Botanist of the month: Simón Fos

PhD in Biological Sciences from the University of València, he has a special interest in inventorying and spreading awareness of Valencian lichen flora. After a stage in his career linked to research and teaching, Simón Fos started a new chapter working on technical assistance in management and conservation of rare, endemic or endangered flora and natural habitats. But this botanist, passionate about science dissemination, has never abandoned those increasingly unknown organisms that caught his attention years ago: lichens.

What attracted you to botany?

Plants are the most obvious structural element in ecosystems. Vegetal communities shape landscapes in response to the dominant environmental variables, climate, soils, etc., and, naturally, human influence. And in turn, these communities determine the rest of organisms that make up the global ecosystem. Since I was little, I was sure I wanted to become a biologist, and my preferences leaned towards ornithology when I started the degree, but after my undergraduate studies, I realized the impact of flora on wildlife, so I decided to change my initial priorities and delve into the study and knowledge of plants.

Could you summarise your professional career?

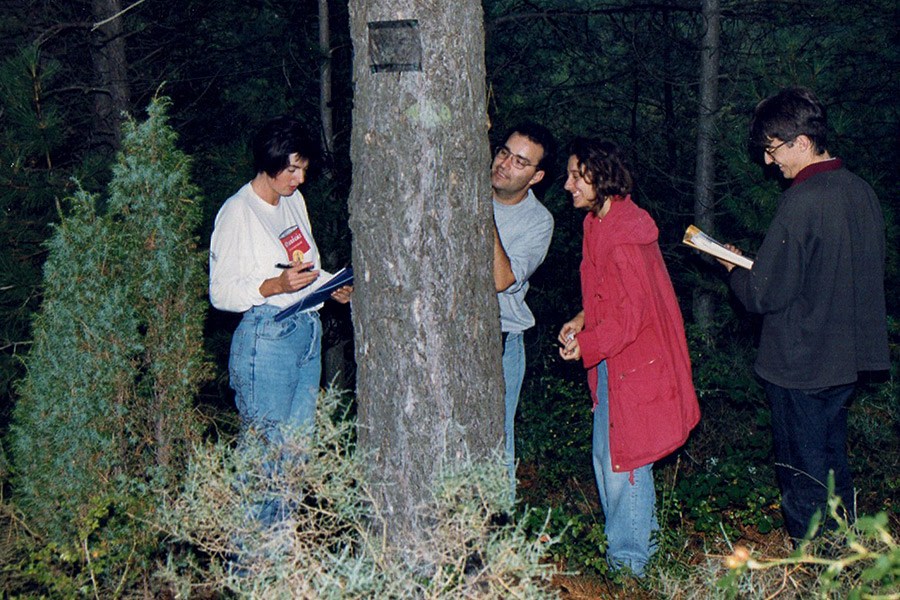

My professional activity could be divided into two main stages. The first one was carried out in the Faculty of Biological Sciences of the University of València, where I had trained to be a researcher with a grant from the Ministry to develop an original and quite particular project with lichen bioindicators, under the guidance of Dr Eva Barreno. Throughout this first period, I worked in different research projects developed by the team I had joined: lichen flora of the Iberian moorlands, in the Muniellos Reserve; air quality monitoring in the regions of Els Ports and El Maestrat, and of the Font Roja oak-grove and the outskirts of Alcoi by using lichen bioindicators, as well as in the pinewoods in Tenerife and other islands, in this case, evaluating and quantifying the damage caused by the pollutants on the Canary Island pine needles. I also conducted on my own several studies about the lichen flora of different areas in the Region of Valencia. In my opinion, floristic projects are crucial, not only to identify the biodiversity of an area, but also to establish the basic, fundamental information to approach ecological and chorological studies, and most importantly to accurately evaluate the threat situation of the species and to design conservation strategies backed with the necessary knowledge.

During this period of intense research activity, I also carried out an important teaching activity in the same university and in different courses and masters, a task I always found particularly attractive because of its direct influence in the education of new generations of researchers, teachers and the people in charge of the management and conservation of our natural heritage. And of all those people interested in discovering and understanding the world around them as well. This might be an overly repeated sentence, but knowledge is vital in order to raise awareness of the environmental problems we’re experiencing.

The second stage of my career is linked to the public company Vaersa, through which I’ve worked in different technical assistances for the Regional Ministry of Environment, throughout the different names it has been called. During this time, my activity has been focused on the management and conservation of rare endemic or threatened flora and natural habitats, attached to the program Flora Microreserves, or in a larger geographical area that comprehends the whole Region of Valencia.

But your specialization is lichenology. What interested you about this field of study?

I believe it was a series of circumstances that influenced my specialization in this group of organisms. I already found them surprising as a student due to their ability to colonize even the most challenging environments, with minimal resources and impossible conditions for any other living being. Later I began collaborating with the lichenology team of the Faculty and I could study them further, their possible applications as bioindicators, the great deal of floristic work still undone or how generally unaware of them the most part of the population is. Ultimately, these organisms offered a wide range of possibilities in research, but also scientific dissemination, all of which has intensely attracted me to this day. Time and circumstances progressively expand the subjects of interest and change the focus of attention, but the specialization plays a very significant role when it comes to inspire your preferences. Furthermore, there’s still so much to learn about these dual organisms that I try to keep up the activity in lichenology, modest and basically floristic, but extremely gratifying for me.

Are you proud to have been involved in any project in particular?

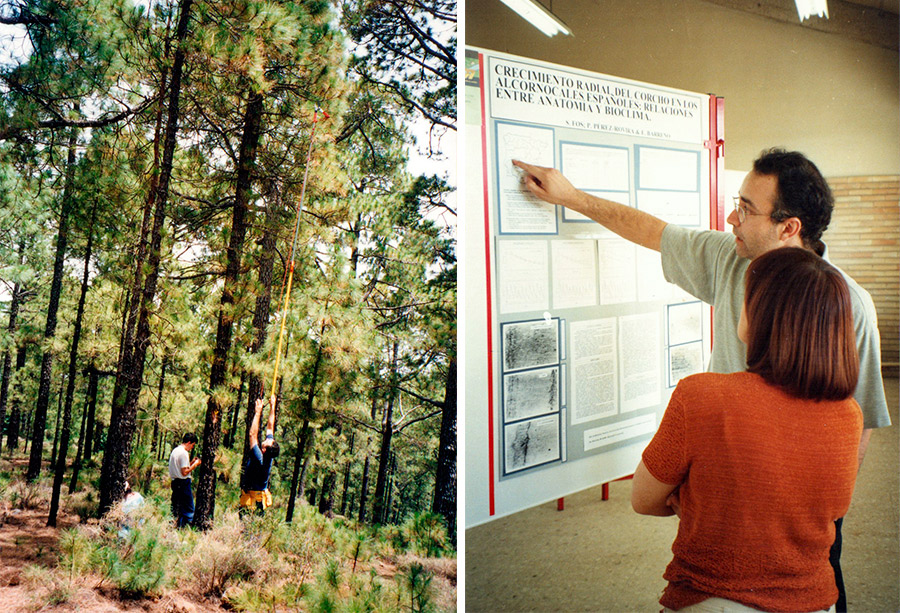

Perhaps my answer might come across as self-centred, but I think the project I feel particularly proud of is the one I conducted in my PhD dissertation. The goal was to prove if lichens, which were already confirmed as excellent bioindicators of heterogenic environmental variables (climate, forests structure and continuity, air quality, substratum characteristics, etc.), could be used as bioindicators of the quality of the cork produced in the main producing areas of the Iberian Peninsula. It was a very interesting project, pioneering from the perspective of lichen bioindication and, moreover, it could have an impact on the quality assessment of this material. The development of this project allowed us to visit and sample other Iberian lands, we had to create a methodology for the extraction of cork cuts to quantify their radial growth with an optical microscope, we also had to climatically analyse all the sampled areas and, eventually, statistically connect all the variables. The results, included in the PhD dissertation and published in the journal Guineana, confirmed a link between the anatomical and densiometric characteristics of cork and the floristic composition of epiphytic lichen communities. It was a long and meticulous work, but, as I said, I feel especially proud of the final results and their impact.

How important are such projects for society at large?

I think the impact on society of such projects is minimal because they cover specialized topics with very specific technical applications. However, that project did have an impact in the cork industry, both for the opportunities that it provided to establish the environmental variables that could be correlated with higher quality productions based on the composition of the epiphytic lichen communities, and for leading studies that lay down the causes of some anomalies in this material that might condition its industrial use. In fact, I have recently held meetings with people of the cork industry to deal with issues concerning this topic.

Back to the present. What does your work consist of?

An important part of my current work is focused on the management and conservation of threatened flora, collecting all the populational information that different teams provide, including the Wildlife Service pertaining to the Regional Ministry, the Centre for Forestry Research and Experimentation (CIEF), the Centre of Conservation of Freshwater Species of the Region of Valencia (CCEDCV) and the flora technicians of all three Valencian provinces, with the contributions of the staff of Nature Parks and environmental agents. Statistical analysis of all the information gathered throughout many years of monitoring allows for the determination of population tendencies, a piece of basic information for decision-making regarding the design, planning and implementation of conservation measures that guarantee the continuity of threatened species. Furthermore, all registers are georeferenced, it has been possible to generate an exhaustive mapping of the populations that minimizes the risk of land transformation projects damaging them.

Another important part of my work is dedicated to drafting the Management Regulations for the Natura 2000 protection areas in our region, doing all the paperwork needed to transform the Sites of Community Importance (SCI), proposed in the first place to ensure the conservation of habitats and species of community importance, into Special Sreas of Conservation (SAC) of biological heritage that originated their declaration. It’s a multidisciplinary work that integrates geographical, economic, cultural and, logically, biological aspects to assess the current situation of the area, the species and the habitats, and this works as a baseline for the establishment of use and management regulations, with concrete measures and actions that improve the current conservation status.

Finally, I’d like to bring up my task in producing, collecting and analysing the floristic richness of the Flora Microreserve Network of the Region of Valencia. It’s truly gratifying being part of this project that’s turning 25 years old. In 1994, the decree for the creation of this original landmark of land protection was issued, though the first microreserves were declared a few years later, in 1998. Being involved in this project and the personal and professional experiences I’ve been able to enjoy alongside Emili Laguna and the rest of the team have been essential in my education as a botanist and as a conservation technician of vascular flora. And also my involvement in the Biodiversity Data Bank of the Region of Valenica (BDBCV), a public platform that compiles all the regional biodiversity and makes it publicly accessible. I consider this project extraordinarily interesting, and I’m actively involved in it out of conviction, whether it’s in the project itself or in the communication, teaching or scientific opportunities it offers.

Do you work alone or in a team?

I have always worked involved in a team. I’ve carried out some individual initiatives, concerning both lichen and vascular flora, or in management and conservation of the network of microreserves, but I’ve developed most of my research and management activity along with colleagues. This way of working is much more fulfilling, and although some conflicts might arise, they haven’t been a big deal, but quite the opposite.

What is the most unpleasant part of your job and the most rewarding?

About the least pleasant part, I’d say the paperwork isn’t very attractive nor gratifying in general. But fortunately, field work outweighs it, especially when I share it with colleagues and friends that allow me to keep making progress in the knowledge of vascular plants. I had specialized in a different group of plants, as I mentioned, so when I joined the team of flora microreserves my attention turned towards vascular plants. Those team trips were absolutely essential for gaining knowledge in this group.

You are not allergic to any plant, are you?

For now, I don’t have any detected allergy.

Imagine you have as much budget as you want. What things would you improve about your work?

With enough budget, rather than changing the work itself, I would change the priorities. As I previously mentioned, I’m especially interested in exploring lichen flora in the Region of Valencia, inventorying it, identifying their needs of conservation and spreading awareness, bringing people closer to all this interesting – but often unseen and far too unknown – biodiversity. That’s why I would focus on these goals.

Do you have any other ongoing project, outside of the strictly professional work?

Besides the projects that make up my professional activity, which I previously mentioned, I’m quite determined in improving —sadly, too slowly and limited to only the species recognisable by sight— the floristic and chorologic information about the lichens in the Region of Valencia. Since my job includes field workdays, I have the chance to visit many areas that have no lichenological information, and I take advantage of these work trips to write down the flora I see. I often collect material samples, either because they seem rare or interesting to me, or because I can easily confirm their identity by revising some of their microscopic or chemical traits. But this task requires an investment of personal time that I can’t always manage to find. Fortunately, I’ve come upon colleagues, Nature Park technicians and environmental agents who cooperate with me in the pursuit of this goal, people who are remarkably committed to understanding our natural heritage and lichens as well. The photos and samples that they keep sending me are extremely valuable in the endeavour of compiling floristic information. I’m truly grateful for all these people that are engaged in this project. Their observations are crucial to find floristic data of many areas that completely lack it, although it is, as I mentioned, basic information. Furthermore, all this information is continuously being added to the Biodiversity Data Bank (BDB), which means it is available to any interested person.

You have published in scientific journals, monographs, etc., but you are also interested in the communication side of science, and you take part in different initiatives

I believe science communication is essential. For this reason, I tried to balance it with scientific publication. My contribution in this matter has to do with the issues I’ve been working on during many years, such as bioindicators, cork oak groves and cork, l’Horta area, the discovery of the Valencian lupin, invasive plants, etc. Honestly, the opportunity to work in scientific dissemination granted by the journal Mètode has been extremely stimulating. And not only that, the rightfully earned recognition of this journal pushes you to be very self-demanding with your work, since it acts as a platform for spreading knowledge and opinions, for raising awareness among the population in different environmental matters.

Another example would be the poster of lichens on hard substrata that you created for the Valencian Government…

Exactly. This series of posters, currently on number 18, helps people approach biodiversity, which is generally unknown for most of them. And lichens fit in that definition. These organisms are, probably, more present anywhere than any other; if we look a bit closer, we’ll always find them around, wherever we are. They are virtually omnipresent, but, at the same time, they are some of the most ignored beings, almost unnoticed. Those posters, very visually attractive, are highly effective at bringing attention and educating our sight.

Or the recent publication of the book Les plantes del nostre entorn. Flora silvestre de Paiporta (‘The plants around us. The wild flora of Paiporta’), and other cities as well

Indeed, these projects, developed together with M. Ángeles Codoñer, are clearly dissemination oriented. The main purpose is to reveal to the locals the botanical heritage that inhabits the everyday landscapes they see. Of course, without sleeping on the scientific —botanical— aspect, but prioritizing traditional uses, popular culture attached to these plants, fun facts, etc. In other words, the issues that might ignite people’s curiosity work as a first step in inspiring the knowledge and fondness towards these plants. In the case of Paiporta, they are linked to artificial environments, crop fields and urban settings, and, for this reason, they are often disregarded or even belittled, but they treasure an extraordinary cultural heritage for its extension and diversity, a heritage worth knowing. And we are sure it will surprise most of the people who are not as connected to the rural and agrarian world. Besides, we show and talk about plants that anyone can find at their doorstep, as it were, and just walking around Paiporta or its surroundings, or any other municipality in the region of l’Horta, or even further.

What is your relationship with the Jardí Botànic of the University of Valencia?

In the Botànic I have many good friends, but the relationship with it hasn’t been very deep. For years, I took part in the trips organized by the Jardí to discover our country and I deposit the Herbarium the material I identify. Speaking of the Herbarium, I actually ask quite a few questions and request some information from Jesús Riera, so I can fix mistakes and complete information in the mentions of the BDB. I could also include in this relationship the editing of the book Catàleg Valencià d’Espècies de Flora Amenaçades (‘Valencian Catalogue of Threatened Flora Species’), edited alongside Antoni Aguilella and Emili Laguna.

You mentioned earlier that you also worked as a teacher. What do you think is important in that area?

Teaching, backed by science dissemination, are the keystones for igniting and fuelling vocations, for educating professionals dedicated to their work and compromised with the social, cultural and political issues involved. Knowing facts is essential, but I deem more important the opportunities that both teaching and science dissemination provide for awakening the interest in the subject matters at hand, for finding crossed implications, which in biology, ecology and botany are many and diverse, for bringing up and defending a critical stance, etc. The professional world needs people who are passionate about their work, and the “rich soil” in which this motivation will grow should be watered in class.

Do you consider yourself a disciple of any particular botanist?

Of course, we can’t advance knowledge without the education and the support of those who come before us in our fields. Regarding lichens, the main responsible figures in my education were Eva Barreno and Violeta Atienza, and as for phanerogams, it was Emili Laguna. Though learning in such fields is a never-ending task and you feed off all the people that share your interests and goals. Throughout all those years, professional and personal experiences have been and still are deeply rewarding in every way.

Which botanist would you have liked to meet personally?

Undoubtedly, Simón de Rojas Clemente, the first Spanish lichenologist, and also my namesake. For me, it would be a dream come true to have the opportunity to study his herbarium sheets again, but I’m afraid it won’t be possible, based on the information I have from previous attempts.

Which era of Botany would you have liked to live in and why?

I think the golden age of Spanish Botany, with great campaigns of prospection and identification of plant biodiversity. Given nowadays the task of inventorying the botanic diversity has not been completed yet, imagine those days. Everything was still to be done, the means were limited, but they weren’t haunted by the rush, the need to publish in high-impact journals, the CV. On the contrary, the hope and the eagerness for knowledge helped overcome many obstacles.

How would you encourage current biology students to pursue the same career as you?

Botany has not drawn much interest from biology students. Generally, this specialization has never been very popular, but botany allows for the discovery and understanding of the world around us and, in addition, there’s still so much to do, even in basic science, and it is very rewarding on a personal level (which I believe is the most important and stimulating one) and on a professional level when you get to the results. This is a time in which naturalist vocations, those that encompass in-field studies and biodiversity in a classic sense, are dangerously fading away, even though they are, to my understanding, the fundamental element that all the knowledge builds upon.