Botanist of the month: Felisa Puche

More than 40 years as a teacher. Just as many researching bryophytes. Felisa Puche is full professor in the department of Botany at the University of Valencia, curator of the herbarium of bryophytes VAL-Brióf at the same university, and has been part, among others, of the project Iberian Bryophytic Flora. She’s our botanist of the month.

What attracted you to botany?

When I started the degree, I felt more drawn towards animals, but after studying the subject of Cryptogamy during my 2nd year, I discovered a fascinating world: algae, fungi, but specially mosses and hepatics. Everything changes when you see it through a lens or a microscope. The knowledge of this world, unknown for me at the time, led me to write an undergraduate thesis, something between the current Undergraduate Degree Final Project and Master’s Degree Final Project. Understanding plants, their diversity and distribution were the main reasons why I felt attracted to a career in Botany.

Tell us a bit about your professional career

I studied the degree in Biological Sciences and PhD in the Universitat de València. I started working in the Botany Department at the Universitat de València not long after finishing my studies as a Practical Class Assistant, I held other positions and, since 1987, I’m full professor. I’ve taught many years the subjects of Botany and Biology, as well as subjects in PhD and master’s degrees.

My research activity has been focused on the study of bryophytes. I started in 1977 writing an undergraduate thesis about the bryoflora of Cedrillas (Teruel) in the Sierra de Gúdar. Later, I did my PhD dissertation (1983) on bryoflora in two mountain ranges of the Iberian System (Palomita and Penyagolosa mountains), and since then I studied, with different colleagues and interns, the bryoflora in the Valencian region, including the most important mountain ranges in the provinces of Castelló and València, and some in Alacant.

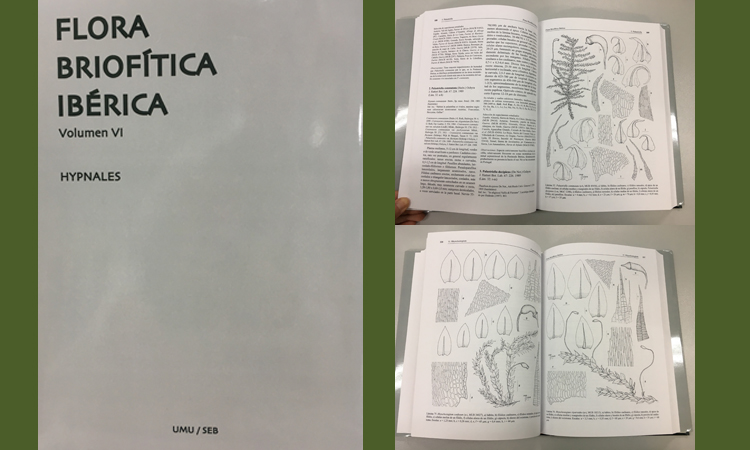

I also worked in the taxonomy of bryophytes and did the genera: Dicranella, Distichium, Ditrichum, Goniomitrium, Habrodon, Oedipodiella, Pleuridium, Pterigynandrum, Seligeria, Tortella and Trichodon for the publication of Iberian Bryophyte Flora, concluded in 2018. I participated as an author in the creation and publication of the world checklist of hornworts and liverworts. I’ve worked in bryophyte and Mediterranean shrubland (‘matoll’) biogeography and phylogeography, discovering new species in Europe, and I’ve also provided data for the creation of many distribution maps of bryophyte species in the Iberian Peninsula.

Since 2010, I’ve resumed my collaboration with Dr. J.G. Segarra Moragues. We’re currently working on the genus Riella. Particularly, on the taxonomy, biogeography, phylogeography and genetic variability of R. helicophylla, thanks to the funding granted by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

Another area I dedicated part of my research to is the conservation of bryophytes. We have put forward micro-reserves for the conservation of bryophytes of the Region of Valenica and we have collaborated in the ‘Atlas of threatened bryophytes in Spain’ I’ve recently taken part in the preparation of the IUCN Red List of European Bryophytes.

Finally, and parallel to all these years of research, I’ve initiated the bryophyte herbarium VAL-Briof. in the Universitat de València, which I curate. It currently has more than 11798 specimens, mainly from the Mediterranean area.

Which is the basic skill for your work?

Observation skills, I believe, is one of the fundamental abilities naturalists need.

Are you proud to have been involved in a particular project?

I’m especially proud to have been involved in the team of Iberian Bryophyte Flora, a project that started in 1998 with the goal of completing a flora of the mosses in the Iberian Peninsula. It’s a work in which all known species should be listed, with identification codes, descriptions of each one of them and an iconography based on good quality Iberian material. Although there were hardships, with dedication and time from the editors, coordinators and authors, the work was concluded last year and all 6 volumes have been published. Nowadays, it’s a reference book in worldwide bryology, it’s quality matches others like Flora of North America. Throughout the years of elaborating the flora, we Spanish bryologists forged a close and uninterrupted relationship, which allowed us to carry out the work. I’ll always remember those years.

What impact or effect does a project like this have?

Projects like this are highly valuable both scientifically and in the matter of natural heritage knowledge. From a scientific point of view, the Iberian material in primarily Iberian and European herbariums was examined. This allowed for removing errors, finding quotations and new species in the Peninsula, etc. Furthermore, we all learned how to make rigorous descriptions and keys, under the close supervision of the editor of each genus. For that reason, scientifically speaking, Iberian Bryophyte Flora entailed a progress in knowledge. In a social sense, flora is the natural heritage of a country, and its knowledge, communication and conservation start with a work like this, which became the reference work since it was first published.

This year marks the 15th anniversary of the Diccionari de Botànica (PUV, 2004), a work developed alongside Antoni Aguilella. What would you highlight about this dictionary?

I keep a fond memory of the process of developing the Diccionari de Botànica, although it was very arduous, partly, because of its double aspect: botany and philology. Every term was reviewed by the Linguistic Normalization Service of the University of Valencia. I think this resulted in a very useful book in both aspects, which is truly fulfilling.

You were a member of the first board of directors of the Spanish Bryological Society, and a former president. Could you tell us about this experience?

The Spanish Bryological Society was the result of the work and dreams of many bryologists who, led by Dr Creu Casas, thought that it could be useful for promoting the knowledge about bryology in Spain. It was an honour for me to be its president from 2005 to 2009. Besides, there was a special moment in 2007, during a Cryptogamy congress in León. The organization paid homage to Dr Casas, who had passed away a few months earlier, and I was entrusted, as president of the Society at the time, with collecting the small sculpture with a plaque in her memory and later handing it over to her family.

As you previously mentioned, you are responsible for the University of Valencia’s bryophyte herbarium. Why are these kinds of collections so important?

I started the University of Valencia’s bryophyte herbarium, VAL-Briof., in 1976, as a result of beginning my PhD dissertation, since I needed to maintain reference and comparable materials, and to deposit the sheets that certified the collection of plants in said studies. It’s currently placed in the Department of Botany and Geology of the Faculty of Biological Sciences, in the Burjassot-Paterna Campus.

Over its 43 years of history, the VAL-Briof. herbarium has gathered a significant collection of bryophytes that, nowadays, amounts to 11,798 sheets. Most of them, more than 80%, are mosses. The samples include material of more than 1,200 taxa. In the Herbarium VAL-Briof. there are four type specimens. Geographically speaking, the sheets kept in the herbarium are mostly from the Iberian Peninsula, mainly from the Valencian region. There’s also a great representation of foreign cities, from some regions of Chile and South Africa.

The oldest preserved specimens date back to more than a century and correspond to the bryological research started by the former dean of the Faculty of Biological Sciences and director of the Jardí Botànic, Francisco Beltrán Bigorra, who dedicated his first research years to Bryology. The fire in the Cabinet of Natural History of the University of Valencia, in 1932, damaged the Biology section and most of these collections were lost.

In the Herbarium VAL-Briof. there are 1,420 deposited sheets of the Briotheca Hispanica, an exsiccata that was initially prepared by Dr Creu Casas, the main pioneer of Bryology in Spain in the 20th century.

These kinds of collections make up reference materials of the diversity of these taxa. The herbarium material, if well preserved, can be used in anatomic-morphologic studies and the recent material can also be used for molecular studies.

What is your work like as the responsible for this collection?

My work consists of the collection, identification, preparation of the specimens and entering them in the database. The institution has not been considerate with the needs of fungi, lichen, algae and bryophyte collections, there isn’t enough supporting staff nor budget, which is why the curators of each collection have taken charge of this job, as well as preparing the shipment of lending material to researchers who request it.

And what is your relationship with the Jardí Botànic?

Throughout my career I’ve had very little connection with the Jardí Botànic besides the annual visits with students. Circumstances were never right for me to have a close link to it. However, it is a very special place which I deeply care about, since I have lived close to the Jardí my whole life. I keep fond memories of my childhood summers playing there with my brothers and cousins, as well as taking there the Botany practical classes during our 2nd year.

As a full professor at the University of Valencia, you’ve seen several generations attending your classes. What’s the most important thing as a teacher?

After 42 years of teaching, I’ve seen many generations of biologists. Students have been changing because society has been doing so, technology has changed our lives and we’ve switched from teaching classes with hand-drawn diagrams on the blackboard, to transparencies in an overhead projector, to computer presentations. Current systems allow for spreading great amounts of information, but it’s a rather passive learning, usually knowledge doesn’t outlive the exam. I think we should modify the teaching methodology and dedicate most of the on-site classes to practice or field hours: teachers are unreplaceable there. The most important thing as teachers is to transfer the methodology of our field of knowledge to students so that they can deal with issues related to this matter in the future. Teachers should realize that information is available online, and our job should be more than simply passing on processed information.

And how do you imagine future botanists?

I imagine them with more technology at their reach that will allow them to identify much faster and more accurately, and with much more available data, which will widen their research scope and, especially, make travelling and collecting plants a lot easier in areas of the Earth that we still have much to know and learn about.

Do you consider yourself a disciple of any particular botanist?

Yes, I consider myself a disciple of Dr Creu Casas, because she introduced me in the world of bryology, and I learned with her the fundamentals of the work of a bryologist/botanist: how to collect plants, where to find them, how to preserve the specimens, how to identify, which books to use, how to make excellent cuts by hand, how to prepare the sheets for the herbarium. I remember the numerous trips to Bellaterra, to the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, when I was doing my dissertation, to review the delicate material. When she was teaching a class, I headed to the herbarium (BCB) and spent hours looking at sheets of those species that I had only seen in the books. I also remember dearly the bryology meetings after field work, the night closing in, when we identified the collected specimens.

Which era of Botany would you have liked to live in and why?

I feel very lucky and I’m grateful to life, which has given me a wonderful family and a job that I love. I like this era that I got to live, the progress in many fields of biology has been formidable: having access to molecular techniques that allow us to find out the link between different populations of a species and being able to deduce species migration or colonization paths was unimaginable a few years ago. Climatic change will transform environmental conditions, which will in turn transform the flora and vegetation, we still have a lot of work to do.