Botanist of the month: Silvia López

She wanted to be a private detective as a child, but with time she considered applying her observation skills to the world of plants. Then, botany became both her profession and passion, given her meticulous nature and liking for fieldwork trips. Silvia López, a doctor in Biology who currently works in environmental consulting, specialised in monitoring endangered flora, is our Botanist of the month.

What attracted you to Botany?

It was a late attraction. From my biggest childhood vocation, becoming a private detective, to landing onto Botany, I went through different phases that eventually led me to study Biology, mainly because of animal ethology. It was during the second year of my degree that I discovered Botany and decided to continue with this specialisation: the behaviour and organisation of plants ended up interesting me more than animal behaviour. Later, as I got to my fifth year, floristics became the star of the show within Botany. The module taught by Gonzalo Mateo required the cataloguing of flora from a territory chosen by us, which in our case was Oropesa del Mar (Castellón). The project, carried out by me along two fellow students, Maria José and Aurora -the first acknowledgment of Crucianella latifolia in the La Plana Alta region- was one of the projects that I have enjoyed the most and brings one of the best memories to me.It was a late attraction. From my biggest childhood vocation, becoming a private detective, to landing onto Botany, I went through different phases that eventually led me to study Biology, mainly because of animal ethology. It was during the second year of my degree that I discovered Botany and decided to continue with this specialisation: the behaviour and organisation of plants ended up interesting me more than animal behaviour. Later, as I got to my fifth year, floristics became the star of the show within Botany. The module taught by Gonzalo Mateo required the cataloguing of flora from a territory chosen by us, which in our case was Oropesa del Mar (Castellón). The project, carried out by me along two fellow students, Maria José and Aurora -the first acknowledgment of Crucianella latifolia in the La Plana Alta region- was one of the projects that I have enjoyed the most and brings one of the best memories to me.

What has your professional career been like so far?

As soon as I finished the degree in 1989, I joined Gonzalo Mateo’s research group at the Department of Botany, at the Burjassot Campus. I started by collaborating in tasks for the VAB Herbarium and developing my degree thesis, titled “Botanical contributions by Dr. Pis Font I Quer to flora in Alicante, Castellón, Valencia and Teruel”. This start let me expand my scarce botanical knowledge and direct my preferences towards taxonomy and chorology. In 1990 I received a two-year research scholarship by the IET (Institute of Studies in Teruel), a scholarship that cemented my path in botany and propelled me to carry out my PhD. In 2000 I had a viva on my thesis, titled “Chorological study of flora in the province of Teruel”.

With the scholarship being over, I saw myself having to balance work with working on my PhD thesis. It was in 1992 that I began collaborating with Carlos Fabregat, setting out on our professional career together. I started working on projects on plant cartography for the Government of Aragón under Carlos’ supervision and participating in the area 4 team for the Habitats project, coordinated by Gonzalo Mateo. In 1995 I started working on my first projects on endangered flora conservation, funded by the Generalitat Valenciana, where I was carrying out prospection, census and distribution studies about the Sideritis javalambrensis, Erodium celtibericum and Goodyera repens species in the Valencian Community. That same year we were allotted the project proposal “Localisation study of unique flora settlements in Teruel (Aragón)”, a project through which I explored the best places in the province and which boosted my PhD thesis. In 1997, with support by the Government of Aragón, I took part in the LIFE project “Conservation of thirteen endangered plant species in Aragón”. Among these plants we find the Sideritis javalambrensis and Puccinellia pungens. Since then, my professional path has mostly continued in that direction, revolving around the conservation of endangered flora species and habitat cartography in the southern Iberian System.

From both a professional and personal point of view, the province of Teruel has become greatly important to me, particularly three of its symbolic environments: mountain ranges Sierra de Javalambre, with a high diversity of endemic floral species, and Sierra de Gúdar, nicknamed the “Teruel’s little Pyrenees” since its species mostly share a Cantabro-Pyrenean distribution; and the lake Laguna de Gallocanta. As regards the latter, I am very proud of being a member of its Scientific Advisory Board since June, 2009.

The best part about this project is that I can perfectly combine it with my research in taxonomy and chorology, allowing me to keep on collaborating with Gonzalo Mateo’s research group on the study of phanerogams as well. This flexibility let me continue with my management tasks at the VAB Herbarium -with two collaboration scholarships, in 1997 and 1998-, until it was moved to the Botànic, when several herbariums from the University of Valencia were unified as the VAL Herbarium. I was also able to further pursue research in taxonomy. Studying taxonomies whose characteristics do not fit the previously established boxes as defined by other botanists unleashes my inner detective, and it is precisely this sort of “wake-up call” when an observed plant displays differences previously unregistered what led me to study and propose the description of new species like the Erodium aguilellae or Gentianella hispanica. It is also very rewarding, being able to prove that species that were until then considered synonymic to others are actually new species, as it is the case of the Santolina ageratifolia, which was identified by Ignacio Jordan de Asso as a new species in 1784 and synonymised with S. rosmarinifolia and then abandoned until 1997, when we re-claimed it. Today this species is considered to be endemic to a restricted area in the western end of Teruel, and census, distribution and state of conservation studies have been carried out on it by the Government of Aragón, the results of which led us to label the species as vulnerable in the Red List of Spanish Vascular Flora. And discovering new rare plant locations, expanding their known area of distribution, is also incredibly exciting in the field of chorology; I still remember my first eureka moment with Carlos when we found Goodyera repens in the Maestrat (eastern Iberian System).

What is your current job about?

Carlos Fabregat and I are in charge of natural environment management, more specifically vegetation and flora. We endow public administration -both central and local- with the necessary resources for the management of the territory, carrying out prospection, localisation and monitoring tasks, state of conservation analyses and management proposals with endangered flora species, plant cartography, studies on floristic chorology and management, etc. And, but to a limited extent, we also work with private companies for floristic or habitat cartography studies, we collaborate with architects for the design of spatial plans and we work on botany outreach via courses, trips, etc.

Fieldwork trips are essential for the carrying out of our tasks, which have allowed us to acquire solid knowledge on the flora and vegetation from the territory we work on, mainly the Valencian Community and Aragón. We are like bears in a way: as spring comes, we leave our cave for the mountains and later we hibernate in our offices, writing the reports that we will have to submit by the end of the year.

Your specialty is endangered flora conservation, what interested you in this field of study?

Conservation studies allow you to delve deeply into a species: to preserve them, you need to obtain very thorough information, encompassing many fields of knowledge that are interconnected. Such fields include, among others, taxonomy, chorology, demography, reproductive biology, ecology, genetics and sociology. The assessment of the state of conservation of a taxon is made by considering every parameter and analysing the presence of pressures both natural and anthropogenic, or the presence of threats that may act in the short or long term. Depending on results, we must then suggest management guidelines accordingly, to counteract the possible pressures and threats and guarantee the survivance of these populations or species. The more extensive and accurate the information, the more effective the management; however, public administrations count on limited resources, and therefore it is important to balance efficiency and minimal expenses out as much as possible. Sometimes it is also the case that previous exhaustive studies are not possible because of time limitations, and then we resort to emergency actions, choosing the most effective course of action based on the available information at the moment.

Another relevant aspect about conservation is that this is not an activity that is alien to society, since understanding and acceptance on the part of the inhabitants of the municipalities involved, of the stockbreeders and farmers in the area, contributes to higher success chances for plant recovery. On the other hand, the involvement of citizens via voluntary work translates into the creation of a social force with the power of demanding political parties the inclusion and compliance of serious and effective measures for the protection of the natural environment in their electoral programmes.

Are you proud about having participated in any particular project?

I feel very honoured to have participated in the description of the Bunium and Conopodium genera -along with Gonzalo Mateo- for the 10th volume of Flora Iberica. For someone like me, with a special attraction towards taxonomy, this was a highly enriching experience both professionally and intellectually, besides the great pride in appearing as an author in one of the most important botany works in the Iberian Peninsula.

There are two other projects that I find to be personally rewarding: one of them being the Atlas de Flora Amenazada (Atlas of Endangered Flora), with its subsequent appendixes. At the beginning of this project, I was part and responsible of the group of the University of Valencia along Jaime Güemes and Josep Antoni Roselló. The result was the publication of the first Atlas y Libro Rojo de la Flora Vascular Amenazada de España (Atlas and Red List of Endangered Vascular Flora in Spain) in 2003. This publication represented my professional maturity in the field of Plant Conservation, and thanks to the study of demographical variability of the Oxytropis jabalambrensis, included in this project and which I carried out with Carlos Fabregat, I was able to delve more into the species on which we are working since 1999 for the Government of Aragón.

And last but not least, I want to mention the project “Atlas de la Flora de Aragón” (Atlas of Flora in Aragón), started in 2002 and as a result of which a webpage that compiles all knowledge on vascular flora taxonomy and distribution in Aragón was created. This project, coordinated and led by Daniel Gómez, resulted from a collaboration agreement between the Department of Environment of the Government of Aragón and the Pyrenean Institute of Ecology, counting with the participation of over 20 people. Such a project, of which I am very proud, included all the data from my PhD thesis.

Tell us about your current projects

We just finished a LIFE+ project called “Monitoring network for plant species and habitats of Community interest in Aragón (RESECOM)”, carried out by the Department of Rural Development and Sustainability of the Government of Aragón and the Pyrenean Institute of Ecology (IPE-CSIC). The goal was to implement a monitoring network for species and natural habitats of community interest in nature protection areas Natura 2000 in Aragón so as to obtain first-hand data for the improvement of the managements of the species and habitats that are the object of the project. The originality of the enterprise lies in the involvement of not only experts and Nature Protection Service Officers for the organisation of the physical monitoring network, but also ordinary citizens, volunteers who love plants and their conservation.

What is your relationship with the Jardí Botànic of the University of Valencia?

Our relationship traces back to the 90’s, as I was developing my PhD thesis and used to spend some mornings taking notes at the herbarium, before the herbariums of the Faculty of Pharmacy (VF Herbarium) and the Faculty of Biological Sciences (VAB Herbarium) were merged together. It was also around this period, my scholarship being over and having gone to sign on the dole, that I started a course to become an environmental educator and decided to do my practicum at the Botànic, where I led guided tours under María José Carrau’s supervision. Later on, as the research building was built and my thesis tutor, Gonzalo Mateo, moved to the Jardí Botànic, I moved with him as a member of his group, where I stayed as a researcher until 2017. I worked in several projects during this period, some related to the herbarium such as “Restauration, categorisation and computerisation of VAL Herbarium collections within the GBIF network”, others related to the conservation of flora, like “Study of endangered local plants to Penyagolosa (Valencia) and “Study of endangered local plants to Tinença de Benifassà (Castellón). I have also participated in congresses and carried out botanical research and publications on their occasion. I was also granted a research scholarship in 2013 which I had requested at the 30th Research Scholarship Contest of the IET (Institute of Studies in Teruel) for the carrying out of the project “Taxonomical study of the Sideritis javalambrensis (Magnoliopsida, Labiatae), exclusive natural patrimony to Teruel”, and which was sponsored by Isabel Mateu, director of the Botànicat the time. I have taught some courses on flora and conservation at the Botànic as well. I currently still participate in different courses and take part in the collection of seeds for the Germplasm Bank along with Elena Estrelles.

Does your work allow you to learn about non-botanical subjects?

I guess you could say so. Research projects demand abilities seemingly unrelated to the main researched activity, which allows you to learn about a series of transversal subjects. I cannot think of an example right now, but I can say that on a personal level botany has taught me to be more observant, meticulous and analytical, and most importantly, to learn how to respect and wonder at nature.

How important do you think scientific outreach is?

Outreach is a must to get society, more specifically rural and urban citizens, to get involved in the conservation of nature. Knowledge favours an understanding of the natural environment and our role in it. A society that understands how nature operates will better grasp the risks of not striving for its conservation and urge politicians to apply conservation policies.

How do you assess the employment situation in the sector?

The employment situation is quite precarious, especially if you work as a freelancer. Things are getting more and more difficult in terms of bureaucracy, participating in funding contests, low budgets, and you always feel insecure about your chances of continuity. Overall, I feel like if economic development and growth prevail over the conservation of the natural environment -and if on general terms society as a whole sees it the same and supports this view-, then governments will not limit developmentalism in the territory and, therefore, us botanists will be dispensable in a relatively near future.

What does the future hold for botany?

The botany of the future? I imagine it as a complex algorithm applied to plant images taken by a satellite, and the “botanist” would be a robot that produces conclusions from them. Us humans will be outdated.

Whose disciple do you consider yourself to be?

I consider myself to be a disciple of Gonzalo Mateo, with whom I truly got to know about botany and botanists who made history. I learned about terminology, taxonomy and chorology, how to manage a herbarium, search and gather bibliographical information, do fieldwork and, above all, I discovered a territory that has ended up being very symbolic for me, the province of Teruel. And in Gonzalo Mateo’s group I met one of the best and most meticulous botanists, Carlos Fabregat, with whom I set out on one of the most exciting trips there is, life.

What era of Botany would you have liked to live in and why?

I have always dreamed of time travelling not to the future, but to the past, so that I could explore the earth prior to humanity started to change the landscape so drastically, a travel back to the end of the Pleistocene. However, I think the closest to that fantasy would be getting to experience the era of the great botanical expeditions in the 18th Century and being able to take part in them which, as a woman, would have been quite hard.

In all these years as a botanist, what is the most curious situation you have come across?

Our job requires a lot of fieldwork, so Carlos and I have frequently taken our children Jorge and Sergio with us, ever since they were babies. And because of that insatiable curiosity of children, they would always ask us about everything and wonder at their surroundings -plants, insects, stones, villages…- and, without we even realising it, they were learning about what we would discuss, Carlos and I.

One time, during a vegetation mapping session in Javalambre (Aragón), we were walking through a forest path with a wonderful ripe Spanish juniper when, after turning at a corner, we were surprised by a Scots Pine repopulation. Confused and annoyed by the presence of this human alteration that had broken the harmony of the landscape, we said out loud: “What is with these pine trees?” To which Jorge, 4 years old at the time, answered in a condescending tone: “Pinus sylvestris”, as if he were thinking, “what a shame, my parents do not seem to know what they are doing anymore”.

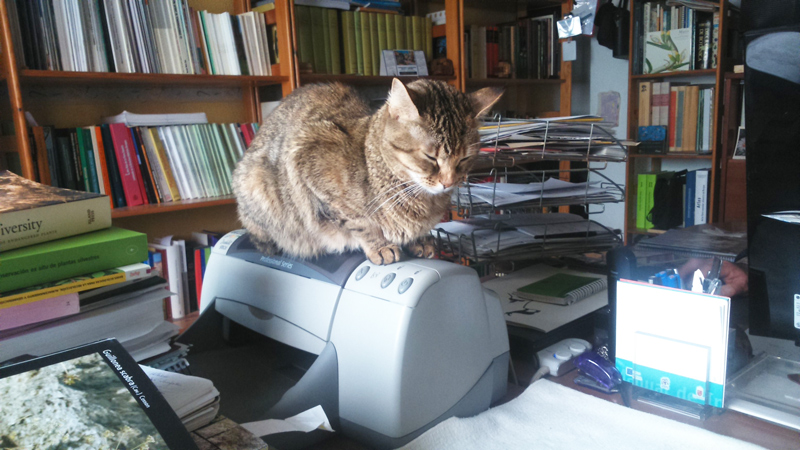

In the case of a fire, what would you save from your office?

I would save our cat Tesla. Our office is right next to where we live and every morning, as we leave for work, Tesla joins us and makes us company by sleeping on top of documents, helping Carlos with cartography or insistently walking over our keyboards.