Botanist of the month- Sara Mira

Sara Mira came to botany through plant cell biology, not specially attracted by the beauty of plants, but by the spectacle of plant cells under the microscope. This researcher and professor of the Universidad Politénica de Madrid is our botanist of the month in Espores, the journal of the Jardí Botànic of the Universitat de València.

What was the thing that attracted you to botany?

The curiosity about knowing more about a subject that was usually neglected at different educational levels. I always liked the subject of biology, but it was very focused on the animal kingdom, and this lack aroused my interest in learning about plant biology. Later, when I was studying the degree in Biology, I was so lucky to have a plant histology professor, Ana Ibars, who transmitted a lot of enthusiasm. Contrary to many other researchers, I approached botany through plant cell biology, which I think makes perfect sense: if plants are beautiful, plant cells under the microscope are such a spectacle.

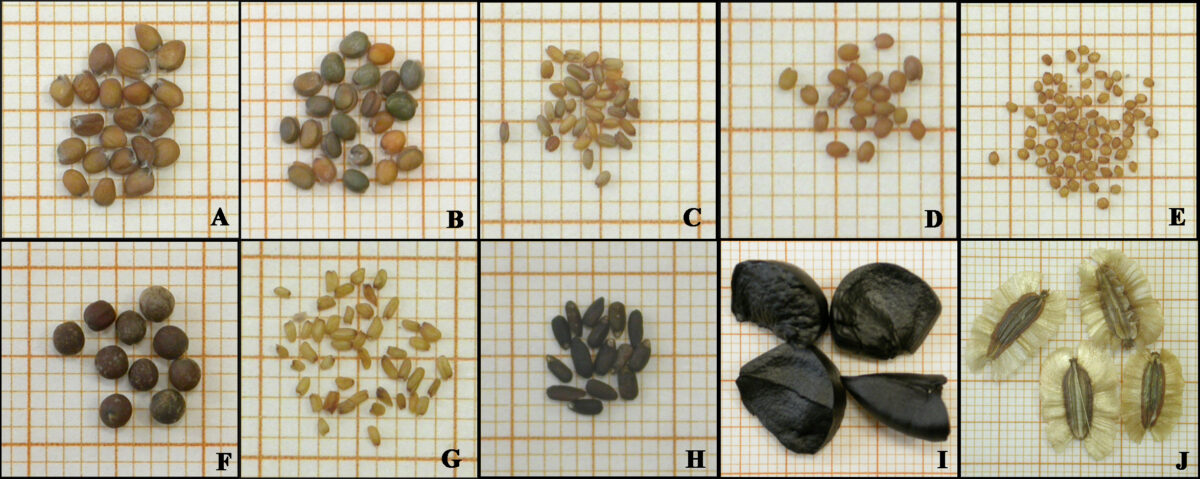

Seeds of the endangered endemic Silene diclinis and their heterogeneity of colours. Picture: Sara Mira.

How would you summarize your professional career?

I graduated in Biology at the Universitat de València and I did my PhD thesis on seed conservation between the Agronomist Higher Technical School of Engineering (ETSI, Spanish acronym) of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and the Jardí Botànic of the Universitat de València. I have worked in two European projects on seed conservation and germplasm banks, Genmedoc and Ensconet, as well as in the seed bank of the botanical garden of Olarizu (Vitoria, Spain). I have also collaborated with different international research centres. I am currently professor of the Higher Technical School of Agronomy, Food and Biosystems Engineering (formerly E.T.S.I) at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

What does your work involve?

My scientific interest lies in seed biology, more specifically in understanding the processes of seed germination and seed ageing. My career integrates basic science applied in both conservation biology and agronomy, and it is focused on a deep understanding of seed ageing mechanisms with the aim of optimising conservation protocols to improve seed propagation. I work with wild species and species of agronomic or forestry interest, developing protocols for germination, conservation and monitoring of the quality of stored seeds with the aim of optimising plant production protocols.

What was it about your specialisation in seed biology that interested you?

The idea that a cell structure is able to survive even under extreme conditions for long periods of time is fascinating. Understanding in depth what biological processes enable such longevity is an ongoing challenge.

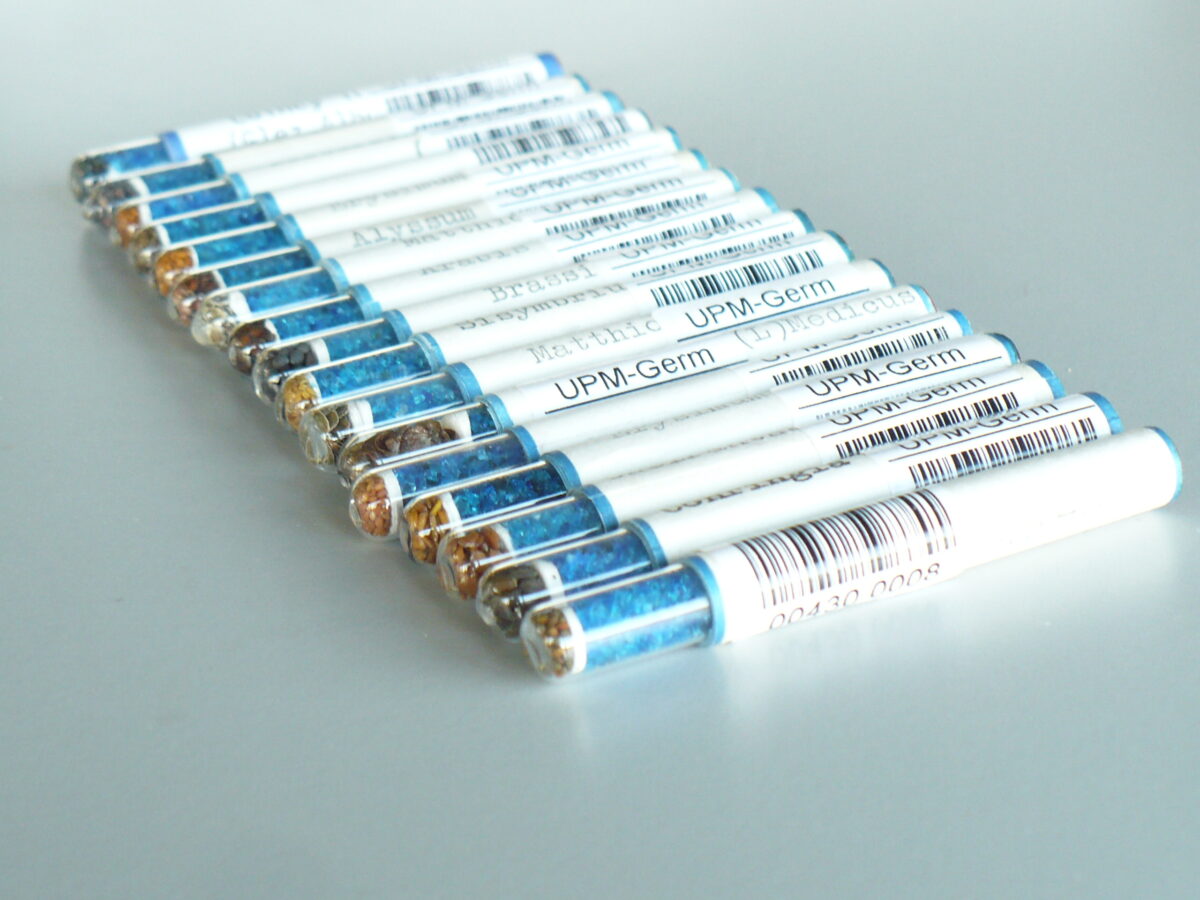

Collection of Ulmus glabra seeds in Puerto de la Morcuera (Madrid) in 2014. Picture: Sara Mira.

Do you feel especially proud of any of the projects you have participated in?

I have worked on two European projects on seed conservation and germplasm banks, as a predoctoral researcher at Genmedoc and as a postdoctoral researcher at Ensconet. They allowed me to have an overview on the state of plant genetic resources conservation in Europe, get to know different institutions, compare protocols and create international work networks. I think this type of international networks are essential to connect institutions focused on plant conservation.

Pancratium maritimum seeds used in ageing trials. Picture: Sara Mira.

How do you think your work has changed over the years?

There has been an obvious and rapid technological change, with new techniques and processes constantly appearing. Moreover, current research necessarily involves teamwork, multidisciplinary and internalisation. Nowadays, both the funding of projects where different groups work in coordination and the increased ease of communication encourage collaboration in different fields and the ability to tackle problems from different approaches.

What are the most unpleasant and the most rewarding aspects of your job?

Working in scientific research means that many projects and experiments does not turn out as expected, mistakes are commonplace and we have to get used to frustration. At the same time, however, it is a job without any routine which poses continuous challenges and this is most rewarding.

What type of relationship do you have with the Jardí Botànic of the Universitat de València?

As an undergraduate student, I collaborated in the plant histology laboratory with Ana Ibars for several years. Then I worked with Elena Estrelles in the seed bank, where I did part of my PhD thesis. I share a lot of affinity and interests with this institution and I hope to continue collaborating with them for many years to come.

Fruit and seed collection of the endemic Silene diclinis for studies on their germination and ex situ conservation in seed banks. Picture: Sara Mira.

What would you highlight about the field of teaching?

I believe it is important to train professionals not only with applied and basic broad knowledge, which allows them to adapt to a constantly changing world; but also, with a critical scientific view so that they are able to draw their own conclusions and solutions to the problems they face. This must also go hand in hand with a commitment to improving our society and environment.

Silene diclinis seeds collected in Pla de Mora in 2002 for germination and conservation studies. Picture: Sara Mira.

What role does dissemination of knowledge play for you?

Scientific dissemination is growing in Spain. There are more and more agencies focused on scientific issues. Being able to spread the knowledge of research centres plays an essential role in an increasingly complex world. In the coming years I would love to see this interest in science grow, so that it becomes more common to find scientific information in the press and on social networks.

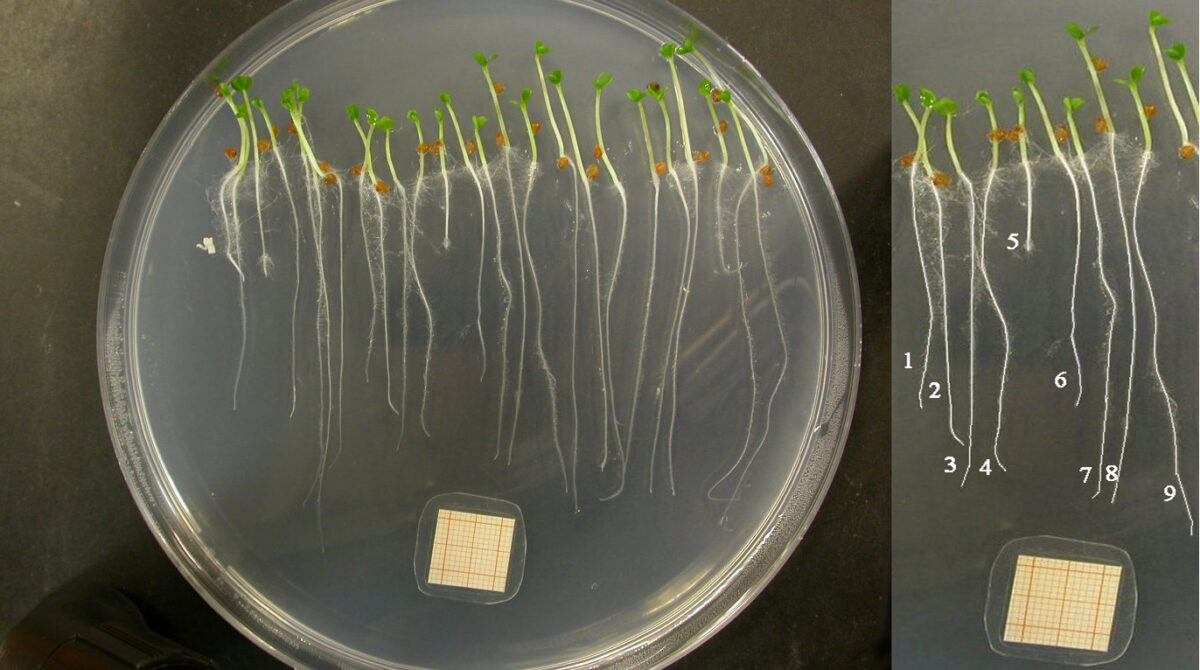

Seed germination of Eruca vesicaria, processed by image analysis to measure radicle length and germination speed. Picture: Sara Mira.

How would you encourage current biology students to pursue the same career as you?

I think that there are two essential qualities for a student today: perseverance and flexibility. One of the positive aspects of current biology studies is the proliferation of degrees, there are many academic paths to follow for getting training that allows you to develop professionally.

What tools do you usually need?

There are some parts of my work on seed germination and longevity that, despite requiring complex technical knowledge, can be develop with simple and affordable materials. For instance, I am interested in seed biology, which involves germination studies on problematic species aimed at optimising their propagation protocols. The results have a practical application, they allow the plant breeders we collaborate with to characterise seed lots and improve the species’ propagation protocols. To carry out these studies on seed germination, all that is needed is a material in which to germinate seeds (soil, filter paper, etc.) and a chamber that can maintain adequate light and temperature conditions. It is a basic infrastructure that makes it possible to broaden our knowledge of plant species.

Is there any essential skill for your job?

I believe that perseverance and problem-solving skills are both essential qualities for daily research activities. For example, fine-tuning a laboratory technique can be a very frustrating process as you may go home day after day with no results due to the new problems you have to tackle.

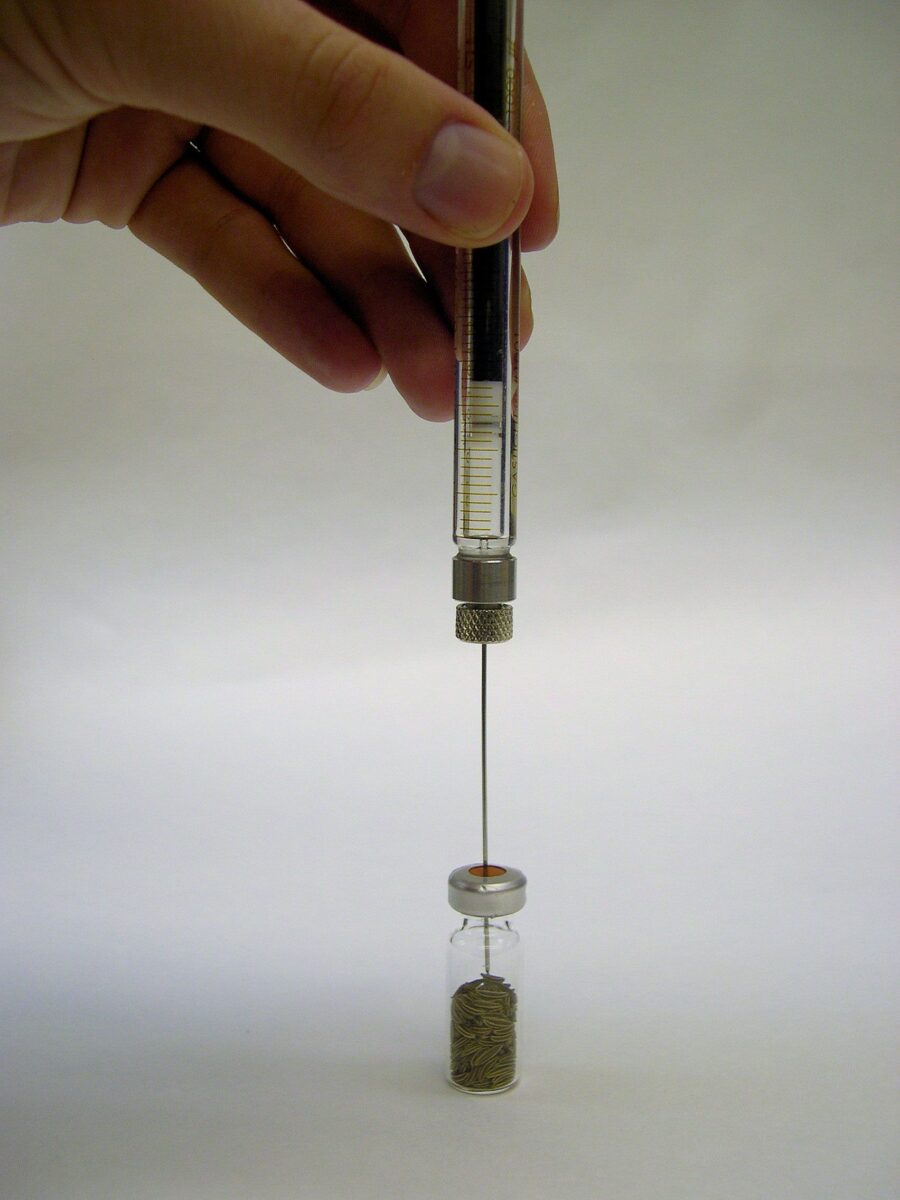

DNA extraction from stored Secale cereale seeds to analyse their genetic and epigenetic stability during ageing. Picture: Sara Mira.

Which botanist would you have liked to meet?

She is not strictly a botanist, but I would have liked to meet Lynn Margulis, a scientist who made great conceptual advances in biology and was practically unheard in biology classrooms until recently. Although her name has been made in recent years through several conferences about her, her contribution was that great that there is still much to be heard.

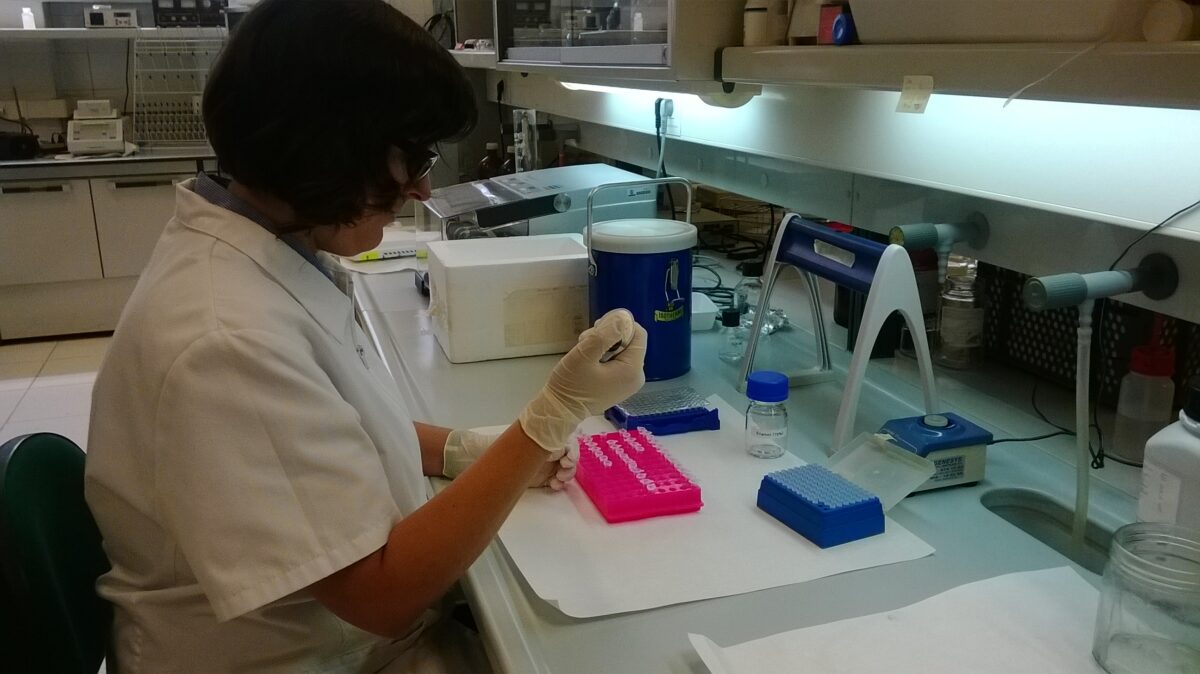

Sulphuric acid scarification of forest seeds during the Workshop on current technologies of forest seed treatment held in 2012 at the Kostrzyca Forest Gene Bank in Poland