Adanson, the forgotten discoverer of baobab

Michel Adanson was a renowned botanist in the 18th century who discovered many scientific treasures in Senegal, among which is the emblematic baobab. In Espores we invite you to embark on his thrilling botanical adventure: from the herbaria that preserve his findings to the valuable connections he built with other scientists from his time, like Cavanilles. By the hand of Leopoldo Medina and Carlos Aedo, from the Jardín Botánico of Madrid, CSIC, we’ll go on a journey throughout the history of botany that will bring us closer to a figure as fascinating as often overlooked.

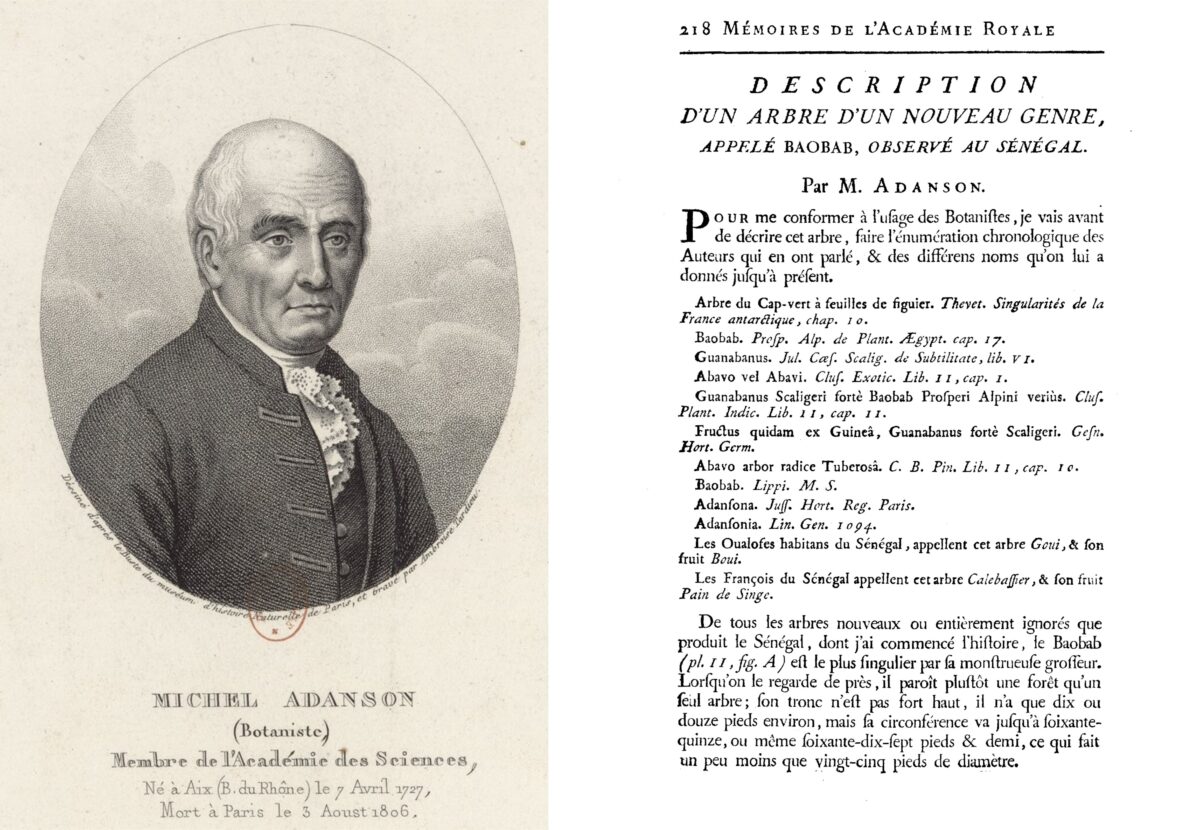

His name might not sound familiar, but Michel Adanson was the first western explorer to get to the area of Senegal, and he identified many undescribed species, including baobab. To walk through his life means not only highlighting his many contributions to botany, but also understanding a bit better the rivalries that exist in the scientific community, regardless of the historic period, and following the trail of all the material he collected on his journeys all the way to our country, in the herbarium of the Real Jardín Botánico of Madrid.

Today we’d like to trace out a route from Michel Adanson (1727-1806) to the Valencian scientist Antonio José Cavanilles (1745-1804), and we’d like to do it through their herbaria. The herbarium of Cavanilles is probably the most valuable collection of all those kept in the Real Jardín Botánico of Madrid, where he was the director between 1801 and 1804 after his education in the Jardin Royal (later named Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle) between 1781 and 1789. The value of this collection, notably rich in type material of new species that he described, is reinforced thanks to the specimens he gathered from various important botanists of his time linked to that museum, including the protagonist of this story, Adanson.

Adanson and his African journey

Adanson was born in the small Provençal city of Aix, in southern France. His family moved to Paris around 1740, where he continued his classical studies and got interested in natural history education taught in Jardin Royal and Collège Royal. He was a pupil of the physician and botanist Bernard de Jussieu (1699-1777), among others, and he started around this time to create a personal herbarium with the plants he collected during the trips organized by the Jussieu brothers in the surroundings of Paris.

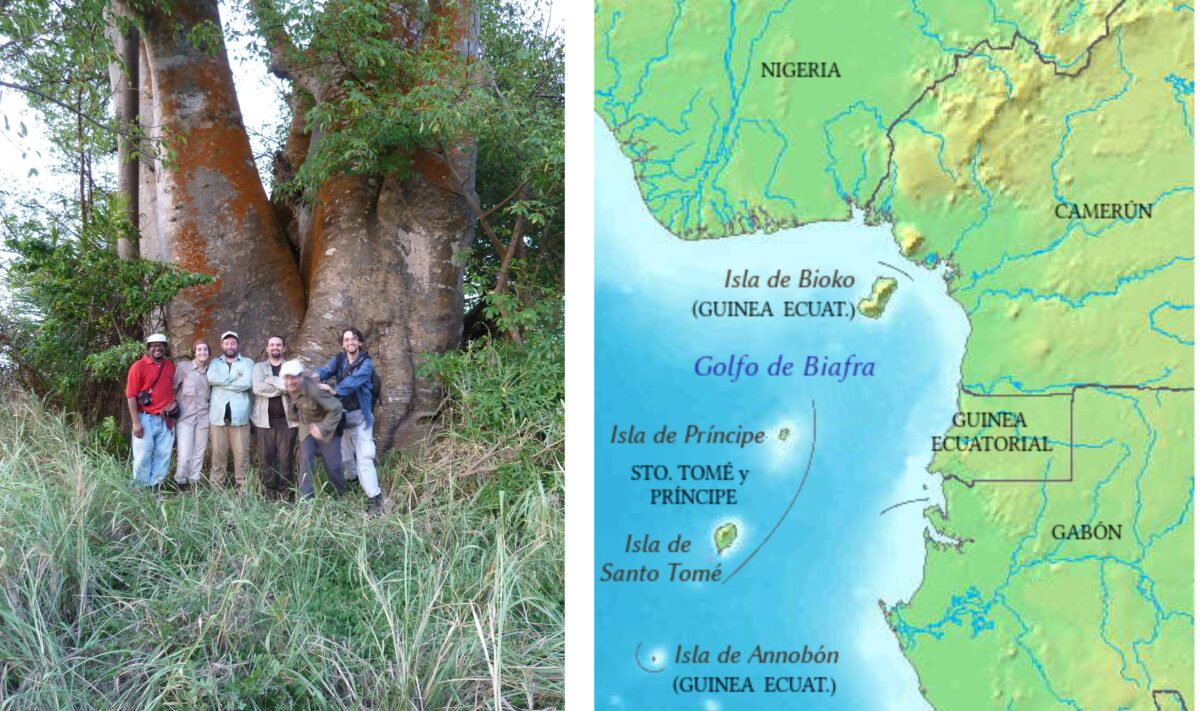

Thanks to his family connections, Adanson managed to get himself sent to Senegal by the Compagnie des Indes, where he devoted himself to the study of nature in a broad sense, since he was focused on plants, animals and minerals. He sailed off from Lorient, Brettany, on the 3rd of March 1749. He wouldn’t be back to France until the 4th of January 1754. As the first western explorer in those African tropical regions, he discovered many new species, which he collected and sent to Europe for later study.

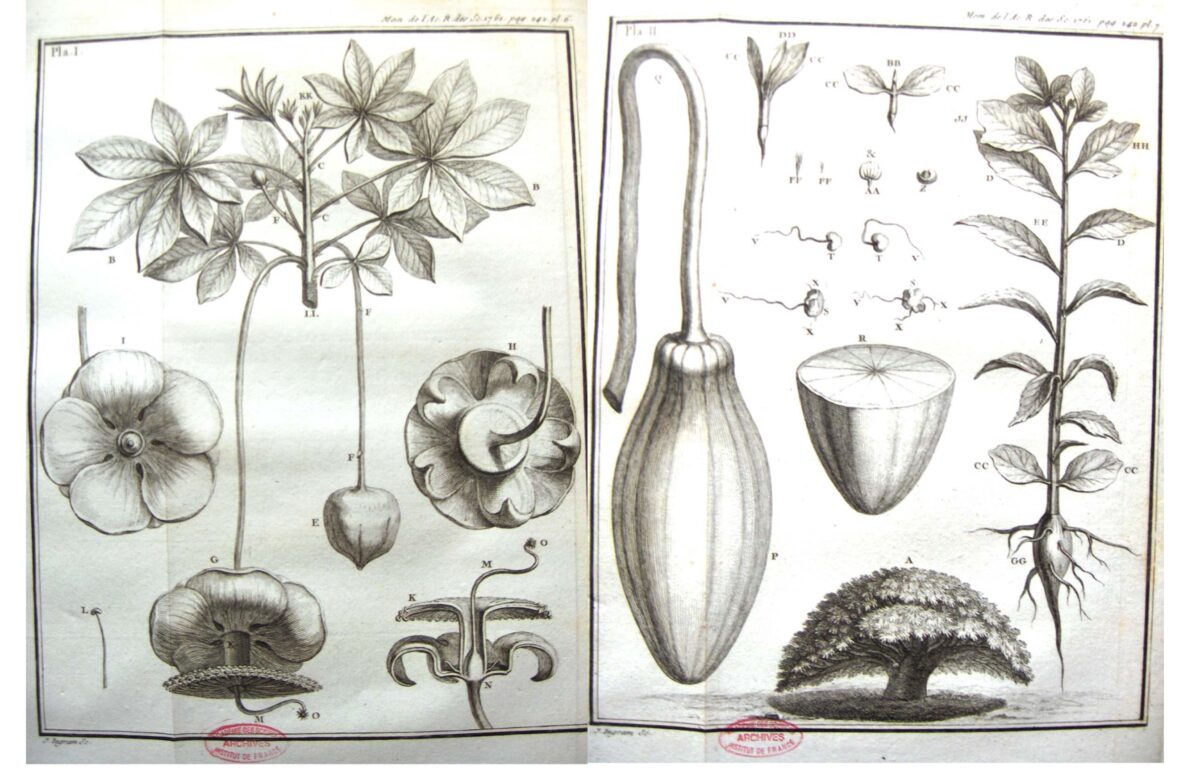

One of the most outstanding ones was baobab, a native species of sub-Saharan semiarid areas, which had been previously mentioned in Renaissance literature. These colossal trees, with truly spectacular bottle-shaped trunks, have blown away every traveller and have been the source of myths and legends in the local cultures. Adanson was impressed by this giant as well, and he wrote to Bernard de Jussieu in Paris to inform him and to send him a description, asking for it to be forwarded to Linnaeus, who was then working on his Species Plantarum.

In his correspondence with Linnaeus, Bernard de Jussieu already called the tree Adansonia, and he wasted no time and published the species as Adansonia digitata in his 1753 and 1759 works. Meanwhile Adanson, who had already returned from Senegal, wrote to Linnaeus in 1756, sending him a copy of a detailed description of the plant, which he had also sent for its publication in Mémoires de l’Académie Royale, with Baobab as the generic name. This publication, which was significantly delayed and did not come to light until 1763, came too late for the name proposed by Adanson to be accepted. The role that Linnaeus played here doesn’t seem quite elegant, since he took the scientific credit for the description of the plant by stealing it from its discoverer. To his credit, however, he was kind enough to dedicate Adanson the genus, a sentimental rather than scientific recognition, but not an inconsiderable one because it highlights his role as the finder.

New classification needs

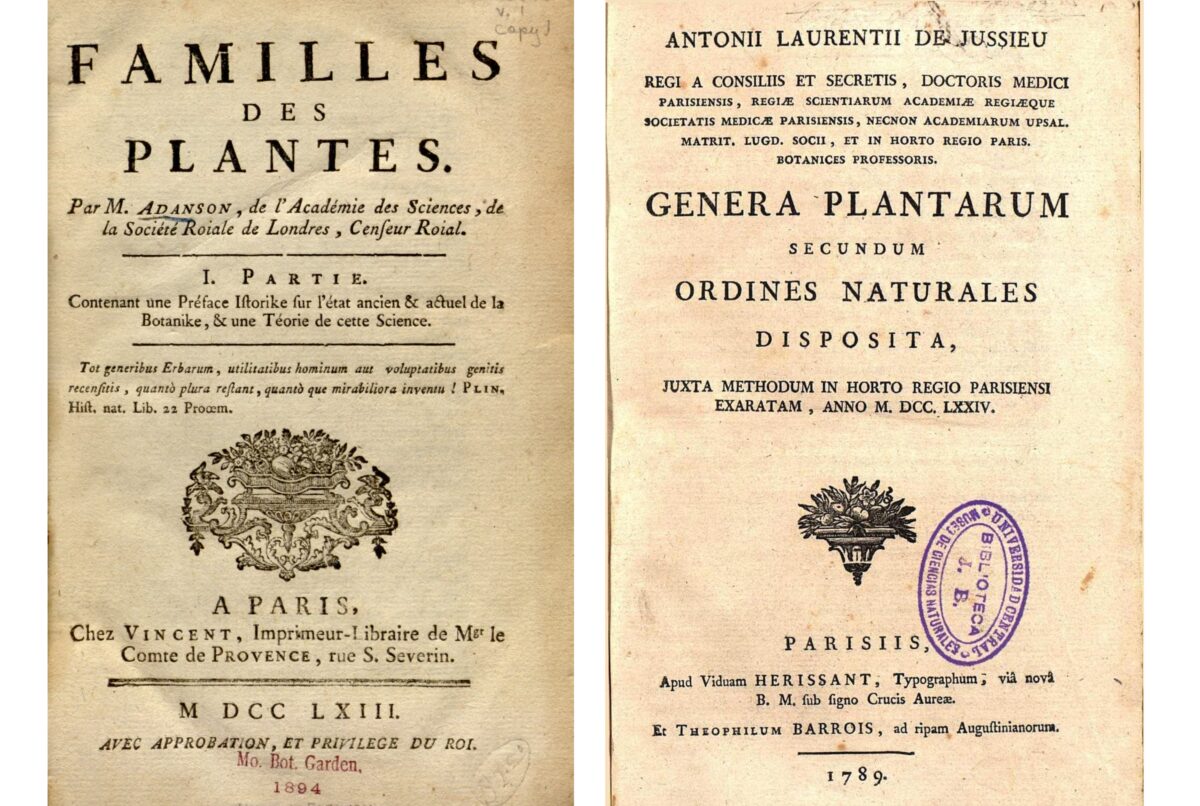

His stay in Senegal opened the doors of a new world for Adanson, the tropic, with plenty of new species that were completely different to the European ones, that did not fit in the plant classification systems that had been proposed by different authors to that point. This convinced him of the need to find a universal method that could rationally classify new species. There were two classification systems that fought to prevail at the time: Tournefort’s system, based primarily on the shape of the corolla, and Linnaeus’ system, based on the number of stamens. They were both considered artificial systems, very handy for the identification of plants, but seriously deficient when it came to classifying the species by their affinities. In response to this issue, Adanson published in 1763-1764 Familles des plantes, a book containing two significant contributions. On one hand, he revisited and elaborated on the idea of Pierre Magnol (1638-1715), professor at the University of Montpellier, of regrouping the genus into families. We owe Adanson many of the names and divisions of families that we use nowadays.

On the other hand, he established a classification method that takes into account every possible trait, which he named “natural method”, as opposed to the artificial systems we previously mentioned. His mentor, Bernard de Jussieu, had simultaneously developed a similar method to classify the plants of the Gardens of the Grand Trianon in Versailles that he never published. Adanson followed an inductive method, based on cartesian philosophy, which attached different degrees of importance to the traits a posteriori and depending on the considered group, while B. de Jussieu used a deductive method, in which he proposed a priori the importance of traits for the whole plant kingdom. Quoting Antonie Stafleu, Adanson “…was the first author that offered a logical basis for a natural classification of plants”.

The work of Adanson didn’t have much impact in his time, but it can be considered the starting point of modern classification systems, that over time would be reaffirmed by evolutionary ideas. 25 years later, Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836) published his Genera Plantarum (1789), in which he reflected his uncle Bernard’s ideas and proposed the distribution of plants into a hundred Ordines naturales, which would be the equivalent of Adanson’s families. Between the nephew and Adanson there was a rivalry that most certainly influenced the lack of credit that A.-L. de Jussieu gave to the contributions of our protagonist, whose results were, to a great extent, similar.

The outcome of Adanson’s work has received, also in this case, a symbolic rather than effective recognition. The International Code of Botanical Nomenclature establishes Genera plantarum of A.-L. de Jussieu as the starting point for suprageneric names of vascular plants, which means previous names are not considered. This arbitrary and hardly justified decision leads to 33 names of families being currently attributed to A.L. de Jussieu, even though they had already been published by Adanson.

A history of herbaria

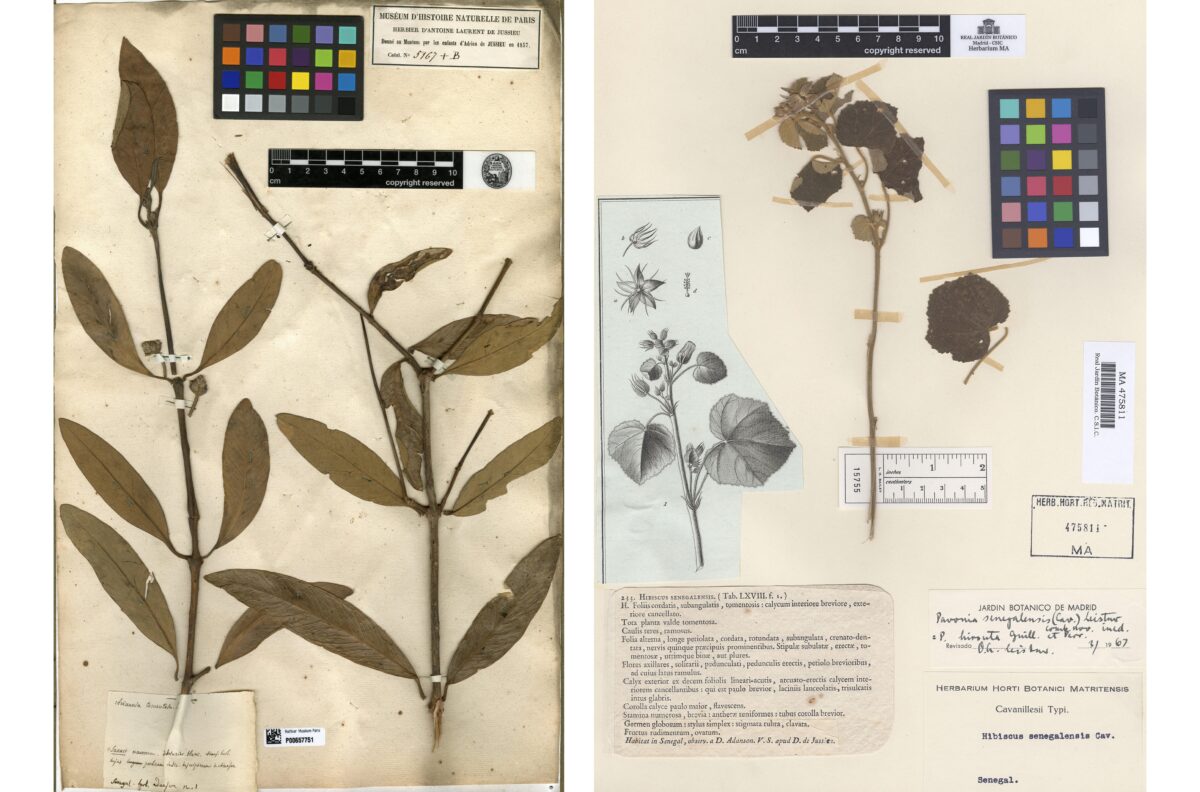

The plants of Senegal are without a doubt the most scientifically relevant out of all the plants that Adanson collected. During this expedition, he also made some collections when he stopped in Tenerife on his outward journey, and in the Fayal Island in the Azores on his return. The first set of duplicates of these plants, around 500 specimens, was acquired by the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle of París, while Adanson still lived, and was merged with the general herbarium of the institution. Other materials from Senegal are included in Lamarck’s and the Jussieu’s herbaria, nowadays preserved in said museum as separate herbaria.

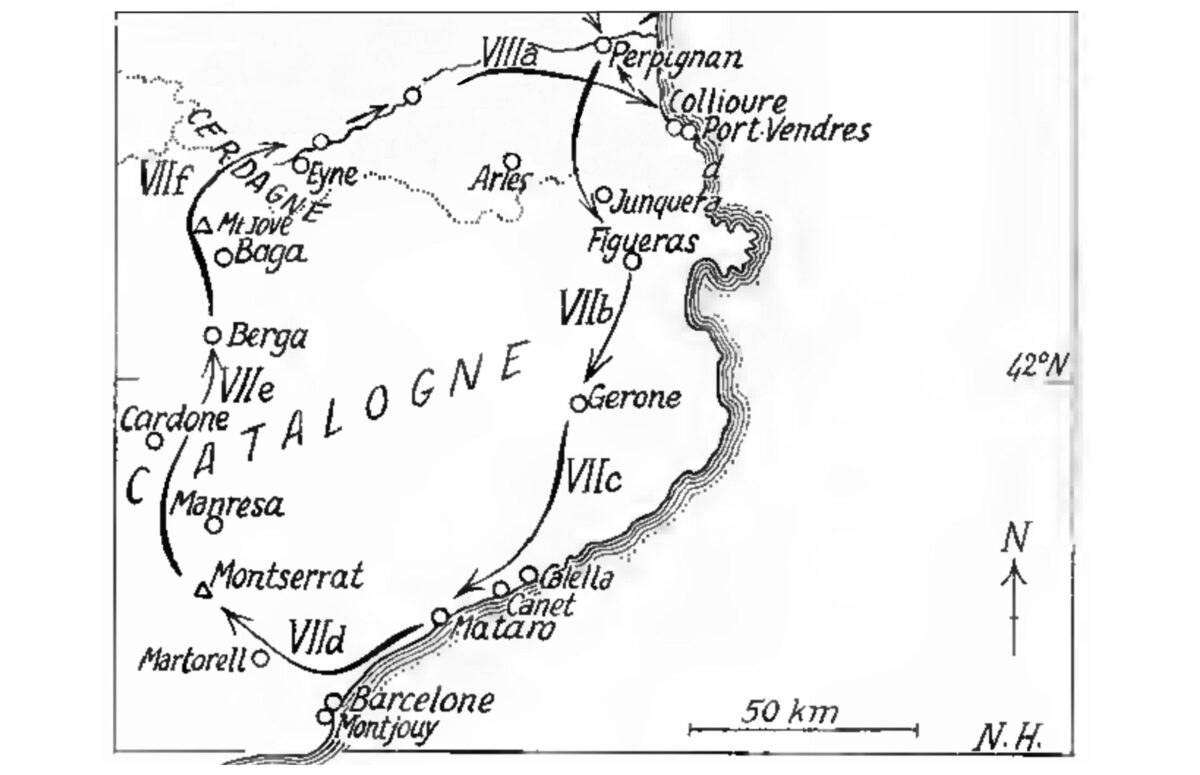

Adanson also had a personal herbarium of considerable size, with 24,095 specimens, in which he gathered his own collections and others from his correspondents. In France, he herborized primarily in Normandy and the surroundings of Paris, before and after his African journey. Between May and October 1779, he fled Paris to go on another journey of plant collection, this time to the French Midi, travelling across Auvergne, the Dauphiné, Provence and Pyrénées-Orientales, as well as some areas close to Switzerland and Italy. Regarding Spain, he got to the border on the 5th of July 1779 and continued his journey towards La Jonquera, Figueres, Girona and Barcelona. He returned via Montserrat, Berga and Cerdanya, arriving to the French side after 2 weeks. This personal herbarium, which mainly included European collections, his own and of his correspondents, added to the ones from Senegal, was passed on to his heirs, who preserved it well in the château de Balaine (near Villeneuve-sur-Allier), until 1924, when it was sold to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle of Paris, and it was integrated into its collections as a separate herbarium.

In the herbarium of the Real Jardín Botánico of Madrid, five specimens have been identified as collected by Adanson in Senegal, from family Jusseau’s herbarium, fragments that Cavanilles received as gifts during his stay in France. Another specimen of the same origin has also been preserved, coming from the seeds that Cavanilles planted in the garden of the Duke of the Infantado, since he was the preceptor of his children. Surely, the great reputation that Cavanilles had earned helped him get samples of various expeditions provided by his French colleagues. These specimens are of a great scientific value, given they are, in many cases, nomenclatural types of species proposed by Cavanilles. Besides, they have undeniable historical value because they show the relationships established between European scientists around this Parisian museum, which was at the time the most important centre of study of every discipline of natural history in the world.

The fate of Adanson’s work, which has been underestimated for too long, reminds us that scientific activity is not immune to the rivalry and meanness inherent to any human activity. But luckily, and in general, time and the right perspective end up inevitably attributing the scientific achievements to their rightful doers. We can now look back on Adanson’s work with a better understanding of his trajectory and imagine his incredibly interesting journeys by tracing his legacy in those botanical libraries called herbaria.