A tour of the Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz de la Sierra

Jose Aparici invites us to travel to Bolivia, in particular to the Municipal Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. A green lung, as he calls it, that became the last stop in his cooperative adventure on the other side of the ocean. Palm trees, native fruit plants and other fantastical plants will join us in this tour, even a dancing orchid or the tree of the future will make an appearance.

One of the largest in South America, with more than 536 acres, and unique in its continent due to its division between gardens and relict forests, the Municipal Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz de la Sierra (located 5 miles away form the city) is the most active one in Bolivia. Home to several projects, it welcomes more than 150,000 visitors per year. My visit to the country’s metropolis and one of the jewels of the Bolivian East was the end of my technical cooperation program in Biology, Agronomy and Management of the Natural Environment, framed in the VII Municipal Volunteer Specialist Program 2018 of the Valencian Fund for Solidarity.

The Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz opened its doors more than 30 years ago. First located on the bank of river Piraí, west of the city, the great flood of 1983 forced its move to its current location, suggested by its former manager Noel Kempff Mercado. A very well known and respected Bolivian naturalist, Kempff was the main driving force of the 20th century for the conservation of nature in a country that occupies the top positions on a continental and global scale in terms of biodiversity, species richness and density, and ecoregions.

Rainbow waterfall at Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, northwest of the Santa Cruz Department and bordering with Brazil / Pattrön, flickr

Rainbow waterfall at Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, northwest of the Santa Cruz Department and bordering with Brazil / Pattrön, flickr

In 1986, Kempff was murdered by drug traffickers while he was on an expedition to the Caparuch mountains, currently the National Park named after him. His murder shocked the Bolivians and was a turning point in the social war against drug trafficking. The light aircraft in which the research team was travelling landed by mistake on a runway used by a drug factory hidden in the middle of the jungle. In fact, older readers will remember the news about Spanish scientist Vicent Castelló, the only survivor of the accident who was able to dodge the bullets, escape and hide in the green thick jungle until he was rescued a few hours later.

Nowadays, the Garden’s 536 acres are divided in two areas of great floral and forestry diversity: the conservation area and the enrichment area. The first one takes up to 90% of the total surface and is home to the three most representative forests of the Department of Santa Cruz: the subtropical forest, the chiquitano forest and the chaqueño forest. All three, each one in a different state of conservation, are unique. Their peculiar floristic composition is distinctive from their counterpart forests located in other nearby national parks. In the enrichment area, we can find the gardens with eco-trails, the plant nursery, the herbarium, the labs, the palm grove, the cactarium and the orchidarium. In recent years, the improvement of their environments and the diversification of the activities open to the public, consisting of different events throughout the year, have increased the number of visitors, who are becoming attracted to visit natural areas without having to travel far from the city.

Discovering the collections

From the moment we enter the Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz, it doesn’t matter where we are looking, we as visitors are in direct contact with nature. And there are many curious facts waiting to be discovered! At the beginning of the tour, we can see the Palmatarium, a space full of different species of palm trees from the Department and other Bolivian regions. There are 30 species in total.

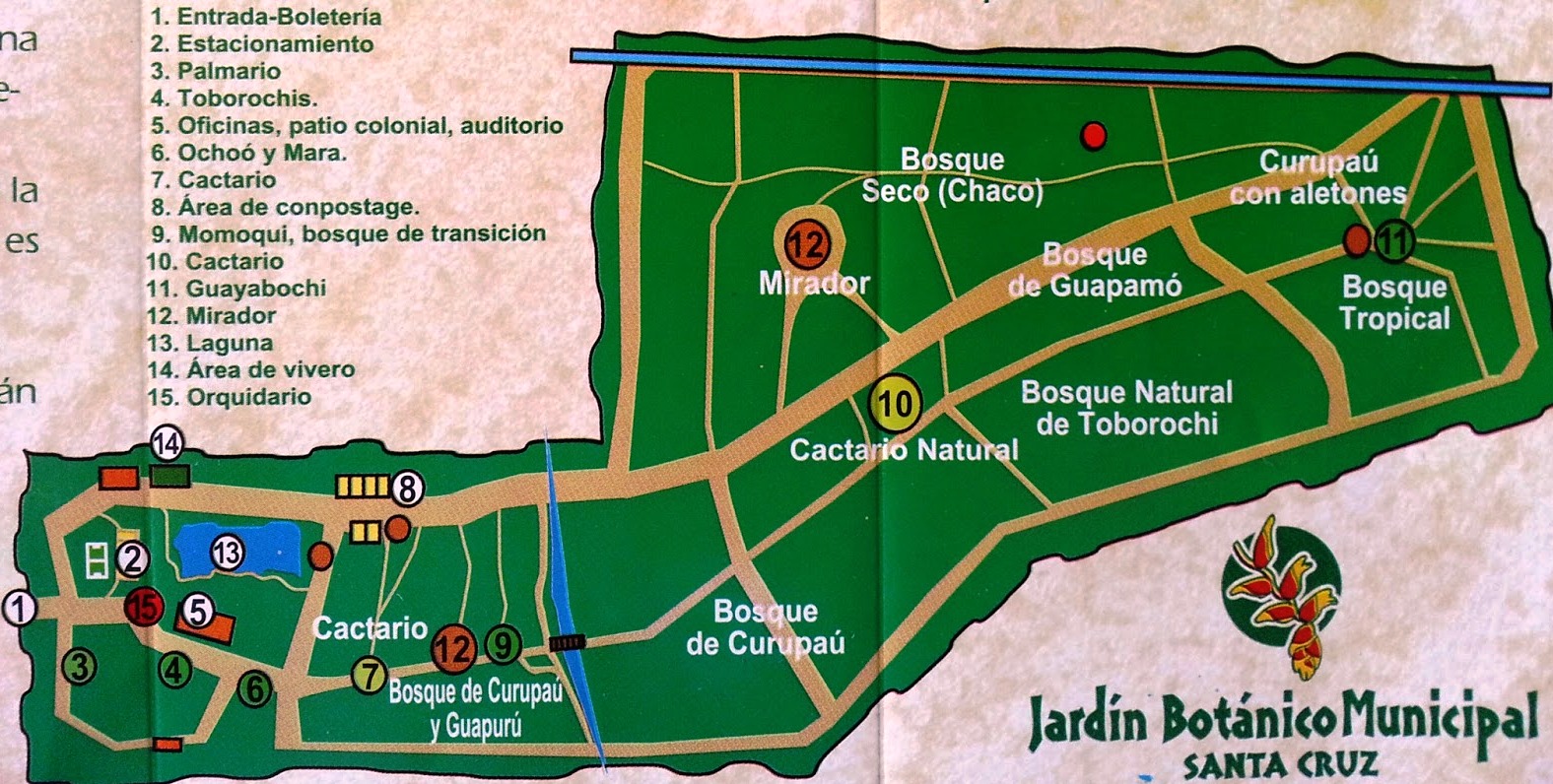

Map of the Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. The stream we sea separates both areas: the enrichment area (exhibition, recreational and working areas) and the conservation area (forests) / Jose Aparici

Map of the Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. The stream we sea separates both areas: the enrichment area (exhibition, recreational and working areas) and the conservation area (forests) / Jose Aparici

If we follow the marked paths, we will embark ourselves on a learning journey along which we will find collections of tajibos (of the genus Tabebuia), sixty types of chorisias, bromelias, cacti, desert roses and native fruit plants like the jabuticaba, the guapomó, the cupesí (similar to the carob) and the achachairú, among others. In fact, each space dedicated to a specific collection has the corresponding signs were we can find all the info about the species and the number of specimens owned by the Botanical Garden.

Each of the species included in the collections has been selected according to its restricted distribution, its rarity, its degree of vulnerability or its level of endangerment. Most of them were brought back from collection trips. It is the case of the “Yellow Roosters” from Samaipata. Pertaining to the Heliconiaceae family, there are a dozen at the Botanical Garden. In fact, when it comes to the sixty different species of cactus, the endemic ones are the main subject in the investigation and propagation programs developed by the Botanical Garden.

El jabuticaba (Myrciaria cauliflora) s a small tree native to Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia, especially distributed in dry or sub-humid areas of the Department of Santa Cruz. The fruit, located near the tortuous ramifications, is very popular. It is commonly used to make sweets and liquors, and it also has many medicinal properties. / Jose Aparici

El jabuticaba (Myrciaria cauliflora) s a small tree native to Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia, especially distributed in dry or sub-humid areas of the Department of Santa Cruz. The fruit, located near the tortuous ramifications, is very popular. It is commonly used to make sweets and liquors, and it also has many medicinal properties. / Jose Aparici

The Botanical Garden keeps a record of all the plants living in its premises. One of the most famous attractions is the herbarium, which performs research and conservation tasks through dry samples belonging to the flora of the region. It has 18,000 samples perfectly classified in a unique and modern archive, where plants and their parts, such as leaves, stems or fruits, are safeguarded from extinction. A particular birth certificate of each plant that helps to verify its existence, know its location and be aware of the state of the plant and its characteristics of reproduction. All this logistical framework is aimed at raising awareness among the population about the fundamental conservation of forests through understanding and recreation, bringing the people closer to nature and all its forms of expression.

In recent years, the increase of drought periods in the region has forced the Botanical Garden to minimise this climatic situation through strict care accompanied by the installation of a modern automatic irrigation system that constantly provides a fairly humid environment, especially during low temperatures at night. In addition to improving the gardens and the collections of living plants, it is necessary to provide the public with a more agreeable and attractive space where recreational activities can be held.

From the in vitro lab to the orchidarium, the heartbeat of the Garden

Kempff Mercado’s dream of turning the Botanical Garden into a space for the conservation and exhibition of the floristic and forest diversity of the Department of Santa Cruz has become a reality. Among the collections, orchids occupy a privileged place, intermingled with ferns in an orchid garden that takes lovers of these complex flowers to a majestic natural landscape surrounded by colours, streams and even a waterfall.

SBeing the most visited and photographed place in the Botanical Garden, the orchidarium has an interior route interspersed by aqueducts, bridges, streams and waterfalls that, together with the collections, makes it an oasis. Plus, there is always a guide available to answer any question about taxonomy. / Jose Aparici

SBeing the most visited and photographed place in the Botanical Garden, the orchidarium has an interior route interspersed by aqueducts, bridges, streams and waterfalls that, together with the collections, makes it an oasis. Plus, there is always a guide available to answer any question about taxonomy. / Jose Aparici

When searching among the wide diversity of specimens, we can find an orchid commonly known as the dancing orchid. Unique on our planet it is, nowadays, endangered. Historical data show the dancing orchid was discovered by biologist René Moreno Suárez in the valleys of Santa Cruz more than four decades ago. A couple of years later, the flower fell in the hands of North American scientists in order to study and classify it until it was assigned a scientific name: Oncidium stacyi Garay. They never even considered naming it using elements from its place of origin or even acknowledged the local naturalists who discovered it!

Under the slogan “the flower, a common cause”, the dancing orchid was declared the symbol of the celebrations of the Bicentennial and the 450th anniversary of the founding of Santa Cruz de la Sierra by the local administration. The conservation of the orchid was considered an essential part of the city’s cultural heritage and the starting point for the creation of the plant biotechnology lab.

In vitro orchid incubation room with a photoperiod and controlled temperature in the Garden’s plant conservation laboratories. It takes about 5-6 weeks to appreciate a green carpet in the glass. After 12-18 months, the seedlings are carefully extracted. The culture medium, the utensils and the seeds are subjected to a strict sterilisation process under aseptic conditions. / Jose Aparici

In vitro orchid incubation room with a photoperiod and controlled temperature in the Garden’s plant conservation laboratories. It takes about 5-6 weeks to appreciate a green carpet in the glass. After 12-18 months, the seedlings are carefully extracted. The culture medium, the utensils and the seeds are subjected to a strict sterilisation process under aseptic conditions. / Jose Aparici

More than 10,000 specimens of hybrid and native orchid species are cultivated and subjected to in vitro reproduction systems in this lab, since after their growth and acclimatisation, reintroduction programs are implemented to return them to their natural habitat. Some 500 orchids have already been cultivated in this enclosure or beyond this family, and the laboratory produces approximately one thousand plants each year to beautify the place.

Enjoying nature: visiting three forests in one day

The chiquitano, subtropical and chaqueño forests are the three major ecosystems that converge in the Botanical Garden, bathed by the Guapilo stream, a burst of beauty and floral richness that embraces us. This environment makes us feel small when we let ourselves be carried along a 4 miles ecological trail, interspersed with interpretive stops, rest stops and detours. A sea of tree canopies surrounded by what looks like an island, a very high lookout tower at one of the trail stops that allows us to appreciate panoramic views of the rest of the Botanical Garden and the skyline of the metropolis of Santa Cruz. But having said that, what are the chiquitano or chaqueño forests like?

Section of the Garden’s eco didactic trail located in the enrichment zone, near the first viewpoint. The path belonging to the wooded area (conservation zone) is restricted to guided motorised tours due to the high presence of snakes. / Jose Aparici

Section of the Garden’s eco didactic trail located in the enrichment zone, near the first viewpoint. The path belonging to the wooded area (conservation zone) is restricted to guided motorised tours due to the high presence of snakes. / Jose Aparici

In the undulating lowlands of eastern Bolivia, specifically in different provinces in the centre and east of the Department of Santa Cruz, we find the Chiquitana ecoregion, composed of the largest dry tropical forests on the planet and characterised by its transitional location between the humid climate of the Amazon and the semi-dry climate of the Gran Chaco. Chiquitano vegetation ranges from semi-deciduous to deciduous plants, and more than 75% of the forest’s species have commercial value. Species exclusive to the ecoregion include the Machaerium scleroxylon, the Caesalpinia pluviosa, the Centrolobium microchaeta and the South American oak Amburana cearensis, among others.

The Chaco ecoregion, in the southeast of the Department of Santa Cruz is part of the Boreal Chaco and includes dry savannas and thorny scrublands. We can find numerous succulent plants, xerophytic plants and a floristic composition very marked by the edaphic and topographic conditions, since the landscape is formed by undulating plains, hills and isolated mountain ranges with sandy to loamy soils. Cacti such as the carahuata or sipoi, and trees such as the cupesi (white carob tree), cupesicho (black carob tree), toboroche, quebracho, or guayacan, among various types of palms and shrubs such as the mistol or tusca, all of them popular names in the area, stand out in this area.

We must take into account that, after the 6-8 months of the in vitro, the growth of the in vitro specimens, such as those of Paulownia tomentosa, is prolonged for two more years before they are ready for repopulation / Dai Rui, flickr

We must take into account that, after the 6-8 months of the in vitro, the growth of the in vitro specimens, such as those of Paulownia tomentosa, is prolonged for two more years before they are ready for repopulation / Dai Rui, flickr

Speaking of forests, the tree of the future is grown in Santa Cruz and the first seedlings have been produced experimentally by in vitro technique in the laboratory of the Botanical Garden. We are talking about the Paulownia tomentosa or Kiri, its popular name, belonging to the Paulowniaceae family. Originally from China, this Empress tree has generated great expectation on a global scale because of its exceptional qualities such as its giant roots, that allow the recovery of eroded land, the absorption of up to 10 times more carbon dioxide than other forest plants or the fact that in a period of five years can get to a height like that of an oak of 40. It can grow up to 27 metres high, with trunks between 7 and 20 metres in diameter and large leaves 40 cm wide. The Kiri is the jewel of the conservation program and subsequent afforestation of around 70 endangered tree species that are accommodated in suitable physical and chemical condition.

The Botanical Garden in numbers

2015 was a turning point year for the Garden of Santa Cruz. In just one year, the number of visitors went from the usual 3,000 to more than 100,000. A vertiginous ascent thanks to the millionaire investment in infrastructure made by the municipal government. In particular, in 2016 there were 101,600 visitors, 104,600 more than the previous year.

Local students visiting the Garden / ©Jardí Botànic Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, facebook

Local students visiting the Garden / ©Jardí Botànic Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, facebook

Students from schools, high schools and universities of the city and the province are the main visitors. Together with academics, families and groups of friends make the profile of the regular visitors that the Botanical Garden receives annually. The Botanical Garden is a living classroom where we can touch and smell what we only see in books. An emblematic corner for those sectors of the population who want to forget the hustle and bustle of the city without going far away from it and be in contact with nature for a few hours. However, it is actually a strategic mix of factors that have created the Garden’s formula for success.

In the first place, the existence of an environmental education office responsible for the annual promotion of an agenda consisting of training sessions and guided tours that have helped to increase the public’s interest. During the winter and summer holidays, recreational activities are held during the school break: documentary screenings, workshops, ecological games, and camps on the weekends, among others. In addition, there is already a tradition of organising four important fairs, among others: the Orchid Festival (March), the Succulent Plants Festival (May), the Desert Rose Festival (August) and the Bonsai Festival (October). These shows bring together hundreds of collectors from all over the country and attract thousands of visitors during exhibition days.

6th National Bonsai Fair at the Municipal Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz / El Deber

6th National Bonsai Fair at the Municipal Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz / El Deber  The Panoramic Viewpoint rises 18 metres off the ground to provide a sweeping view of the surrounding area / ©Jardín Botánico Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, La Región

The Panoramic Viewpoint rises 18 metres off the ground to provide a sweeping view of the surrounding area / ©Jardín Botánico Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, La Región

In the second place, technical facilities (such as laboratories, the herbarium, the orchid garden, the palm grove or the cactarium) that are complemented by new areas and tourist attractions, thus facilitating greater comfort and options for the visitors to enjoy the natural space. There is also a wooded area with a network of trails, a lookout point located on the inner area, and a nursery and organic garden with a wide variety of forest, fruit and ornamental plants, plus phytosanitary products for sale. In addition, we can find the Natura classroom and its ten specialised guides to accompany groups of students or delegations, an auditorium with capacity for a hundred users, a 1.5 hectare lagoon with a waterfall, floating dock and viewing balconies, and a colonial patio, a children’s playground, a camping area for overnight stays, a picnic area equipped with furniture, a dining room for institutional or private events and a parking area for 250 vehicles. According to its manager, these dynamic spaces should be always changing in order to keep entertaining the visitor. All these makes me ask myself: is the recreational, leisure role of the Garden fundamental? Would it vulgarise the Garden in the future?

A faunistic radiation is gaining space

The botanical focus of the Garden is perhaps not compatible with the high diversity of wildlife. In the wooded areas, we can observe a great variety of animals such as primates, sloths, squirrels and an explosion of migratory birds that use the Botanical Garden as a refuge for resting and feeding. More than 270 species of birds that position the Botanical Garden as one of the places with more diversity inventoried in the province of Santa Cruz. Moreover, there are 300 species of diurnal butterflies and about fifty species of coprophagous beetles, one of which was discovered for the first time in the Garden. The latter are particularly vulnerable because of their direct relationship with mammals and birds, and the increased colonisation of other invasive and exotic species.

A sloth and its cub at the Botanical Garden / ©Jardín Botánico Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, La Región

A sloth and its cub at the Botanical Garden / ©Jardín Botánico Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, La Región

This scenario deepens the distinction of two kinds of public: one interested in the Garden as a zoological space and the other as a botanical space, thus generating an unwanted pressure on the Garden itself, where the value of plant conservation research and environmental education should be prioritised while restricting the recreational activities. In fact, some reports have addressed whether the Garden should really aspire to become a Bioparc, which may irreversibly affect the ecology of the biota and the interactions of the existing native fauna before the incorporation of new ones.

Forest mantle of the Botanical Garden and part of the industrial peri-urban rings of the metropolis of Santa Cruz, outlined on the horizon of a panoramic view taken from the lookout tower / Jose Aparici

Forest mantle of the Botanical Garden and part of the industrial peri-urban rings of the metropolis of Santa Cruz, outlined on the horizon of a panoramic view taken from the lookout tower / Jose Aparici

Nowadays, the project has been paralysed, but in 2015 there was a plan to build a hypothetical Bioparc on the las chaqueño forest of the Garden. Many voices raised warning that the alteration of this forest would represent a loss, an irreversible impact for Santa Cruz and for Bolivia. Since the aforementioned ecosystem is unique, relict and characteristic in a peri-urban area, it would degrade the city, and it would seriously hinder new generations from learning about the original native vegetation that once covered the Santa Cruz plain. Considering the Botanical Garden as a possible location for a new zoo underestimates the local values of both flora and fauna, including species of great conservation value, as well as the scientific, educational, environmental, cultural and historical values shown to society.

Strengthening the ecological value of the Botanical Garden

The Botanical Garden of Santa Cruz has been designed to be an ecological reference, a living classroom where students reinforce everything they have learned in school, within the field of botany or zoology. Therefore, the management continues to expand both the plant collections and the construction of new greenhouses. The importance of the Garden is indisputable if we talk about species protection, as a refuge for migratory birds and, of course, as a vast forest territory with a regulating role of the local climate and wind control, among other factors.

Panoramic view of the Botanical Garden / ©Jardí Botànic Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, facebook

Panoramic view of the Botanical Garden / ©Jardí Botànic Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, facebook

The need to preserve the relict forests represented in the Garden is to be included in a protected natural area of municipal scope, with the legislative restriction of activities that could harm the natural values present and incentives to improve the state of conservation. The forests of the Garden are of high scientific value because of the records and descriptions of at least two species and a new genus in Bolivia, and because of all the pending research to be carried out to deepen the knowledge of the eco functions and dynamics of vegetation succession, as well as the influence of physical and chemical edaphic parameters on the functioning of the native ecosystems of Santa Cruz. This framework implies an extraordinary value as an area of study for future students of Biology, Agricultural Engineering or Forestry.

Bolivia’s natural forests cover an area of more than 133 million acres, representing 48% of the country’s surface, concentrated in the northern and eastern portion (Departments of Santa Cruz, Beni, La Paz and Pando) and 10% of the tropical forests in South America. This 48% of forest potential is composed of six different types of forests.

A family enjoying the forests of the Botanical Garden / ©Jardí Botànic Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, facebook

A family enjoying the forests of the Botanical Garden / ©Jardí Botànic Municipal de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, facebook

Along with the sub-humid forest of Chiquitania and the arid forest of the Gran Chaco, we find the lowlands evergreen forest, an extensive formation that occupies the Amazon region of Bolivia, characterised by high rainfall. There is also the Yungas forest located in the humid valleys of the Andes Mountains, in the Department of Cochabamba and La Paz, a subtropical humid forest and he most commercially important zone since it contains a diverse forest with more than a hundred species used in the timber industry, and the mountainous humid forest that extends to the south up to 2000 m. of altitude and is considered less productive. All these natural treasures must be protected, conserved and promoted. This is the reason why the Botanical Garden has to remain active and on the right path of its scientific vocation.