Botanist of the month: M. Ángeles Alonso

PhD in Biology and professor of Botany in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resources at the University of Alicante, member of its Botany and Plant Conservation research group, coordinator of the Biology Degree and director of the Villena branch of the same University. M. Ángeles Alonso firmly believes that you can only conserve if you know about it, which is why teaching and disseminating the world of plants is her passion. She is a specialist in salt marshes or, as she would say, a “really salty” (meaning “really friendly”) botanist.

What attracted you to Botany?

My childhood was spent in a village in the province of Castellón called Algimia de Almonacid, and there I grew up in the middle of nature, so I had my inclination towards biology from a very early age, although if it had been for my father I would have devoted myself to ornithology. The love of plants certainly came to me via “chloroplastic”, a maternal inheritance, from the female line of my family. And it all materialised in the first year of Biology, when we went to do some field work in the Mountain range of Salinas (Villena) and I discovered how wonderful it was to recognise plants and know their names. From then on, it was very clear to me that I wanted to dedicate myself to the study of plants.

Tell us a bit about your profesional career

As I told you before, my life as a “botanist” began in a field campaign in the first summer of university. Our class was the first one and the teaching staff was arriving as we moved up to the next year. In the second year, we had Botany as a subject and a very young botanist from the University of Valencia, Manuel B. Crespo, came to teach it with a lot of enthusiasm, ideas and projects. It was in that first year that the embryo of what would later become the ABH herbarium of the University of Alicante, which will be 30 years old next year, was born. That same year, 1990, I, as a biology student, did not hesitate to go and talk to him to help him in this incipient group of botanists that was being created; a collaboration that has lasted until now and that I hope will last much more. The following year another botanist arrived, in this case from the University of Murcia, Antonio de la Torre, and little by little the Alicante group began to take shape. They have been the two botanists who facilitated my professional career as a botanist.

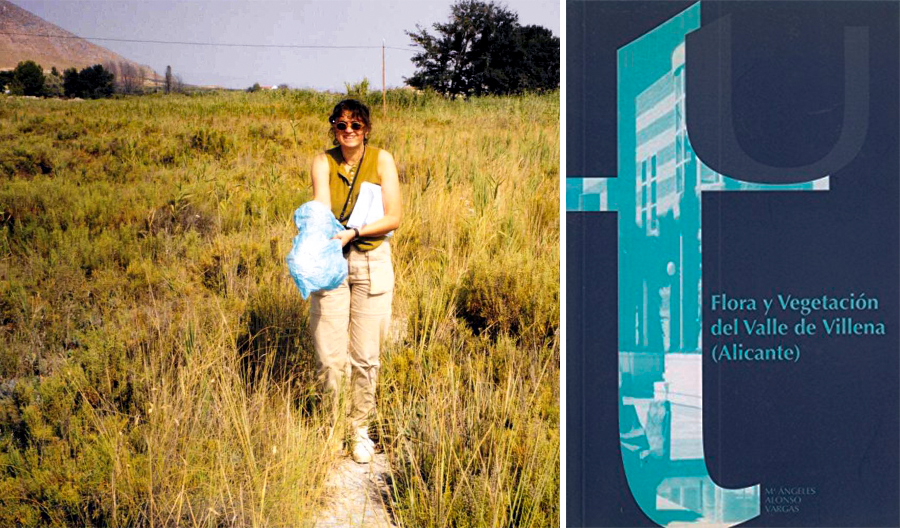

My first research work was my dissertation, on the flora and vegetation of the Villena Valley, which conditioned my main line of research on which I have worked throughout my career and on which I continue to work: the plants of the salt marshes, in all their versions, flora, vegetation, conservation, taxonomy, etc. The Villena Valley, one of the most arid and continental valleys in the Valencian Community, has gypsum outcrops and salt water wells which, together with the climate, conditioned the appearance of very saline areas. I became so fascinated by these plants that my doctoral thesis was focused on the salt marshes of the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula… You could say that I am a “really salty” (meaning “really friendly”) botanist.

But although my main line of research is halophilic plants, I have worked in many branches of botany; this always happens, the projects condition, to a certain extent, the topics you have to work on. As a group we have worked on environmental impact study projects, in collaboration with administrations, in conservation biology, in taxonomic work for floras (Flora Valentina, Flora Iberica), etc., and in the direction of doctoral theses which, on occasions, have not been focused on my main line of research.

For example, I have directed some doctoral theses in South American territories (Peru, Colombia and Venezuela) and, although they were not strictly speaking about salt marshes, all three were related to aquatic ecosystems. Field experiences and flora from other places enriched me as a person and as a botanist. Other doctoral theses I have directed were in my line of research, such as two on the genus Sarcocornia and the genus Tamarix and another on the functional diversity of salt marshes, more focused on the ecology of the ecosystem. I have also had fellows who have worked on other topics such as invasive plants or non-halophilic genera such as Biscutella.

In the last four years, thanks to a European project, we have been able to work in South Africa, focusing on bulbous plants of the Hyancinthaceae family, a group of which we have with us the leading expert in the family, Mario Martínez-Azorín, another member of the Botany and Plant Conservation research group at the University of Alicante, to which I belong.

Which is the basic skill for your work?

Observation and patience are essential to work in Botany, as I conceive it, because as in everything else, first of all we should define what a botanist is, since times are changing and so are conceptions. For me, a botanist is someone who studies and works with plants, from the actual field trips, who recognises plants when they are fresh and when they are dry, who works with them from the moment they are collected to, if necessary, working with them in the laboratory to carry out molecular biology work. Observation and patience are therefore essential. Memory could also be included, but in this case memory and learning are closely related to emotions, so the important thing is that whatever you do, you do it from the point of view of emotion.

What does your professional day-to-day life consist of?

Unfortunately, my day-to-day life at the University is far from what I would like to do as a botanist, although every day I look for that moment of encounter with plants. I am currently taking on two management positions, which take up a high percentage of my time, but it is only transitional; I will return to devote one hundred percent of my time to teaching and studying plants. Even so, every year I make one, two or three trips to the field, whether it is a collection campaign or a stay in a herbarium or research centre.

Are you proud to have been involved in a particular project or discovery?

I was very lucky to finish my degree just when the Habitat project was launched. As I mentioned, I was already collaborating with the Botany group in Alicante and the group was part of the Levante team led by Manuel Costa Talens. We were the Alicante sub-team. It was a very important experience for my training, because we went out to the field a lot, we made many inventories of vegetation in different habitats, a world of plant names, of determination work, etc. Besides, we started in summer and my mentors told me that you have to recognise plants at all times of the year….. When spring came, some of the plants I recognised when they were dry I did not know when they were in flower. It was a lot of work, but lucky for my apprenticeship.

Later, as a senior botanist, I am very proud to participate in the Flora iberica project, a work with which I have learned a lot throughout my professional life and in which I have had the good fortune to participate in its latest published volumes.

As for my special discovery, I would like to mention the first plant described by me, discovered during one of my research stays in Argentina. It is a halophilic plant from the salt marshes of Añelo (Neuquén) and we named it Suaeda neuquenensis.

How important are such projects for society at large?

In recent times, the university has been attaching great importance to the transfer of knowledge to society, both to the business world and to the social and political fabric. The Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 was a milestone for the environment in this sense. Attempts were made to establish conservation and sustainable development policies, but it was realised that, although there was a lot of scientific information on plants, animals and habitats, there were no systematised documents that administrations could use and, if necessary, establish such policies. That is why the CORINE (Coordination of Information on the Environment) project, from which the Habitat project I was referring to is derived, proposed the creation of these inventories. This project has had a great impact on the conservation of ecosystems. This project, together with the Catalogue of Rare and Endangered Endemic Flora, in which the Botany research group of the University of Alicante has also participated, are possibly the best conservation management tools we have been able to pass on to public administrations.

What are you working on now in the research group?

We are currently working on the publication of the results of several projects that have taken place over the last few years. A European project, which we have developed in South Africa, and from which we have very good results with the publication of several new species. The Flora iberica project, in which we are working intensively on Gramineae. Soon, these last volumes will see the light of day and, with them, this magnificent work will come to an end. There are also some articles yet to be published from recent doctoral theses that have been read in the Research Group. However, I can highlight one work this year, which has been incredibly popular in the media, and that is the description of a new species of carnivorous plant, Pinguicula saetabensis, in the mountains of Setabria (Valencia). This discovery has been reported by several television stations and we have made some reports that have been broadcasted on their channels. So I can conclude that I am satisfied to see the results of the different projects and excited about the new doors of research that are opening up for us.

Talking about mass-media… Outreach is also part of your career. Talks, radio programmes… Tell us some of these experiences and why you dedicate part of your time to outreach.

I have always had a great vocation for teaching, and also a certain aptitude for communication, so I like to be able to teach, and what better than to teach what I am passionate about, the world of plants. Over time, I have discovered that these transfer channels are necessary. That is why, in the framework of my activities as a professional, I incorporate it in all areas: I am always ready to go wherever they want to listen to me if the aim is to transmit the importance of plants. To tell you about some of these recent experiences, because I am the Director of the University Campus in Villena, I was asked to take part in a programme that is broadcast on a local radio station in my town called “The music hidden in books”. The scheme of the programme is as follows: a person chooses a book and a discussion takes place, and in the middle of the interview, music related to the book is introduced, or directly songs that are mentioned in the book. I made it difficult for the interviewers, who had to read all the books chosen by the interviewee, because the one chosen was Ramón Morales’ book “Una flora literaria: el mundo vegetal en la obra de Cervantes”. Surprisingly, it was very well received, people wrote to us on the radio to tell us to do a second part, that they learned a lot about plants, that they were unaware of many of the things we told them about plants as well known to us as tomatoes and pumpkins, and that they had never heard of them.

And the last thing I had to face was right here, in the Jardí Botànic of the University of Valencia, as a “plant monologist”. A microphone and to tell the audience how wonderful the world of plants is. A great experience, also surrounded by music.

In short, wherever I have the opportunity to spread the word about Botany I go: schools, secondary schools, programmes organised by the University aimed at the general public such as “La nit de ciència” (“The night of Science”) or for institutes such as “Ven a hacer prácticas a la Universidad” (“Come and do an internship at the University”), university extension courses, etc. I firmly believe in the phrase “you can only conserve if you know about it” and who better than us botanists to make everyone know about plants and give them the value they have?

As a teacher and coordinator of the Biology degree at the University of Alicante, what are you most satisfied with and what would you improve?

I love teaching, it is one of the best parts of my job, when I close the classroom door I leave everything outside and give the best of myself. I am very concerned about reaching the new generations and I realise that each time new students arrive who have nothing to do with the first ones I had, and of course, neither do I. But that is why I am also concerned about my educational renewal as a teacher, because my aim is to get to them and make them like botany as much as I like it. I am already paid when a student comes to me and says: “I did not like Botany at all but now that I have finished it has been one of my favourite subjects”. What would I change? The number of students. I think the university is overcrowded and the teacher-student ratio is not very low. We have around 70 students per class and it is difficult to work individually with everyone. As for the coordination of the Biology Degree… it’s crazy, a lot of bureaucracy, and it’s difficult for everyone to be happy with you. Everything is regulated, fortunately, but in this country it seems that the rules are there to be broken and that is why it is a constant struggle. It is a complicated job, but someone has to do it. It is one of those positions that you think everyone should go through here so that they know what it is all about.

How would you encourage current biology students to pursue the same career as you?

Sometimes I have to receive baccalaureate students in the Faculty of Science, and I have to talk to them about all the degrees, we have seven in the Faculty, and when it is the turn of the Biology degree I tell them: why do biology? because it is the most beautiful degree and the one in which you learn about life in all its extension, what else could you ask for?

What would you point out about your role as director of the Villena University Campus of the University of Alicante?

I have to say that I am a person who first dives into the pool and then looks to see if there is water… In this case I was offered the chance to manage the University Campus in Villena, created for university extension, and it was a challenge as I had never carried out an activity of this nature, but also an opportunity: to work to bring the University to my city. An experience that, today, almost three years later, I can say has been enriching. I learn every day, not only from the management and administration of the Campus itself, but also from the fact that this position has given me the opportunity to meet many people, professors from the University of Alicante itself who work alongside me and who, if it had not been for the activities of the Campus, it is possible that I would not have met them. And, on the other hand, wonderful people from my city who you didn’t even know about their existence and their values. This work opens your eyes to the knowledge of what is being done in your own university and to the needs and concerns, in my case, of the society of Villena, which in many ways can be extrapolated to the general public.

Another of your interests is working for the inclusion of women in the STEM degrees

You may say that we are at a time when we focus a lot on the visibility of women in areas that are mainly male… Well, it is about time! I am a firm fighter for changing mentalities, because this is not a question of equality, but of mentality. I had my revolutionary period of being at the forefront of the fight for equality, but now I am in a quieter period of reflection. It is not about doing the same things a man does, it is about doing things the way a woman would do them. In this sense, society is very much to blame for the fact that women’s presence in science and engineering careers is in the minority. I am sure that many people think things like: “well, now women can choose whatever they want”, “if there are no women it is because they do not want to do them”, but things are not that easy. With little knowledge of how social forces work, invisible beliefs rooted in our unconscious, laws that govern societies, which are difficult to change but fortunately are not immutable, we can understand that it is not just a question of opening the door of a faculty so that it is filled with women. In my opinion, it is unacceptable for a primary school girl to say that she is a girl and that, although she would like to be an engineer, it is not an option she would consider, that it is a boy’s thing. And this is happening. What I have just told you is a real response from a girl in a school this year. In this sense, from the University of Alicante we are taking a programme to all the secondary schools in the province that have wanted to participate, called “Quiero ser ingeniera” (“I want to be an engineer”), which aims to break these taboos and bring to light female references in this type of careers. This idea of role models works, “if she could do it, so can I”, “if she broke the gap, I will change the system”. In addition, we are currently working to include the gender and inclusion perspective in the degree programmes in the Faculty of Science.

What is your relationship with the Jardí Botànic?

For me, the Jardí Botànic is my friends’ home. I have come here many times, either for reasons related to research, with students I have brought on botanical excursions and also to some of the tributes that have been paid to botanists such as Manuel Costa. For me, Manolo has become “my botanical grandfather”. My doctoral thesis has a large part of phytosociology, and while I was doing it he was always willing to help me and teach me, and he was also the leader of the Levantine group of the Habitat project I mentioned earlier. On the other hand, I currently share with Jaime Güemes the participation in the Flora Iberica project.

What is the most unpleasant part of your job and the most rewarding?

I do not know how it will be understood if I tell you that there is no unpleasant part of my work as a botanist, but digging a little… well, I could tell you how little help basic science is getting these days. They are all rewarding, but if there is one thing about my job that I like above all else, it is the collecting trips. I do not care about the conditions in which I have to work, whether it is in the Andes at 4,000 metres above sea level, with a donkey as the only vehicle to carry the presses, or eating a wet sandwich (it is quite disgusting to eat wet bread) because it kept raining in the Colombian moorland, or going out at dawn and ending up collecting some plants using the car headlights because the night is upon us…

What would you save from your workplace in case of fire?

The herbarium is part of our life, there is effort, joys, hardships, in each of those sheets there is a piece of each of the botanists who collected and pressed it, it is our legacy and sometimes it is difficult to understand the value of a herbarium in universities and research centres. We have been “temporarily” in a building with many structural deficiencies for about 20 years, and we have had two major problems with the herbarium and my heart still cringes at the thought of the disaster that could have been the loss of our herbarium. It is irreparable.

What future awaits Botany?

Botany is one of the basic sciences that will never disappear. Depending on the times they are perceived as more or less important in research budgets, but as much as applied sciences now emerge as the most cutting-edge, they would not exist without their foundations. And botany, along with other basic sciences, is the foundation of knowledge. The problem I see is that there are fewer and fewer young people who want to dedicate themselves to it, because the truth is that at the moment it is not “a profitable science”.

Do you consider yourself a disciple of any particular botanist?

Of course. And it is a source of pride to have great teachers. I have had two masters in my botanical life, Antonio de la Torre and Manuel B. Crespo. I have learned a lot from them, not only from their teachings, which have been and still are many because I am lucky enough to continue working with them, but also from their way of living botany.

Which botanist would you have liked to meet in person?

Humboldt, it is crystal clear to me. I like to think of those naturalists who enlisted on ships in search of a world of animals and plants to discover. I have that spirit and that is why I also admire Jeanne Baret; I do not know if it was love or botany that encouraged her to disguise herself as a man and enlist on a ship as the naturalist’s assistant, possibly both, but she finished all the botanical work and was recognised for it. She seems to me to be a brave woman, one of those who later become a point of reference for botanical women like me.