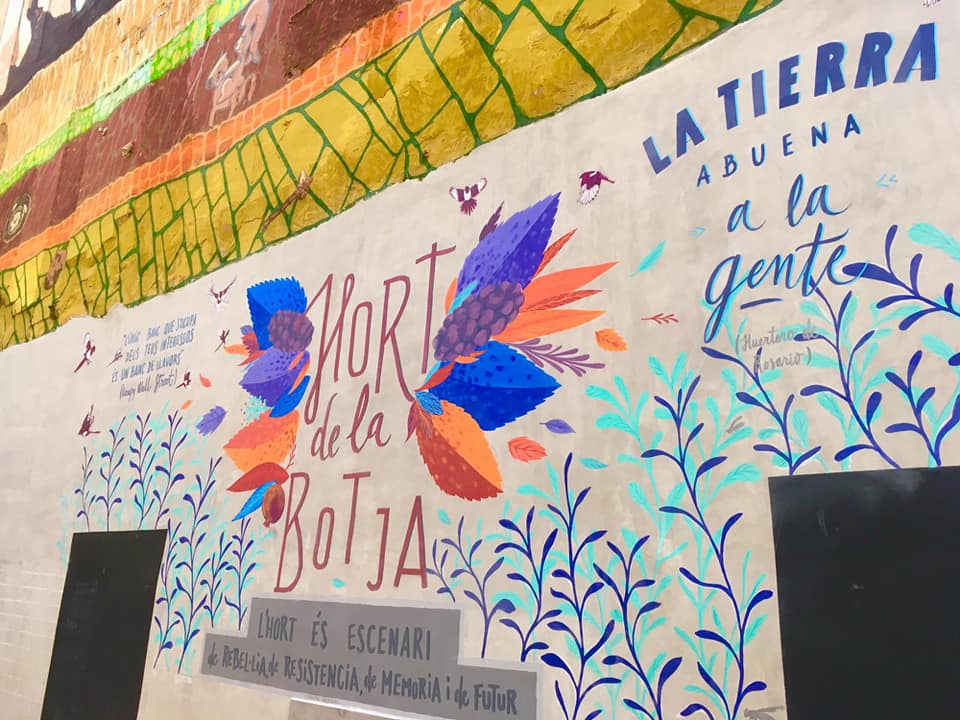

A square named ‘botja’ in honour of a plant. A plant species closely linked to the traditional production of silk, which once characterised the Velluters neighbourhood, and with which the silkworm’s cocoon was raised. Moreover, in the specific case of this space, it was an abandoned plot of land, owned by the Generalitat, which formerly served as an orchard for the Valencia Carpenters’ Guild. These were times when agricultural activity and craftsmanship were very much in evidence in the neighbourhood, and which they also wanted to reclaim by means of urban art on the adjoining walls of the botja orchard. Therefore, it is also a question of historical memory and of gradually reclaiming land from the buildings to be used for what the citizens really need.

Other orchards that add up

Apart from the successful case of the botja orchard, there is a growing number of urban orchards in the city of Valencia. All these projects start from very similar points, in their beginnings, management and needs, but what stands out in most of them is the union of the neighbourhood network, which reclaims spaces in disuse or with unsatisfactory planning in order to reconvert them into spaces for meeting and contact with nature.

One of the best known is the case of Benimaclet. In 2014, the neighbourhood’s residents’ associations proposed an initiative for the recovery of abandoned plots of land that are now a benchmark. Its management is based on the organisation of the space into different plots where participants grow a variety of vegetables, committing themselves to basic rules of coexistence and community.

Very similar is the case of the Benicalap allotments, where the understanding of the different neighbourhood associations has also made it possible to generate a space for cooperation and cohesion in a peripheral neighbourhood. Other associations are also involved in this project for educational and cultural purposes. This is a positive and growing trend that more and more neighbourhoods in the city are joining, as is the case of La Torre, Patraix or Malilla, and also beyond the capital in the towns of Paiporta, Torrent or Alaquàs, among others.

On the other hand, urban orchards can play an important role in environmental education, as a powerful teaching tool with which to carry out practical actions that facilitate the understanding of what is explained in textbooks: where the fruit and vegetables we eat come from, understanding the seasons, or what the life cycle of a vegetable is. In addition, a link with the land and a greater awareness of the importance of zero-kilometre trade is generated from an early age.

Currently, some of these educational initiatives are already in place in a good number of educational centres in the city of Valencia, which have set up areas for growing crops, either within the teaching space or on land provided by the City Council. This is the case of the nursery school El Trenet, which managed to create a school orchard in the Patraix neighbourhood, through the participatory budget initiative decidimVLC.

A magnificent opportunity to feel the heartbeat of the earth in the heart of the city, for children to acquire ecological awareness through experience, for them to learn to take care of nature and to be sensitive and empathetic with the environment, to work cooperatively for the common good, and to savour the fruit of their dedication and value that of the thousands of farmers who every day nourish us with the best treasures of the land. Let’s make orchards of the senses, a school of culture and a pantry of life lived and life to live, let’s make orchards out of the plots, let’s make the plots places of meeting and exchange, of illusion and shared effort! This is how El Trenet defended this project that it now manages together with the Risitas nursery school and the Hermes school and which provides the children with a space for experimentation in the form of flavours, colours, aromas and sensations, which undoubtedly enrich the teaching.

To a certain extent, all these activities allow us to get closer to nature and our horticultural culture in the city, where the connection with the land and its stimuli is practically unthinkable, offering the opportunity to escape from the concrete of the neighbourhood.

The city and its new needs

In view of this drive to create urban orchards, it is important that they are not interpreted in isolation as green spots within neighbourhoods. Orchards, parks, gardens and trees all add up to avoid fragmentation and create biological corridors to promote biodiversity and connect the city with its surroundings, as the urban architect Carles Dolç points out.

In this case, Valencia has certain advantages for achieving these ecological objectives, such as the 13 km long Old Turia Riverbed Garden, a belt of orchards and the Albufera Natural Park, just a few kilometres from the capital. It also has large parks located in the interior of the city, such as the Viveros Gardens, La Rambleta, Benicalap Park, Marxalenes Park, the Central Park, the Cabecera Park and the JardÍ Botànic of the University of Valencia. The latter, together with the Hesperides Garden and the new ‘Bardissa’ project inspired by the orchard, which will be projected on the controversial Jesuit site, will create a new inspiring green corner in the city.

In addition to all this, almost 3,000 trees have been planted in the streets of the capital, which have reinforced and extended what already existed, in an attempt to connect these spaces of nature and create an authentic green network. A living network that must be cared for and promoted for the numerous benefits it brings, and which is in accordance and harmony with Valencia’s candidacy as European Green Capital for 2024. The aim of this project is to increase the city’s natural spaces and its green personality. Cities must be covered in green if we want them to be able to withstand what is coming in 10 or 15 years’ time,” said Beatriz Gascó.

Nature and biodiversity are one of the key indicators for achieving sustainable and resilient cities in the face of climate change, as indicated in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 on “sustainable cities and communities”. These SDGs were established by the United Nations as part of the 2030 Agenda, as a universal call to action, from the local to the global, to protect our planet, end poverty and improve the lives and prospects of people around the world by that date.

Faced with a global crisis, society today is at a turning point where it is forced to change its habits in order to improve living conditions and its environment. An environment in which more and more transformations caused by anthropogenic activities are becoming evident, affecting all citizens.

A situation that is even more evident in the concrete nuclei, where life is directly conditioned by immediacy and consumerism, increasing uncertainties about the environment. The multitude needs to move fast, individually and effectively, as wasting time is penalised, and “junk” food, frozen food or prepared meals in the supermarket are the most commonly used solutions.

In this sense, the creation of urban orchards is not only a green space that improves the environmental quality of the surroundings, but also makes possible areas where we can stop and adjust to the rhythms of nature, and also self-sufficiency, where food can be consumed locally and also destined to needy people in the neighbourhood in line with SDG 2 “zero hunger” and SDG 12 on “responsible consumption”.

Valencia is unique for carrying out these actions, due to its geographical and meteorological conditions. Moreover, it is one of the few European cities that is surrounded by orchards. This heritage has suffered great destruction and damage as a result of urban expansion, and now more than ever it is necessary to protect it. Acts such as these of deurbanisation, increased ecological awareness and environmental valuation, contribute to strengthening the city-orchard symbiosis that characterises our city and which is now being proposed as a model for the future.

On the other hand, we also find other types of benefits, related to mental health, to be able to enjoy outdoor spaces, in contact with nature and with other people, in relation to SDG 3 on “health and well-being”. This is a very hot topic in the pre-pandemic times in which we live. Carrying out collective activity to maintain these projects generates synergies between neighbours, increasing care among the participants of the space and a substantial improvement in the quality of the neighbourhood and its neighbourhood network.

The La Loca orchard materialises the conflict that exists in the neoliberal city between use value and exchange value, says Hernán Fioravanti. Increasing green spaces and their coexistence with society facilitates the symbiosis of asphalt and the green of the streets. Therefore, the new trend of deurbanisation and disarmament of neoliberal infrastructures, through the strength of the neighbourhood and correct policies, will build a path that will allow us to see the light again in the care of our land.

Thus, these pioneers open a new trend, not only of agricultural activities, but of awareness, change and new ways of facing the reality and value of the environment, of our food and of living in community.